In colonial America, something as simple as a bed or spoon divided the haves from the have-nots

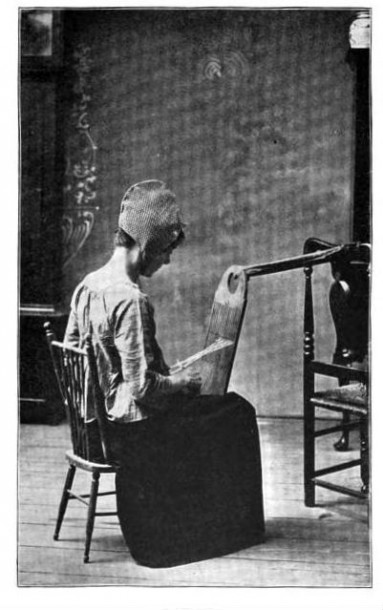

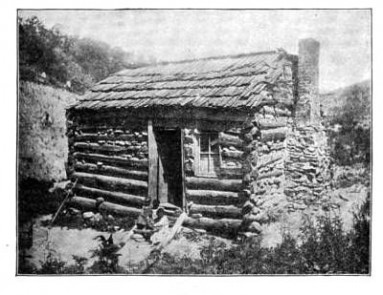

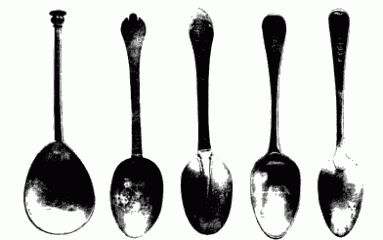

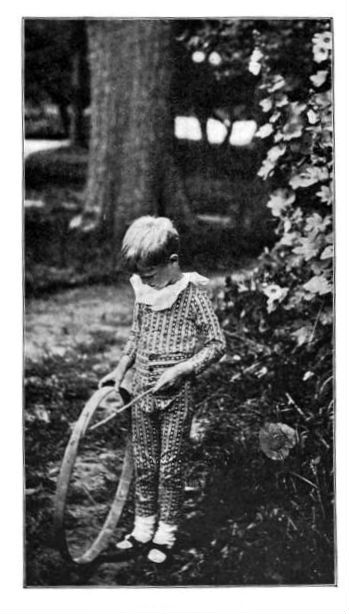

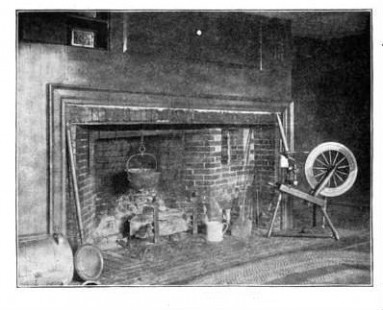

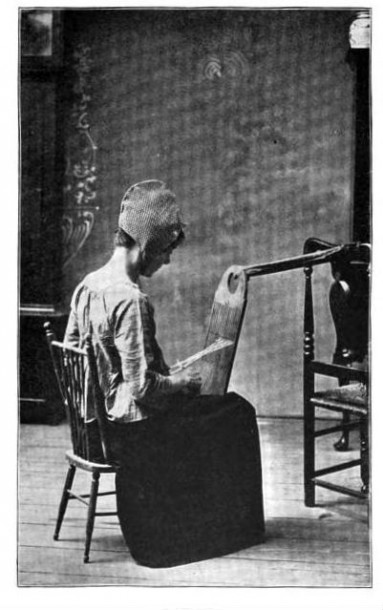

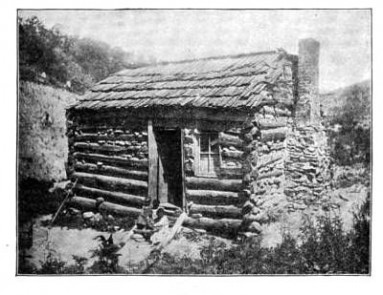

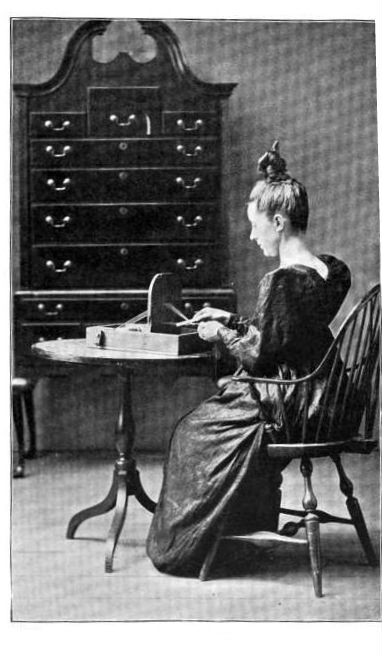

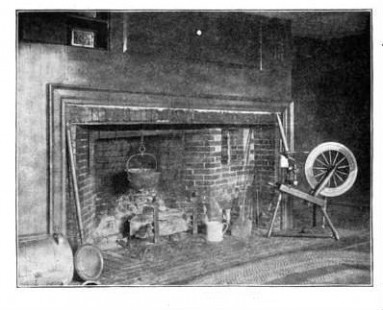

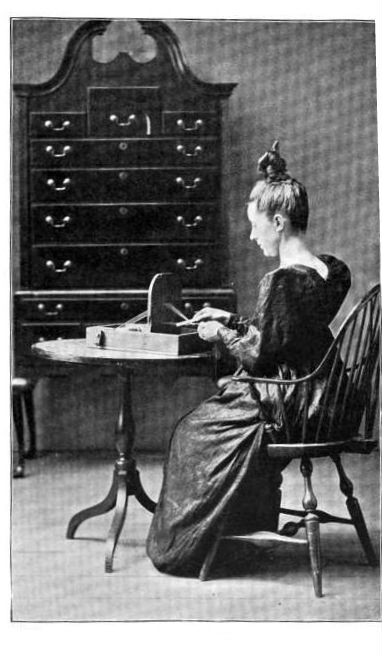

Photographs from Home Life in Colonial Days (1898)

"Americans cleave to the things of this world as if assured that they will never die, and yet are in such a rush to snatch any that come within their reach, as if expecting to stop living before they have relished them. They clutch everything but hold nothing fast, and so lose grip as they hurry after some new delight." --Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America (1835)

I will soon pick up stakes for a new home some 2,000 miles away. In preparing for what will be my third cross-country move in eight years, I've spent the last few weeks sifting through my effects, playing "eeny meeny miny moe" with everything from rhetoric guides to Römertopfs. The losers I haul off to Goodwill, the place where in many cases I found them. It's a lot of work, this constant getting and giving away. I find myself dreaming of nonattachment, of living like a Zen monk, with nothing to my name but a bowl and a grass mat.

Or perhaps nothing but an iron pot and a bedroll -- which, as I've reminded myself more than once these past few days as I box up or throw out my stuff, represented all the effects owned by most early Americans. In the 17th century, no more than half of Chesapeake families could claim household belongings worth more than £60. Only a small fraction of them owned chairs or benches, furnishings we take for granted today. Beds also were uncommon luxuries. Most families slept together on a single bedroll, or "shake-down," that could be rolled up and stowed away during the day. Effects usually considered essential to domestic cheer -- paintings, trinkets -- were conspicuously absent. If the man of the house happened to excel in carpentry or some other craft, his family might enjoy furnishings more lavish. But for the most part the colonial home held only the necessities.

"Searchers after horror haunt strange, far places. For them are the catacombs of Ptolemais, and the carven mausolea of the nightmare countries.... But the true epicure in the terrible, to whom a new thrill of unutterable ghastliness is the chief end and justification of existence, esteems most of all the ancient, lonely farmhouses of backwoods New England; for there the dark elements of strength, solitude, grotesqueness, and ignorance combine to form the perfection of the hideous." --H.P. Lovecraft, "The Picture in the House" (1920)

Necessity influenced the degree of austerity evident in a household. "They had no friends to welcome them," wrote William Bradford of his fellow Plymouth settlers, nor did they have "any houses or much less towns to repair to." Escaping the wet and cold of their adopted land thus became the first order of business. In the Chesapeake region homes were little more than "ramshackle hovels," as historian Edmund Morgan characterized them. Everyone, he observed, "lived in ... rotting wooden affairs that lay about the landscape like so many landlocked ships." As flammable as they were rotten, those that storms spared fire destroyed. Even when they withstood such threats, they offered little protection against the chill winds blowing off the Atlantic. "We had a fire," said an overnight visitor to a clapboard house in New Jersey in 1679, but the house was "so wretchedly constructed that if you are not so close to the fire as almost to burn yourself, you cannot keep warm, for the wind blows through everywhere." Yet such drafty, insubstantial dwellings were to be preferred to the caves and "English wigwams" inhabited by less fortunate colonists.

Not surprisingly, colonial mealtime often proved a subdued event. No dining tables heaped with tasty treats greeted the weary settler after a day's work. People gobbled without ceremony stew of boiled vegetable pulp or whatever else happened to be simmering over the hearth. They ate sitting on the ground or gathered uncomfortably around a long board set on trestles. One Massachusetts man living in 1650 relates how he "took up [his] dinner and laid it on a little table made on the cradle head." Sometimes diners made due with a motley assortment of stools, benches and chests. The food itself they scooped from a common bowl with their bare hands.

"Is it progress if a cannibal uses a knife and fork?"--Stanislaw Lee

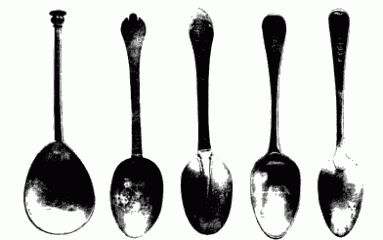

More affluent types might pass a single spoon among them, or they might share the household's sole knife. Indeed, individual place settings were unheard-of extravagances in the days before the Revolution.

Domestic life continued this way for some time. Annapolis, Maryland physician Alexander Hamilton (no relation to the man whose face graces the 5-dollar bill) related how, in 1744, he came across a family who dined on a "homey dish of fish without any kind of sauce," using "neither knife, fork, spoon, plate, or napkin." Their fingers their sole utensils, the family tucked into the meal, "cramming down skins, scales, and all." Another physician, writing of his early 19th-century childhood, recalled visiting a neighbor, one "Old Billy," who, with his sons, would "frequently breakfast in common on mush and milk out of a huge buckeye bowl, each one dipping in a spoon." And the sight of "a prettily dressed, nice-looking young woman ladling rice pudding into her mouth with the point of a great knife" left an indelible impression on Englishwoman Emily Farrar during her 1837 visit to the United States.

Domestic life continued this way for some time. Annapolis, Maryland physician Alexander Hamilton (no relation to the man whose face graces the 5-dollar bill) related how, in 1744, he came across a family who dined on a "homey dish of fish without any kind of sauce," using "neither knife, fork, spoon, plate, or napkin." Their fingers their sole utensils, the family tucked into the meal, "cramming down skins, scales, and all." Another physician, writing of his early 19th-century childhood, recalled visiting a neighbor, one "Old Billy," who, with his sons, would "frequently breakfast in common on mush and milk out of a huge buckeye bowl, each one dipping in a spoon." And the sight of "a prettily dressed, nice-looking young woman ladling rice pudding into her mouth with the point of a great knife" left an indelible impression on Englishwoman Emily Farrar during her 1837 visit to the United States.

"Rather go to bed without dinner than to rise in debt." --Benjamin Franklin

Strangely, these uncouth ways occasioned nostalgia. "I looked upon this as a picture of that primitive simplicity practiced by our forefathers long before the mechanic arts had supplyed [sic] them with instruments for the luxury and elegance of life" Dr. Hamilton wrote of the fish-eating family. Nineteenth-century Delaware homemaker Ann Ridgely worried that in becoming more sophisticated in their manners her children might lose "the sweet, innocent, engaging simplicity and industry of the peasant, despising extravagance, affectation, and frippery of all kinds." The hardship of the frontier bred virtues that with easier circumstances many feared would vanish.

Street, tavern and theater fights, labor strikes, and family murders all increased in the United States after 1790.

This yen for sweet, innocent, engaging simplicity likely owed to the rapid economic expansion that occurred between 1790 and 1830. Coaxed or cast from the farms that had sustained them for decades, people headed for the Atlantic seaboard's burgeoning cities in search of a living. There they found wage labor and all its attendant insecurities. Between people who only few decades before had considered each other equals there began to grow a divide

"The cursed foul contagion of French principles has infected us," lamented Secretary of the Navy George Cabot in 1798. "They are more to be dreaded ... than a thousand yellow fevers."

. During Dr. Hamilton's time, this divide was small (though in cities could already be found landless, underemployed drifters). By the time Ann Ridgely was fretting over the moral development of her children, the divide yawned wider. As society began to stratify, folks began to drink. Americans' affinity for hard liquor many historians date to this period. By 1825 some 3.7 gallons per capita were drained from tumbler and tun, thanks in large part to the demoralizing vagaries of a market economy. Pre-Revolutionary Americans may have had to scoop their mush from a common bowl, but at least they could take comfort in the fact that their neighbors did the same.

Recipe for Corn Stew from the Colonial Receipt Book (1907): "Take pieces of cold chicken, put the bones in the bottom of the kettle, cover with cold water and bring to the boiling point. Simmer gently for an hour and strain. Add to this stock the bits of chicken, two peeled tomatoes cut into squares, one green pepper chopped fine and the corn taken from one dozen cobs. Simmer gently ten minutes then add a tablespoonful of butter, moisten a tablespoonful of cornstarch in a little cold water, stir into the stew, add a teaspoonful of salt, half a teaspoonful of pepper and serve."

I've been reflecting on early American life as I box up the rest of my belongings and wait for the arrival of the 6' x 7' x 8' cube into which I will pile them. I'm down to a duffle bag full of clothes and a copy of Dmitry Merezhkovsky's

The Romance of Leonardo da Vinci, two of the few things I'll bring with me on my journey. With so little to my name (for the time being, at least), I feel the allure of that primitive simplicity enjoyed by the colonists. It's a most bearable lightness of being, one that reminds me just how much I belong to my belongings. And though I won't resort anytime soon to spearing breakfast with a knife or scooping mush from a wooden bowl, I have come to understand that the same forces that ping-pong me from coast to coast are also those that compel me to junk up my life.

Domestic life continued this way for some time. Annapolis, Maryland physician Alexander Hamilton (no relation to the man whose face graces the 5-dollar bill) related how, in 1744, he came across a family who dined on a "homey dish of fish without any kind of sauce," using "neither knife, fork, spoon, plate, or napkin." Their fingers their sole utensils, the family tucked into the meal, "cramming down skins, scales, and all." Another physician, writing of his early 19th-century childhood, recalled visiting a neighbor, one "Old Billy," who, with his sons, would "frequently breakfast in common on mush and milk out of a huge buckeye bowl, each one dipping in a spoon." And the sight of "a prettily dressed, nice-looking young woman ladling rice pudding into her mouth with the point of a great knife" left an indelible impression on Englishwoman Emily Farrar during her 1837 visit to the United States.

Domestic life continued this way for some time. Annapolis, Maryland physician Alexander Hamilton (no relation to the man whose face graces the 5-dollar bill) related how, in 1744, he came across a family who dined on a "homey dish of fish without any kind of sauce," using "neither knife, fork, spoon, plate, or napkin." Their fingers their sole utensils, the family tucked into the meal, "cramming down skins, scales, and all." Another physician, writing of his early 19th-century childhood, recalled visiting a neighbor, one "Old Billy," who, with his sons, would "frequently breakfast in common on mush and milk out of a huge buckeye bowl, each one dipping in a spoon." And the sight of "a prettily dressed, nice-looking young woman ladling rice pudding into her mouth with the point of a great knife" left an indelible impression on Englishwoman Emily Farrar during her 1837 visit to the United States.