In these dark and brooding times it is Kafkaesque tragicomedy that strikes the right note of collective mirth. The Iranian government recently staged an anniversary celebration of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini's momentous return from exile in France. The cardboard reenactment of his arrival has been the subject of effusive internet mockery since photos from the state-affiliated Mehr News Agency (taken by photographer Ruhollah Yazdani) proved it was not, alas, an insurgent Photoshop hack operation but an official ceremony.

On February 1, 1979 Khomeini, who would become the steward of the revolution, descended the stairs of a chartered Air France Boeing 747 as three million Iranians turned out on the streets of Tehran to salute him.

Now, 33 years after those prophetic moments, the richly deserved ridicule that Cardboard Khomeini has received is an indicator of the profound upheavals, divisions, and contradictions that have characterized modern Iranian history.

Once you regain yourself after laughing at the photos of the 2012 ceremony there's something deeply serious and ironic to consider: as a consequence of the revolution Khomeini himself would turn into a figure of majesty, even divinity. He who denounced immodestly dressed women as 'coquettes' (the Shah referred to them as 'dolls') has been dwarfed into a string puppet. There's a measure of pathos that elaborate stately images strike. These make a sad pauper out of the regime.

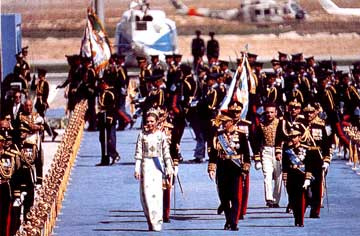

Every time a historical event of seismic importance is glorified in Iran, it fails spectacularly. The Shah's infamous Perspolis moment, when the royal family's extraordinarily lavish, multi-million dollar ceremony marking 2,500 years of the Persian Empire outraged Iranians and turned them irrevocably against the monarchy.

The Shah's idolatrous visions were shattered by one of the most important revolutions of the twentieth century. The current show of idolatry is merely shattered by laughter, and the distant banging of US-Israel war drums (or unmanned drones, unprecedented sanctions, and scientist assassinations, as the case may be).

I find myself more interested in what is really real in these photos than what constitutes simulacra of the real. The Cardboard, escorted by guards solemnly holding each two-dimensional side of him, descends the official Islamic Republic of Iran airplane. The bristly green garlands of the plane, the sharp red edges of the staircase, and the curvacious aviator hats of the officers are all three-dimensional surfaces that put the spotlight even more harshly on the cardboard's flatness. That flatness adds to the image's hilarity, with a tinge of pity for the performed gullibility of those displaying it: don't they see how idiotic this looks.

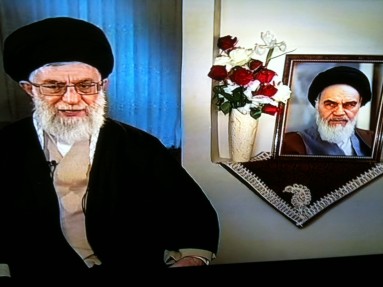

Rows of officers extend roses—real roses—a recurring decorative image whenever Khomeini or a revolutionary martyr is shown. (Here is a photo I took off the television on the advent of the 2011 Iranian new year, as Khamenei morosely announced the Year of Economic Jihad with Khomeini's simulacra, and a vase of roses, by his side.)

Cardboard Khomeini is descended to the tune of a musical procession of trumpets. (Khomeini did after all eventually legalize music).

The officers salute the cutout. A lone guard looks back at the camera. Yo, is this for real real?

The most remarkable photo is a peculiar sort of simulacrum, one that would have fogged up Walter Benjamin's glasses: it is a cutout of Khomeini and his escorts, frozen in time, descending the staircase.

Things only get more delicate from there. The New York Times' Lede blog writes: 'Shortly after the airport arrival, another cardboard cutout made an appearance in southern Tehran at Refah School, which served as Ayatollah Khomeini’s base of operations. There, it was joined by officials, including the education minister, who sat in a large circle with the silent version of the revered leader and awkwardly drank tea.'

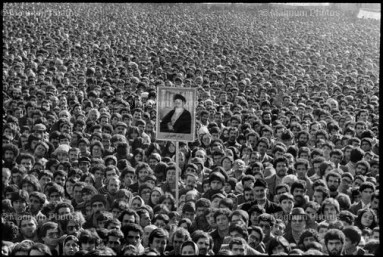

Jasmin Ramsey notes how the king-wears-no-clothes absurdity of the cardboard printout stands in contrast to the photographs of Khomeini's picture being held up by thousands of adoring crowds at Tehran University in 1979. The contrast between that photo and the empty space of the tarmac in the 2012 images is stunning.

True to form there is already a Cardboard Khomeini meme, culturally referenced in detail. The most meta shot is Khomeini gazing at Charles Foster Kane, who points to his own publicity photo.

Cardboard Khomeini holds a personal, if inopportune, significance in the form of a childhood memory. My uncle belonged to one of Khomeini's banned political parties. A few years into the revolution he was prohibited from ever entering the country again. Yet he wanted to marry a woman from Iran, and because the wedding demanded the presence of extended families, it was decided the event would be officiated without him. To those involved, an absentee ceremony seemed as natural a cause (under the strained circumstances) as any.