By Erica Eisen

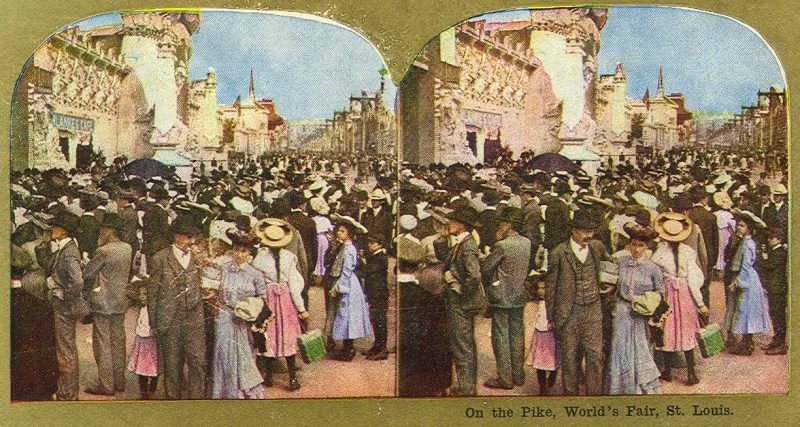

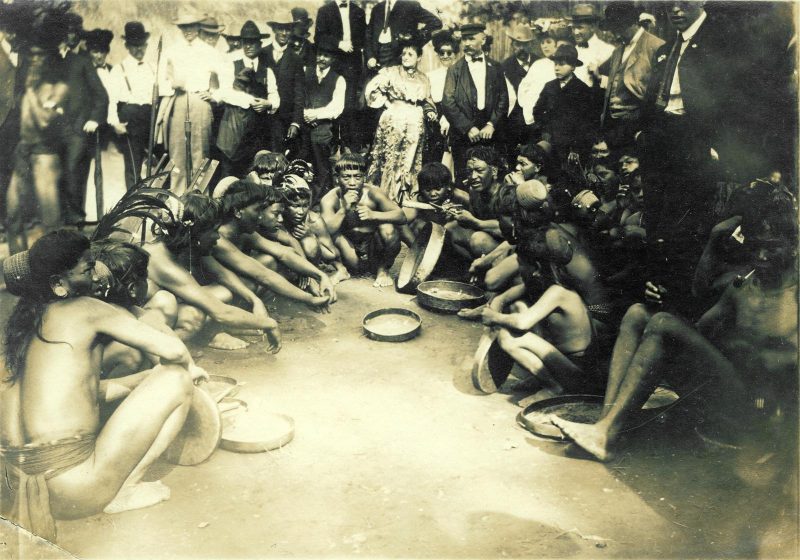

If visitors to the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair grew bored of strolling along spectacular purpose-built waterways or lolling through the grand pavilions of arts and industry, their wandering search for diversion might have taken them to the Philippine Reservation. Stretching across 47 acres, the reservation held over 1,000 native Filipinos who had been brought to the United States expressly for the shock and delight of white fairgoers: in one prominent spectacle, Igorot tribespeople were required to slaughter and eat a dog each morning as visitors looked on.

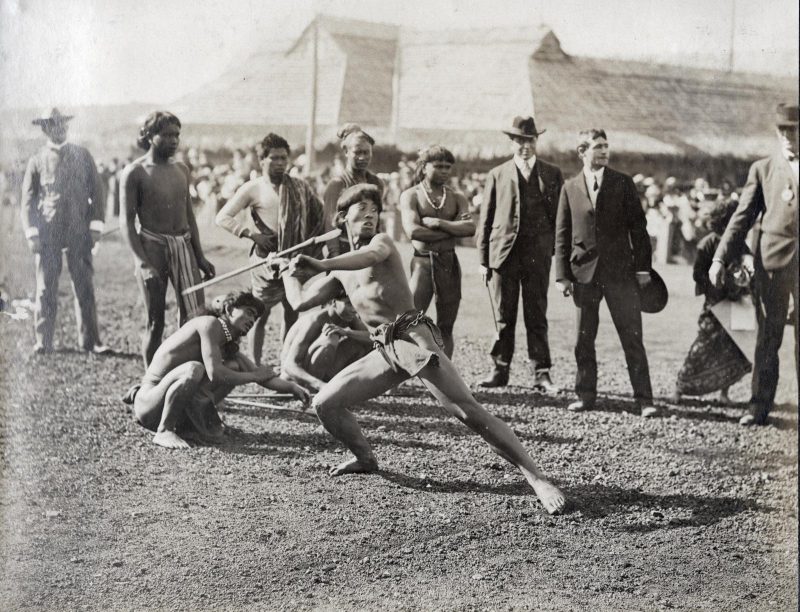

The Philippine Reservation was but one of a panoply of “living exhibitions” available at the exposition’s human zoo, in which indigenous people from around the globe –– as well as their food, dress, architecture, games, and religious rites –– were converted into fairground attractions. Exhibition organizers hoped to demonstrate to the world that ethnic groups could be definitively ranked according to biological and cultural markers of civilization –– and that in this ranking, the United States came out on top. To accomplish this goal, they turned to a perhaps unusual tool: sports. Products and proponents of the masculine-coded, hyper-militaristic ideology of American imperialism, the Fair organizers believed that athletic competitions among the inhabitants of the “living exhibitions” could serve as a useful microcosm for testing the martial worth of a nation at the level of the individual (male) citizen. These competitions would also be a method for determining which peoples lacked the strength and virility to govern themselves.

Though likely consumed as a thrilling spectacle by the majority of its almost 20 million attendees, the 1904 World’s Fair was viewed as something far more than mere diversion by the countries who took part. In the pavilions and grand exhibition salons, among the camel riders and the cotton candy-sellers and the fairgoers impatiently queueing for the ferris wheel while whistling “Meet Me in St. Louis,” nation jostled against nation to project political might and impress its own narrative of superiority upon the passing crowds. The Louisiana Purchase International Exposition, the official title of the St. Louis World’s Fair, was designed to fete the namesake territorial expansion and laud the United States’ growth into a military and technological powerhouse in the intervening years. The show’s spirit of empire reflected a century of American westward expansion at the expense of enslaved peoples, Native Americans, and the environment. Cannons bristled at visitors to the US War Department exhibition; organizers brought in classic items and replicas of Americana like Abraham Lincoln’s log cabin and Theodore Roosevelt’s hunting lodge. The human zoo –– which featured not only Filipinos (the US had recently acquired the Philippines as a colony) but also Native Americans, Congolese, Ainu, Patagonians, and other indigenous peoples –– was of a piece with the Fair’s broader goal of demonstrating Western cultural superiority and touting conquest.

The clearest expression of the Fair organizers’ desire to order and to rank the peoples of the world came with an event known as Anthropology Days, which pitted indigenous people from the human zoo against each other in a series of athletic competitions that served as a covert means of gathering anthropometric data to support white supremacist theories. These events were of a piece with the period’s broader currents of scientific racism, whose proponents sought to identify a biological basis for race and racial supremacism. Scientists gauged cranial capacity to argue for racial differences in intelligence, and they measured noses, foreheads, and arms in an attempt to cast African people as a less-evolved “missing link.” In athletic competitions, metrics like speed and strength could be employed to argue the same case.

The anthropological displays at the fair were under the custodianship of William John McGee, who had been recruited because he was at the head of the Bureau of American Ethnology, a division of the Smithsonian Institute devoted to researching and recording Native American cultural practices. After McGee was selected to head the Anthropology Department of the St. Louis World’s Fair, he declared that the aim of his work would be to “present human progress from the dark prime to the highest enlightenment, from savagery to civic organization, from egoism to altruism.” To illustrate his idea of the teleological progress of civilizational development –– one in which the West was understood to be at the pinnacle of achievement –– McGee oversaw (as had other World’s Fair organizers before him) the creation of “living exhibitions.” Meanwhile, the plan went, McGee and other anthropologists would be able to harvest data from their captive subjects in support of their theories on the racial order. But McGee’s experiments quickly ran into a roadblock: consent. Many of the zoo’s occupants refused to be photographed or measured, presenting a major obstacle for his data collection.

A new avenue for study seemed to present itself when McGee was approached by James E. Sullivan about the possibility of a collaborative effort. As well as being head of the fair’s Department of Physical Culture, Sullivan had a leading role in the creation of the 1904 Olympics, which were taking place in St. Louis, and was himself a former athlete. Sullivan was also a committed white supremacist who believed that the genetic superiority of northern Europeans was manifested in their peerless athletic prowess, an idea he shared with the many eugenicists and racial scientists of his day. Yet he had lately heard “disturbing” accounts of remarkable physical feats performed by peoples from around the world. Sullivan had therefore been extremely interested to hear of McGee’s plan to bring together indigenous peoples from across the globe. McGee’s human zoo, he proposed, presented the perfect opportunity to collect athletic data (without the knowledge or consent of the subjects) that would confirm both men’s beliefs about the order of the races –– might the two work together? McGee, whose original attempts at collecting anthropometric data had become virtually unworkable, agreed.

The events that comprised what the organizers dubbed the “Special Olympics” took place in mid-August. Although McGee and Sullivan conceived of their data collection as scientific and objective, circumstances reveal the uniquely imperialist and American (or Western) assumptions about testing and proving physical prowess. The hastily thrown-together program left the participants (all of whom were men) with no time for the kind of rigorous physical training undertaken by the white athletes competing in the “real” Olympics, nor did the indigenous athletes receive a properly translated explanation of the rules. What’s more, the events were undermined by the American organizers’ assumptions that their understanding of athletics was universal rather than culturally constructed. The starting shot and the tape at the finish line, which the footrace organizers failed to adequately explain to the athletes, left a number of runners perplexed. Indeed, many participants simply did not subscribe to a Western understanding of racing in the first place, preferring to wait patiently for friends rather than charging ahead without regard for others. The cultural arrogance of the events’ organizers was the nail in the coffin of their already specious idea that the Special Olympics might yield data points permitting a statistically valid interracial comparison.

Although the poorly organized competitions were plainly a shambles, McGee and Sullivan did not hesitate to use the individual performances showcased therein as the basis for broad conclusions about entire ethnic groups. McGee concluded that the Special Olympics “established in quantitative measure the inferiority of primitive peoples…in that coordination of mind and body which seems to mark the outcome of human development and measure the attainment of human excellence.” Sullivan’s own report frequently elided details that showed Native athletes in a positive light, such as the fact that they universally bested the white American pole-climbing record by at least 10 seconds. They failed to consider the role that lack of practice, adequate rule explanations, or emotional investment in the outcome might have played in indigenous athletes’ performances. As such, McGee and Sullivan’s unwillingness or inability to see the deeply flawed nature of their own research exemplifies how imperialist jingoism and notions of martial masculinity were embedded in supposedly objective scientific endeavors of the period.

The dazzling pavilions of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition were not built to last: constructed of a hemp-plaster mixture known as staff, the vast majority (many already showing wear and tear) were pulled down after the fair had run its course. But the ideologies in which the proceedings were rooted seem far hardier. A recent article for The New York Times reports that Nobel Prize-winning biologist James Watson has doubled down on previous baseless claims that there is a genetic basis for different IQs between races. Watson, whose work has supplied fodder for white nationalists looking to bolster their claims with supposedly scientific evidence, is hardly alone in his beliefs. Though St. Louis’s global Potemkin village is gone, the work of dismantling the intellectual foundations the fair left behind persists.

Further Reading

Susan Brownell, The 1904 Anthropology Days and Olympic Games: Sport, Race, and American Imperialism (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008)

Nancy J. Parezo and Don D. Fowler, Anthropology Goes to the Fair: The 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007)

James W. Vanstone, “The Ainu Group at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, 1904,” Arctic Anthropology 30, no. 2 (1993): 77-91, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40316339.

Lady Science is an independent magazine that focuses on the history of women and gender in science, technology, and medicine and provides an accessible and inclusive platform for writing about women on the web. For more articles, information on pitching, and to subscribe to our newsletter, visit ladyscience.com.