The Betty Crocker company’s book, Starting Out: How to Get the Most Out of Your Home, Furnishings, Food, Money (1975) begins, as so many books of this sort do, by inviting young couples reading it to daydream about their first home. Will they nab hip urban digs complete with picture windows and ficus-ready terrace? Perhaps there awaits a handsome townhouse with private patio for outdoor entertaining. If they heed Aunt Betty’s advice, which covers everything from “taking care of your refrigerator” to the “vital do’s and don’ts of credit,” these young lovebirds will no doubt put themselves in a position to make their dreams a reality.

I picked up a copy of Starting Out at a poky little thrift store eking out its catchpenny existence in some postindustrial armpit I found myself in one weekend. I enjoy such books and have collected whole piles of them, as well as home economics textbooks and other catechisms of the post-Rooseveltian middle class.

It’s not just the American middle class that interests me, however. My collection spans cultures. Time Life’s The Cooking of Scandinavia (1968) occupies a privileged place on my bookshelf. The cover features a large glass jar of marinated herring and red onions flanked by a hunk of Nøkkelost (cheese flecked with caraway seeds) and a tumbler of aquavit. The contents offer useful, interesting information. You read about how Finns occasionally suffer from “salt hunger,” how Swedes adore certain cuts of meat, and how Norwegians favor mashed rutabagas over potatoes.

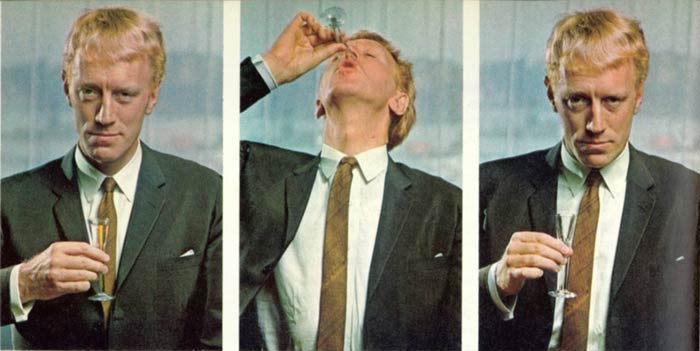

Like Starting Out, The Cooking of Scandinavia paints a seductive picture of postwar domestic comfort of the sort that peace and social democracy made possible. Actor Max von Sydow appears in a photo-triptych, modeling “How to Skoal with Style.” In the first panel, he meets the reader’s gaze. Glass in hand, he wears a slight smile. The second panel shows him imbibing, the caption below it reading, “Tipping his glass backward, von Sydow drains the chilled aquavit in one deceptively cool gulp.” In the third he again meets the reader’s gaze. He wears a different smile, and his glass, now empty, he holds aloft. Across the page from von Sydow a photograph features two shirtless, Swedish picnickers also enjoying aquavit. In the background, a blue sailboat bobs in a bay.

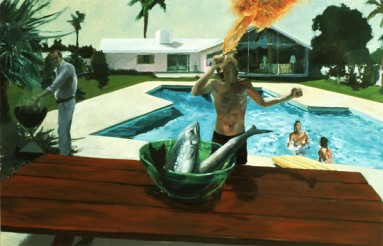

A few pages past von Sydow’s toast there appears a section entitled “A Sauna Before Supper,” which depicts a gathering hosted by Aarne Ervi, one of Finland’s “brilliant young architects.” “Naturally,” we read in the accompanying text, “the eating ritual is best when practiced in beautiful surroundings—such as a handsome modern home.” In one picture, Ervi and some complexly-coiffed guests swim in a rectangular pool. In another, they tear into plump, pink pork-and-mutton sausages roasted over an open fire in Ervi’s dressing room. An evening scene shows the same individuals waving glasses of vodka and laughing. The evening sun, half hidden behind a grove of tall pines, shines through a window that takes up the entire wall, illuminating a table laden with boiled carrots, poached salmon, white potato pudding, and “sauna-cured leg of lamb.”

When I began collecting Cold War–era cookbooks, how-to guides and life manuals thirteen years ago, the economy was bustling, nourished by the manna of dotcom stock jobbing profits. Today, however, these books sitting around my apartment seem documents from a vanished world—Work and Leisure in Ultima Thule, perhaps, or Homemaking in Atlantis—one which was pried away by force of massive low-interest leverage, or was patiently ladled out of the ship of state during various bailouts. They seem a collective memento of prosperity and equality that is not likely to return in my lifetime.

I’m reminded of a scene in George Orwell’s 1984. Winston Smith comes across a paperweight in a downmarket curio shop. The narrator, focalizing through Smith’s consciousness, describes the bauble as “a heavy lump of glass, curved on one side, flat on the other, making almost a hemisphere.... At the heart of it, magnified by the curved surface, there was a strange, pink, convoluted object that recalled a rose or a sea anemone.” It’s an object strange to Smith, a relic from a time when individuals invested in such trifles to make their homes cozier and more pleasant. You imagine along with Smith the paperweight holding down a stack of letters on an écritoire in a Victorian-era brownstone. Smith reflects that what “appealed to him about it was not so much its beauty as the air it seemed to possess of belonging to an age quite different from the present one.”

Perhaps that’s why I haunt thrift shops, which luckily seem to proliferate these days. Unlike Winston Smith, however, who admits people his age cannot remember a time before the revolution—which, ironically enough, flushed out the capitalists who were “the lords of the earth”—I can recall when middle-class life seemed a reasonable prospect for me and my cohort, and I often find myself elbow to elbow with members of older generations who are capable of intoning the epos of bourgeois dominion.

That dominion at an end, a newly revised Starting Out is in order. But what would such a thing look like? Under my editorship it would be present- rather than future-oriented, and it would exult an ethic of making do: “Need hors d’oeuvres that pass for fancy tonight? Stir a tablespoon of cod liver oil into a jar of capers and you have something approaching caviar.” Or: “Cheap wine tastes much like Opus One when poured over a bay leaf.” Entire chapters would be devoted to advice on living, if not stylishly, then passably while servicing debt: “Balloon payments on student loans are but a cabbage away.” It would be a handbook for the subprime peon. A guidebook for the existentially mortgaged. A primer for the precariat.

A Starting Out for the precariat wouldn’t hold out the promise of social and economic mobility, of rewards reaped for effort expended. In his uplifting 1897 book Suicide, sociologist Emile Durkheim discusses what happens when an individual comes to confront the futility of his efforts. “All man’s pleasure in acting, moving and exerting himself,” he writes, “implies the sense that his efforts are not in vain and that by walking he has advanced.” But what if the individual doesn’t advance? These moments of perceived injustice, which naturally increase during periods of economic upheaval, he soon finds intolerable. Unable to adjust to society’s new conditions, he commits a sort of inverted auto-da-fé that Durkheim calls “anomic suicide.” “At every moment of history,” he continues, “there is a dim perception, in the moral consciousness of societies, of the respective value of different social services, the relative reward due to each, and the consequent degree of comfort appropriate on the average to workers in each occupation.” When that perception is troubled, when society perceives that certain individuals receive too much while others receive too little, despair increases; and this despair corrodes society, crippling, if not destroying, lives.

Yet to capitulate to the situation outlined by Durkheim would be to confirm Ozzy Osbourne’s thesis that suicide is the only way out, and I prefer not to glean life lessons from a washed up hair-metaller. Instead I take my cues from Jean-Paul Sartre. “Well, well ... let’s get on with it,” Garcin in No Exit demands of his cellmates, who have grown hysterical. As long as we have free access to information, as long as we retain enough control over our everyday lives to create meaning, as long as we continue to enjoy freedom enough to agitate for justice and fairness, we can indeed get on with it. We might not make a heaven of hell, but we can at least make it into an inviting Finnish sauna.