Illustrations from Irma Blanchard Matthews's Under a Circus Tent (1907)

An earlier version of this post appears at the original Austerity Kitchen

Of those who could claim to have rested their head on a lion's lower jaw Isaac van Amburgh was the first. An intrepid animal trainer, he accomplished feats of derring-do that went unmatched in his time. He and his pride of tamed felines became something of an international sensation, commanding the attention of no less estimable a personage than Queen Victoria, who commissioned a portrait of him, so deeply had his talents impressed her

Someone deemed "lion-sick" suffers illness brought on by love.

. Others among the great and good stood equally astounded. The Duke of Wellington once reportedly asked Van Amburgh, "Were you ever afraid?," to which the celebrated lion tamer responded, "The first time I am afraid, your grace, or that I fancy my pupils are no longer afraid of me, I shall retire from the wild beast line."

Whether real or feigned, the fearlessness displayed by Van Amburgh remained a crucial element of his success. Doubters suspected, however, that more than courage lay behind the animal tamer's art. Some suspected that Van Amburgh kept his cats in line by means of a crowbar, though in truth he employed a method similar to that described by Thomas Frost in his 1875 book, Circus Life and Circus Celebrities. Frost reveals that a wise lion tamer procures his "beasts as young as he can" and wins their trust by feeding them with his own hands, first from the outside of their den, and then at closer quarters, all the while taking care to face them. This keeps in check a "dormant devil" residing in their breasts

Ellen Bright, the famous nineteenth-century lion tamer who exhibited her talents at Wombwell's menagerie, met her end at the age of seventeen, when a tiger mauled her

. Once he wins from them a measure of trust, the tamer essays a caress, stroking the cat "down the back, gradually working up to the head, which he begins to scratch." The lion responds as all cats do by rubbing his head against the tamer's hand. At this point, the tamer introduces a board and teaches the feline to jump over it.

I ran away from home with the circus, / Having fallen in love with Mademoiselle Estralada, / The lion tamer. / One time, having starved the lions / For more than a day, / I entered the cage and began to beat Brutus / And Leo and Gypsy. / Whereupon Brutus sprang upon me, / And killed me. / On entering these regions / I met a shadow who cursed me, / And said it served me right.... / It was Robespierre! -- Edgar Lee Masters, "Sam Hookey" (1916)

Only once the tamer has won this trust can he attempt the showstopping feat of placing his head between the animal's teeth. Gentle lashes on the back with "a small tickling whip" condition the lion to receive his mouthful. The tamer then "press[es] him down with one hand," and with the other raises the lion's head. Taking hold of its nostril with the right hand and the under lip with the left, he parts the creature's jaws and places his head between. The perils attending his vulnerable position do not end with a possible bite; he must also ensure that the lion does not claw his face. How such an expert lion tamer as Van Amburgh achieves stardom becomes plainly evident in this breathtaking routine.

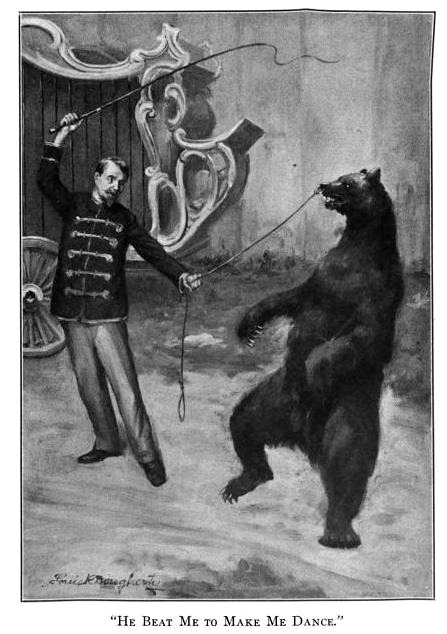

"Bruin! Bruin! / Thou art but a clumsey biped! ... And the mob / With noisy merriment mock his heavy pace, / And laugh to see him led by the nose! ... themselves / Led by the nose, embruted, and in the eye / Of Reason from their Nature's purposes / A miserably perverted." -- Robert Southey, "The Dancing Bear" (1799)

The marquee attractions of Victorian circuses, the big cats commanded the lion's share of top-quality food. The menu du jour of Alexander Fairgrieve's famous traveling menagerie offers some sense of the pecking order among the animals. Elephants had to content themselves with "hay, cabbages, bread and boiled rice, sweetened with sugar" while the felines feasted on "shins, hearts, and heads of bullocks." So much meat did the lions and tigers of the great circuses consume, in fact, that their fellow carnivores the bears had to await the onset of "very cold weather" before they could enjoy similar provisions. Until such time, they subsisted on bread, sopped biscuits and boiled rice. A hard life indeed the dancing bear lived, and his humiliations garnered little reward.