(A guest post from Jungli Pudina, which will be posted in three parts: today, Wednesday, and Friday.)

Some time ago, I got involved in a court case in which three children of a Pakistani-American Muslim couple - Jalal and Husna Ahmed - were taken away by the Child Protective Services in California, and kept in foster homes for 6 months. According to the attorney of the mother, this was the most expensive “parental neglect” case that she had seen in 20 years of family law practice.

I became involved two weeks before the trial was to begin. Jalal Ahmed had contacted the Council of American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) for help, a female worker at CAIR - Amira - had spoken to the lawyers to understand the needs of the case, and then sent an email on the CAIR listserv. An acquaintance forwarded this email to me, highlighting the phrase that is highlighted. I was outraged, and utterly confused. Three kids taken away because the youngest one got himself into an accident? Criminal charges on the mother? Threat of deportation?

Subject: South Asian Muslim family in need of assistance

Dear friends: Assalaam alaikum. I’m writing because a distraught father who is a new immigrant from rural Pakistan contacted CAIR asking for help. The family moved here from Rawalpindi and they have three children, two little girls, ages 6 and 4 and a little boy age 2.

The mother was boiling water on the stove and she left the kids while she went to the bathroom. The little boy managed to climb up on the stove and burned his hand because he stuck it into the pot of water. The mother treated his burn with honey and salt, but did not take the child to the hospital. She cannot speak any English and she is afraid to be out with the children in their area because she doesn’t feel safe. The next day, the father took the child to the hospital but because the couple could not adequately express themselves, the doctors found discrepancies in their story of what happened to the boy. When the doctors coupled this with the fact that they did not take the boy in for so long, they began to suspect abuse and called CPS. CPS removed the children from the home and they began looking over the couple very carefully. I spoke to the father’s lawyer and she believes the couple is innocent and that the children were wrongfully removed. The lawyer told me that certain actions are being interpreted as unfit parenting when it seems like there may just be cultural explanations for why the parents did not, for instance, bring the boy to the doctor immediately. The mother is facing criminal child neglect charges and the father may also be charged. The mother may also face deportation. At present, the lawyer is looking for a few resources which I am hoping you may be able to help with:

a) The mother will be required to take parenting classes, but she cannot read and write and can’t understand English. The lawyer believes that if we could find a community volunteer to help the mother learn her materials for this class, this may satisfy the court’s requirement and facilitate getting the children home to their parents. We would need a woman fluent in Urdu/Punjabi who could volunteer some of her time to help a family in need.

b) The lawyer is also interested in finding an expert witness to testify about cultural and family practices in rural Pakistan, perhaps a sociologist, anthropologist or even a community leader familiar with the culture there, in order to try and help the court understand what the parents believe about child-rearing and counteract the effects of stereotypes.

c) Also, the father has been asking everyone and anyone in the community for help who might be able to help him. The lawyer really believes it is a wise idea for him to stay quiet and has counseled him not to talk, but he is desperate to get his kids back. The lawyer thought it might be a good idea to have an Urdu/Punjabi speaking attorney who could facilitate client communication and possibly get through to the father that he needs to stay quiet.

Any help or direction you might provide would be greatly appreciated. You are also welcome to contact me with any questions at the office. Jazakum Allahu Khairan.

I replied to the email, and a couple of days later, met with the attorneys.

Megan: “And I’m the father’s attorney.”

Pudina: “Hmm…why are there two attorneys for the parents?”

Megan: “The kids have a separate attorney too. This is the way these cases happen. The mother, Husna, has criminal charges on her. The court might decide that Husna is innocent, in which case all three children will be returned to the parents. The course might decide Husna is guilty, in which case only Jalal will get custody. The court might decide that both parents are unfit, in which case the kids will permanently be in foster care. The kids have already been without their parents for 5 months.”

Pudina: “So where is the abuse?”

Megan: “The doctors suspected that the mother had intentionally harmed the child, because the parents didn’t immediately take Chotu to the hospital. The language barrier must also have created confusion. And so they called CPS, who took all three children away. The charge is for failure to treat injury, as an average American family would. We think it would be very helpful if you testify as an expert witness on family life in rural Pakistan, and how it’s common to treat children at home, instead of taking them to hospitals which might be far, expensive, or unsafe.”

Pudina: “I’ll do all I can to help the case. And you are right, it’s common to treat burns at home in rural Pakistan. But this is really not about rural Pakistan. I grew up in urban Pakistan where we could afford good hospital care. I remember how my brother got burnt at a very young age - badly burnt - and my mother treated him at home.”

Lily: “Yes that’s what Husna and Jalal say. Growing up in a big extended family in their village, they saw many burns, and all were treated at home. So they can’t understand what’s the big deal.”

Pudina: “Exactly. But actually, this is not even about Pakistan. I was speaking to a white, American colleague of mine about this case. He has a special child, who has serious emergency situations every week but they don’t take him to the hospital. They think it’s healthier to manage the child at home. Within four blocks of this cafe, you will find twenty different families with twenty different approaches.”

Lily: “Jalal and Husna are very worried about their kids. The kids have been moved around in four foster homes, and the current foster parents are not caring at all. The family is not Muslim, and the kids have contracted lice and pinworms. They have had to eat non-Halal meat which is upsetting for the parents. The foster home also has a dog who licks the children, and that too is very upsetting for the parents. Why is that, by the way?”

Pudina: “Keeping dogs at home is considered ritually unclean by many Muslims, including my own parents. People may have animals at home, particularly those that give nourishment - chickens, goats, cows. But dogs, for many, are not ok.”

Megan: “You know Husna was even jailed for three days.”

Pudina: “WHAAT? Thats just inSANE.” I try to control my anger. Breathe.

Megan: “Criminal charges were filed against her on the pressure of the social worker working on the case, who was convinced that Husna had intentionally burnt her child. The social worker kept calling the District Attorney and Police, insisting that they press charges.”

Pudina: “Does the social worker have kids of her own?”

Megan: “I don’t think so. She has a Masters in Social Work.”

Pudina: “What does Husna wear?”

Lily: “She wears Pakistani clothes (shalwar kameez). She covers her head, too.”

Pudina: “Do you think that there is some sort of racism happening here?”

Megan: “The social worker is definitely hostile to the family. I think she fears them.”

My fingers reach for my head, eyelids press, with sadness, seething.

* * *

I think later about the images of Muslims and Pakistanis that dominate the media in the US. Taliban. Al-Qaeda. Madrassas breeding terrorists. Muslim men oppressing Muslim women. Nuclear weapons. Total de-humanization, to cover up the total devastation that has been raged by American imperialism in the region since the Cold War.

When I tell people in random street encounters that I am from Pakistan, sometimes I actually see their inner selves step back, and a subtle glimpse of fear emerge on their faces. This, when I am an English-speaking woman without a headscarf, often in sleeveless clothes - and that’s how I am in the US as well as in Pakistan. Perhaps it is that I don’t match their media-created monolith of the Muslim/Pakistani woman, or that they are just trying to battle the images of terror that might leap to their minds. “Really?”, some say, because they don’t know what else to say. “Wow”, others say. To some, just being from Pakistan is an accomplishment. Just to avoid the looks and queries, or because I am in a rush, I have sometimes said India. Not untrue either, my parents came from there and I am not willing to allow nationalism - very new in our world’s history - to make me disown my Desi-Indian-South Asian heritage. For India, I might hear: “That’s wonnnderful. I love ____” where the dash might stand for yoga, sagh paneer, or other such things. It’s cute. People immediately try to connect. For Pakistan, they are not sure. There is awkwardness, a hint of fear, and sometimes a desire to immediately disconnect.

Yes, of course, this is not always the case. But it is often the case, especially given the fear-mongering discourse on Pakistan in the US. There are seasonal Muslim threats - Somalia in the Summer, Yemen in Fall, Sudan in Winter, Iran in Spring. Pakistan is Perennial.

What must the social worker think of Husna, a Pakistani Muslim woman in shalwar kameez who covers her head? Egyptian-American scholar Sahar F. Aziz argues that because of ignorance and vicious media-generated misinformation, a Muslim American woman donning a headscarf - of any form - is often automatically perceived to be an unassimilable foreigner, a subjugated victim, and the terrorist other. Co-workers can thus tell a headscarf-wearing woman that her scarf is a “disgrace” and a “symbol of 9/11 to customers.” Men might harass headscarf-wearing women, saying that they spent time in Iraq and “my friends were killed by you” - oh the levels of violence and tragedy in that. Cases of hate crimes on Muslim women have also escalated over the last three years. Women have been punched, kicked around, and have had their headscarves ripped off. In one case, a Muslim woman’s 4-year old son was also attacked, leading him to bleed.

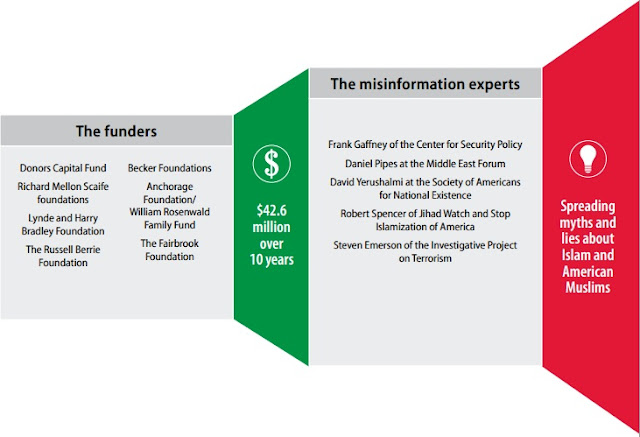

This blood is the direct result of the ways in which the right-wing establishment here has poisoned the blood of Americans, with vitriolic anti-Muslim rhetoric at home and violent military campaigns abroad. In a meticulously researched report, “Fear Inc: The Roots of the Islamophobia Network in America”, the Center for American Progress details how more than $40 million was spent over the last 10 years to create a fear of Islam and Muslims in America, by a “small, tightly networked group of misinformation experts directing an effort that reaches millions of Americans through effective advocates, media partners, and grassroots organizing.”

It is not surprising then, that a 2010 poll by the Washington Post/ABC News showed that 49% of Americans have an unfavorable view of Islam, up from 39% in 2002. That’s half of all Americans, and we are two years beyond the poll. It’s not a coincidence. It’s not “understandable” after 9/11. It’s organized. It’s a consequence. As the report goes on to argue, the current campaign against Muslims echoes previous witch hunts in American history, against other racial, ethnic, and religious groups such as Japanese Americans.

* * *

Pudina: “This is legalized, racialized abduction. Just like Muslim men might get manipulated and entrapped by the FBI and thrown into prisons, or be renditioned, tortured, and kept without rights in Guantanamo Bay, Muslim children are now being abducted and thrown into foster homes.”

The attorneys are slightly taken aback. But they seem to see the point.

Megan: “The social worker also asked really silly questions to Jalal. For example he was asked: In Pakistan, did you eat? Jalal replied: No I didn’t, tell her she’s talking to my ghost right now.”

Pudina: “So what do we do?”

Megan: “Well, we need you to testify about parenting, family life and health practices in Pakistan. But it would also be useful if you can help us discover some information we need for the case, and generally serve as a communication channel with the parents.”

Pudina: “Ok, sure.”

Lily: “For example, you know Husna keeps bringing up Allah. You ask her anything and she invokes Allah. This is not going to help her in court.”

She must be saying Inshallah - God willing - at the end of her sentences, I thought. Like so many Muslims culturally do, just regularly, and randomly. I’ll see you next week, Inshallah. I’m graduating this semester, Inshallah. Its modern equivalent would be “hopefully.” Indeed, as my spiricher (spirit-friend and teacher) Roshni Rustomji shared with me, the Spanish word Ojala comes fromInshallah. The rate of Inshallahs in a conversation exponentially increases in a situation of crisis. My kids will be back soon, Inshallah, I imagined Husna as saying to herself, comforting herself.

But she could also just be saying Ya Allah, or Oh God. My dear Greek friend, Maria, was once telling me about the Urdu words she had picked up from me. Yaar - friend, mate, and a filler term that can be inserted just about anywhere in any conversation. Bus - enough, done, stop.Haan/Accha - ok, good, right, really. Chalo - walk, move on, let’s go. Such ordinary words that may be said in many ways, their meanings changeable depending on the tone and context, words that I don’t know how to do without. While I felt sheepish about my tendency of using Urdu terms with people who clearly do not speak the language, I was also pleased that she had picked them up so well.

Maria: “You also say a lot of religious things.”

Pudina: “Haan? What are you talking about?”

Maria: “You say Ya Allah, Hai Allah, Mashallah.”

Pudina: “Ohooo most of the times it’s like saying ‘Oh God!’ or ‘For Heaven’s sake!’ It’s cultural.”

Maria: “Ohhh I get it. But it sounds so religious!”

Yes, I think now, because “God” is in English, the Market-proclaimed, Empire-stamped standard. That’s why it sounds normal. “Khuda” and “Allah” is the normal God of Muslim cultures, but it appears religious in the Western context. After all, in these times, the Western world only understands Muslims in terms of Islam as religion - not culture, not politics, not music, not poetry - just Islam. And that too, a particular kind of religion - one that obsesses over the veil, and the madrassah. In the post 9-11 context, invocations of Allah sound not only religious, but also deviant, even scary. I have been told that I need to speak softly when I once instinctively said Uff Allah - Oh God - on a flight. This, when one is not even saying anything religious. My sister the other day was reciting a beautiful prayerto my niece, which had Allah in it. My brother-in-law said: “Oh no, we have to be careful before saying that to her.” “What?!”, I said. “Why??”. “Bhai we live in Alabama, not California. I don’t want her to go to school saying Allah this and Allah that.”

Yes, we must eternally censor ourselves. Out of fear. And to fit in. Uff Allah!

Lily: “I told Husna that invoking Allah won’t help her, she must help herself. You need to explain that to her.”

Pudina: “Ok I will explain that to her. Saying Allah this and Allah that can indeed be problematic in court.”

Megan: “When Husna is being questioned by authorities, she also keeps saying ‘yes’ when she is not understanding much. She is just eager to please, to say yes to everything so that she can get her kids back. But she must not say ‘yes’ to anything she doesn’t understand. Plus she keeps moving back and forth with her body, I don’t know why. That is unsettling. You need to tell her to avoid doing that.”

Pudina: “Yes, I’ll tell her to avoid doing that.”

Lily: “It would be very useful if someone from the community could visit Husna and help her with operating on her own, and learning English. Husna must take parenting classes in which she learns American concepts of discipline, like time-outs. We have to show that they are assimilating well into American culture.”

I saw the point. I also saw it’s full circle. From Anthropology and Schooling’s imperial origins to the Human Terrain System to forced assimilation under conditions of legalized, racialized abduction.

Pudina: “Sure.”

Megan: “See also if you can find out: was Husna overwhelmed with the children? Was she keeping them cooped up inside? That’s one of the charges against her, and as the father’s lawyer, I need to know about that.”

Pudina: “Do you have kids?”

Megan: “Yes, two”.

Lily: “Yes, three.”

Pudina: “Were you not overwhelmed when they were young? Are you still not overwhelmed?”

They pondered, and understood, simultaneously.

Pudina: “I don’t have kids, but I have eight nieces and nephews from my siblings. I was with my sister for post-care after her delivery. It was all about changing diapers, washing the bottles, feeding, burping, putting to sleep, soothing. I also visited my brother after his twins were born. That was just incredible. I didn’t know night from day, didn’t step outside for days, and didn’t have the energy or care to notice the outside world either. This, when I am not even the mother. This, when I can drive and afford to go out.”

They nodded, with a knowing smile. “Oh yes, we remember that.”

Did Husna keep her kids“cooped up”? I thought later that Husna has three young children and faces all the overwhelming challenges that every mother faces. Plus, she doesn’t have a car. Her husband drives a taxi and comes home late at night. What is she supposed to do? It’s not just about being a mother, it’s about class too, you know.

Megan: “Speaking of motherhood, Husna keeps mentioning her mother all the time. She literally calls her mother every day.”

Lily: “Ya why does she call her mother every day?”

The look and tone of how-strange-is-that.

I sighed. It hit me, the irony and the tragedy of their genuine confusion, and of this situation. Husna’s motherhood is being judged, violated, and criminalized in a context where calling one’s mother every day is considered decidedly odd. Ya Khuda.

It must seem to them that I would share this context, since I looked and spoke more like them. English-savvy, Western-clothed. My relationship with my mother has seen its ups and downs, for sure. We have had strong disagreements, and there have been times when we have not been the most pleasant to each other. As relationships are, this might continue for as long as we live. But we talk regularly. And if we don’t, something feels amiss in the universe. I have Pakistani friends who do not call their mothers regularly for whatever reason, but they would never find daily communication with one’s mother odd - and certainly not in a time of crisis. Why else was the phone invented?

Pudina: “I speak to my mother every day, or every couple of days. This does not include our emails and Skype video chats. If either of us is going through a stressful situation, we might even speak twice a day. Who else does one call in a crisis?”

Lily: “Well…the therapist.”

For Husna, Allah is the therapist, her Mother is her therapist. She probably also has Sisters and Aunts who are her Therapists. It’s about cultural difference, but again, it’s about class too you know.

I began to think more about motherhood in Pakistan, since I had to testify about it in court. Ma kay paaon kay neechay jannat hoti hai - Beneath a Mother’s feet lies Paradise - one of the first sayings I learnt, attributed to Prophet Muhammad. You learn it at home, in the community, on TV, in school, in religious school, it may even be graffiti on the walls, a poster on a tree. Beneath a Mother’s feet lies Paradise.

I thought about motherhood more universally.

“It is my belief that a mother’s love is the foundation of every love that follows; it is the primary love relationship - the first that humans experience, and as such, a profound influence on all subsequent and secondary relationships in life. It is a relationship that surpasses all reason.” The beloved Mumia Abu-Jamal says it all. Mumia ji, you are truly the creator of Beauty. I love Gandhi and Nelson Mandela too, and believe that we can learn from everywhere, but why escape to India and Africa to find causes, to find inspiration? They’re always around us, wherever we are, and it’s pertinent to engage with them at home because that means confronting our own oppressions. It’s been thirty years and Mumia is still incarcerated. Right here by the US State. And Baba Jan has been imprisoned for ten months now. Right here by the Pakistani State. Both victimized because they stand for Truth, Freedom, and Justice. And Husna? She is victimized simply because she is a Muslim mother.

I also began to think more about family life in Pakistan, since that was to be the central part of my testimony. The family, in Pakistan, is more than just the nuclear household because extended relationships and kinship ties are deeply valued, and provide the primary community in which children are raised and socialized. They say that a language reflects the lifeworlds of its speakers, their frames of meaning, thought, and value. Tellingly, then, relatives are not mere “Uncles” or “Aunts”, or called solely by name. Familial relationships in Pakistan/India have distinct identifiers that must have developed over centuries. Here's a sampling:

Bhai/Bhaiya - Brother

Bhabhi - Brother’s wife

Behan/Apa/Aapi/Baaji - Sister

Behnoi/Jeeja - Sister’s husband

Khala/Maasi - Mother’s sister

Khalu - Mother’s sister’s husband

Mama/Mamu - Mother’s brother

Mami/Mumani - Mother’s brother’s wife

Fui/Phuppi: Father’s sister

Fua/Phuppa: Father’s sister’s husband

Wada Bapa/Taya: Father’s elder brother

Wadi Ma/Tai: Father’s elder brother’s wife

Chacha: Father’s younger brother

Chachi: Father’s younger brother’s wife

Dewar: Husband’s younger brother

Dewrani: Husband’s younger brother’s wife

Jaith: Husband’s older brother

Jethani: Husband’s older brother’s wife

Saala: Wife’s brother

Saali: Wife’s sister

Bhaanja: Sister’s son

Bhaanji: Sister’s daughter

Bhateeja: Brother’s son

Bhateeji: Brother’s daughter

To many of these relationship-titles, one might add jaan at the end. Jaan - that immensely beautiful term meaning Life, Spirit, Soul, Love. Bhai jaan would then mean - Brother of my Soul, my Lovely brother, Brother-Life. That’s how cherished these relationships are supposed to be. That’s how cherished Love itself is. Witness the many ways for referring to a beloved soul: yaar, jaan, jaaneman, jigar, dost, rafeeq, habeeb, sanam, sajan, dildar, piya, mehboob, saaqi, saiyaan, mitwa. At least fifteen words, just in the Gujrati-Urdu-Hindi tongue that I am familiar with. Including dialects, there are more than 60 languages in Pakistan, and more than 400 in India. Imagine, the richness of relationships. Imagine, the possibilities of life. Another World is not just Possible, there are at least 460 Worlds Existing in the part of the earth that gave me birth. In this warm and welcoming part of Earth, beyond family and loved ones, even strangers are highly esteemed. In southern Pakistan, I heard that strangers are to be respected as guests because Khuda (the Divine) might sendFarishtay (Angels) in the form of strangers. In northern Pakistan, I heard that the Divine himself comes in the form of strangers.

Lily: “Husna is so sweet Pudina…at the end of every phone call, she says ‘Thank you Mam, I love you.’”

(Part two and three will be posted Wednesday and Friday)