Dressing meat and stuffing sausage meant being a cut above the rest

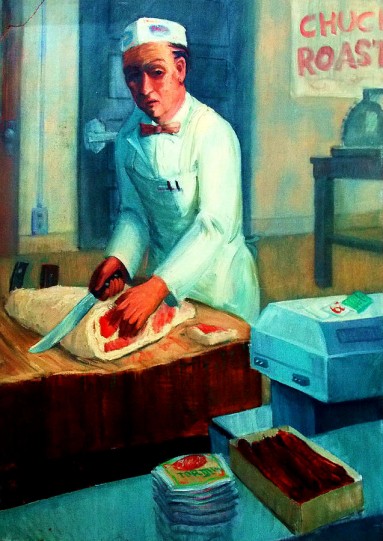

Boris Grigoriev, German Butcher (1917)

"It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest." --Adam Smith

A schoolmaster's kindness spared Henry Mayhew from a night spent under the stars. The 19th-century British journalist had been traveling through Germany in search of "principal Lutheran localities," as he put it, and found himself in the Thuringian town of Möhra, ancestral home of that confession's founder. Road-weary and famished, Mayhew arrived at the town's lone inn only to learn that traveling bookbinders and visiting land surveyors had claimed all beds. His search for lodgings led him to the schoolmaster, who might have a room to let.

As it happened, the schoolmaster did have a room. The accommodations proved less than ideal. Where Mayhew should have found a washstand stood a piano; where he should have found a wardrobe, another piano. Determined to keep a stiff upper lip, he reasoned, "A wise man can live anywhere."

Marc Chagall, Butcher (1910)

"When the girl came into the kitchen in the morning at the busiest moment of the day's work, they grasped hands over the dishes of sausage-meat. Sometimes she helped him, holding the skins with her plump fingers while he filled them with meat and fat. Sometimes, too, with the tips of their tongues they just tasted the raw sausage-meat, to see it it was properly seasoned." --Émile Zola, The Belly of Paris (1873)

Whether a wise man can eat anywhere was another question. Having made himself at home, Mayhew approached the schoolmaster's wife to learn what was to be served for dinner. He was told: "Here gives liver-sausage, and red-sausage, and Savoyard-sausage, and hard sausage --." This recitation Mayhew interrupted by stating he would like ham. Sadly, there gave no ham. Nor did there give chicken, the village's last capon eaten by the surveyors. As with the chicken so it was with eggs, vanished down those same gullets. To an exasperated Mayhew's query, "Well, then, what can you let us have?," came the reply: "Here gives liver-sausage, and red-sausage, and Savoyard-sausage, and hard sausage...."

And so sausage was Mayhew given, along with sauerkraut and pickled plums. Though he "couldn't have been less partial to sausage-meat," he admitted, "the infinite variety of sausages made and consumed in the land" commanded his admiration.

Abraham van Strij, Butcher in His Shop (1810)

"Farther down were extraordinary opportunities to buy Leberwurst, Blutwurst, Jagdwurst, Brühwürtchen, and a host of other appetizing garbage." --Harry Franck, Vagabonding Through Changing Germany (1920)

There was much to admire: sausage egg-shaped and sausage round-barreled, sausage blond and sausage gray, sausage flecked white with fat and sausage blue-black with blood. "Indeed with the sausage alone," one Englishman noted, "Germany might form a rampart round the world." These defenses might consist of the ample Cervelat of Braunschweig, the diminutive Lübecker Saucisschen, the velvety Strassburger Truffelwurst, the coarse-grained Frankfurter Bratwurst, or any number of other plump links. Sausage in its local distinctiveness betokened something of the patchwork quality of the region itself, with its many states, palatinates, cities and towns.

"'My daughter married to a sausage-maker!' said Regina in a bewildered tone. ¶ 'There's nothing in that,' Alfred Whittaker rejoined; 'there's nothing in that, my dear girl, provided he makes his sausages good and wholesome and enough of 'em. But I was afraid it would be a bit of a blow to you.' ¶ 'My daughter -- my daughter married to a sausage-maker!' Regina repeated." --From John Strange Winter's The Little Vanities of Mrs. Whittaker (1904)

Constant among such variety was the butcher, his Metzgerei, or butcher shop, the laboratory in which he performed his prodigies of pork. A magic hand at meat-dressing generally, he was revered and often asked to preside over riotous celebrations. Once or twice a year he and others of his trade paraded behind a flower-bedecked bullock, waving knives and cleavers, dancing and jumping. To these capers townsfolk assigned great importance: the higher the butchers' leaps, the higher that year's grain.

Annibale Carracci, The Butcher's Shop (1583-1585)

The 7th-century Cypriot Bishop Leontios of Neapolis relates that St. Simeon, the patron saint of holy fools, wore a string of sausages around his neck like a wreath.

Of uncommonly great importance were Nuremberg's butchers. Thanks to a privilege granted them by Holy Roman Emperor Charles IV for their loyalty and protection during a revolt of the city's artisans, they presided over the Shrovetide festival. Very much a feast of fools, it inspired its lords to attempt great feats. One such feat, attempted in 1658, came in the form of a 300 foot long, 700 pound black sausage. Beribboned and hoisted aloft on poles, this monstrous tube of meat served as the standard for its makers' guild. This standard was struck later that evening and eaten at a public banquet. To the delight of stomachs throughout Nuremburg, each year saw the city's butchers vying to top the previous year's effort.

"In the evening we go down and eat liverwurst and bread, a most toothsome combination. The company was hilarious; I feared some one would fall into the open tubs of minced meat. Some liverwurst put out on boards to cool fell prey to a dog, who sneaked up and, seizing a link, fled in the darkness. Some one said impatiently, 'Herr Gott! Noch ein mahl?'" --Alexander Gunn, The Hermitage–Zoar Note-book and Journal (1902)

The life of a butcher wasn't all fun and games. Among other privileges accruing to a him were license to carry a sword and authority to set meat prices. His trade often summoning him to the countryside, he offered to carry written correspondence for a fee. He and his fellows thus became Germany's first mail carriers. This service they rendered became known as "butcher post" (Metzgerpost).

Fernand Leger, The Butcher Shop (1921)

In Falk Harnack's 1951 film The Axe of Wandsbeck Hamburg butcher Albert Teetjen must decide if he will serve as executioner to four communists.

Responsible townsmen to the letter, butchers appeared to do no wrong. In their uprightness they garnered the esteem even of great artists. A butcher surprising Joseph Haydn at home one day with a request for a minuet for his daughter's wedding had his wish granted. The Austrian composer told him to come back the next day to claim his piece.

"There is a story of a wealthy Berlin butcher whose son had been promoted in the army by Moltke, and who, to show his gratitude, advised the field-marshal never to eat sausage." --Henry J. Finck, "Multiplying the Pleasures of the Table" (1912)

The butcher did so. Moments after handing the him the score and bidding him farewell, Haydn heard faint music outside. He went to his balcony and saw the butcher accompanied by a wandering orchestra and a large ox. The animal wore gilt horns and bright colors. "Sir, you have done me a very great favour," said the song's claimant, "and I thought a butcher could not better express his thanks for so beautiful a composition as your minuet, than by presenting you with the finest ox in his possession." Whether Haydn made sausage of the butcher's gift has gone unrecorded, but the gift did make history. So touched was the composer by the gesture that he called his composition "The Minuet of the Ox," the title by which it is known today.

Bill Joseph Markowski, The Butcher (date unknown)

Recipe for "Cervelatwurst" from Ludwig Flentje's Haus-Rezepte (1872): Six pieces lean pork and one fatty chopped into fine pieces. For every 12 pounds of meat add 12 "loths" (16 and 2/3 grams) salt, 4 loths coarsely ground pepper, 1/2 loth saltpeter and 1/2 cup rum, red wine or water. Fill sausage casings with the stuffing, and hang the sausages two to three weeks in a dark, airy smokehouse, and then store them later in a dry, airy place.

Titles and privileges enjoyed for centuries came under assault in the mid-19th century, when industry and government conspired to push venerable butchers from their pedestal. The Schlachtzwang law of 1868, which permitted municipalities to build public slaughterhouses, opened the meat trade to official scrutiny. Any meddling butchers thwarted by keeping their sausage recipes secret and moving their abbatoirs beyond city limits. Their resistance they managed to sustain for decades. As late as 1920 American butchers remarked that their German brethren "are mostly butchers of the old school, proud of their 'independence' and disinclined to deal with any large corporations." This resistance proved futile. In Germany as in the United States, man surrendered to machine, and large corporations uprooted small proprietors. As the 20th century wore on the butcher who slaughtered his own meat and made his own sausage became a rare sight. Yet he better than anyone likely understood that such was the way of all flesh.