These fixtures of American towns dominated local markets but were later liquidated by corporate competitors

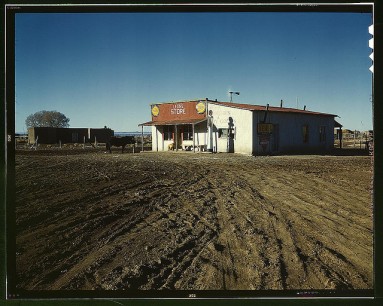

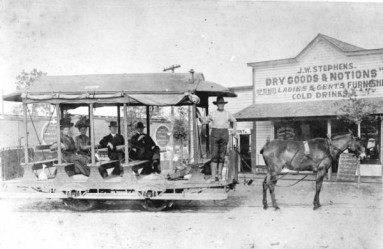

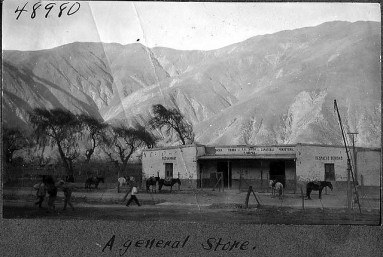

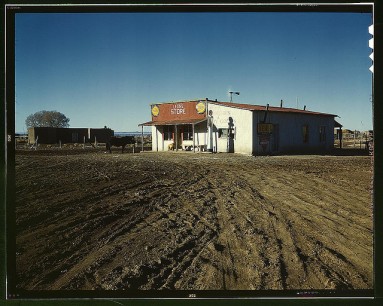

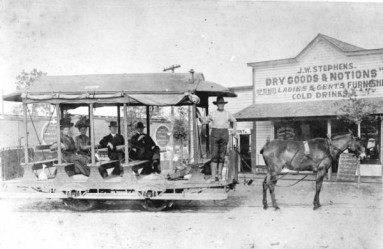

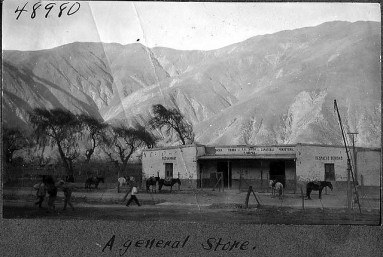

Various photographs of country stores, 1890-1940

"We're rapidly approaching a world comprised entirely of jail and shopping." --Douglas Coupland

I’ve been shopping at a certain store known more for busting unions and bloating welfare rolls than for peddling quality goods. It's pretty much the only mercantile action in my small Rust Belt town. The mom-n'-pop shop hale enough to have withstood the Walmart

Wehrmacht is rare in even the biggest burgs. Where I live they're like snow leopards or skunk apes: rumored to exist but seldom seen. So with a heavy heart I step into the fluorescent glare to sift piles of shoddy junk to find whatever it was I thought I needed that day. I guess you could say I've been big-boxed in.

"One evening Sam, now grown to man's stature and full of the awardness and self-consciousness of his new growth, was sitting on a cracker barrel at the back of Wildman's grocery. It was a summer evening and a breeze blew through the open doors swaying the hanging oil lamps that burned and sputtered overhead. As usual he was listening in silence to the talk that went on among the men." --Sherwood Anderson, Windy McPherson's Son (1916)

Knowing what commerce in a small town used to be like makes my inevitable shopping forays even more disheartening. In days past local general stores fulfilled the function since usurped by strip malls and superstores. Lively places, they sold just about everything: edibles from English walnuts to Florida oranges, household items, farm equipment, clothes, seeds, and so on. Long counters crowded with such goods ran along either side of the interior, with rounded glass showcases set atop them every few feet. Drawers, bins, and shelves spanned the length of the side walls. In them hid linens, spices, soap, hardware, tools, and cutlery. There was more besides. Huge wheels of cheese sat under screen cages. Barreled cukes gently bobbed in brine. Buggy whips dangled from the ceiling, as did corn poppers, lanterns, pails, and kitchen tools. On wooden pegs hung lamp chimneys, horse collars, and bouquets of dried apples. In the store's rear huddled rakes, hayforks, adzes, scythes, and other heavy hardware.

"How dear to my heart! To remember the barrel! / Alluring the lazy to sit there at ease! / My soul is inspired to a crackery carol / That flows with the breath of the odorous cheese. / I want to go back to the sleepy old village, / To tread once again the dim pathways of yore, / The grocer's dried beef case and cheese box to pillage / And lounge on the barrel that stood in the store." --Anonymous, "The Old Cracker Barrel" (1906)

This eclectic array of merchandise not only gave general stores a signature appeal. It gave them a signature smell, as well. Social historian Gerald Carson writes that "diarists and old timers agree that it was a well-dug-in odor, with lots of authority, a blend made up of the store's inventory, the customers and the cat." Adding to the aroma were "ripe cheese and sauerkraut, sweet pickles, the smell of bright paint on new toys, kerosene, lard and molasses, old onions and potatoes, poultry feed, gun oil, rubber boots, calico, dried fish, coffee, and 'kept' eggs." (By "'kept' eggs" Carson means "eggs that should have been shipped off to the city some time ago but weren't.")

"The superior man understands what is right; the inferior man understands what will sell." --Confucius

General stores were often as much a feast for the mind as for the senses. Many boasted book departments, and quite large ones at that. Indeed, they were the Amazon of their day. It was reported that one especially ambitious storekeeper bankrupted one of the best-known booksellers. This event riled bibliophiles. Though many agreed with the general storekeeper, who, as one journal put it, "answers that in these days of universal education the public knows what it wants," customers found themselves torn between its interests and its sentiments. "In spite of the fact that the general store sells books for a third less than the bookseller did," the same journal goes on to note, "the reading public, will ... deplore the disappearance of the bookseller who knew and loved his wares."

"For the merchant, even honesty is a financial speculation." --Charles Baudelaire

Deplored the bookseller’s disappearance may have been, but the general store was universally celebrated. Whole families came to gawk at goods. Mothers inspected the latest fabrics or patented foods newly arrived from New York or Boston. Fathers gossiped, munched crackers, and warmed their toes by the pot-bellied stove. Children ogled peanut roasters, barrels of brined Chesapeake oysters shipped fresh from Baltimore, and the many candies on display. Because customers came knowing what they wanted, shopkeepers felt little need to tout their wares. They were free, then, to attend to keeping a tidy establishment, which they at any rate preferred to hawking. "Advertising don't take the place of dustin'," one successful merchant proclaimed.

Still, some of their brethren disagreed, believing that a little bit of swag goes a long way. In summer, one especially enterprising proprietor would give out small fans bearing his store's name and address. Yet truth in advertising proved as dicey a proposition then as it ever has. "Fresh," as it applied to pork sausages, may have meant scraped of mold and burnished with butter. At one Prospect, New York store rumor had it that two grades of molasses issued from a single barrel. Another store's miraculous barrel managed to house three grades of port wine ranging in price from 25 cents to a dollar a pint. Storeowners could only plead necessity as a defense. "We must live and thrive, you see," said one merchant of his unscrupulous ways.

"From the standpoint of figures the country storekeeper is an important man. Out of all the retail business in the United States nearly one establishment in every four is classed as a 'general store,' doing its trade with farmers or people in small towns. There are fully two hundred and forty thousand of these general stores among the million-odd establishments of all kinds that perform the retail distributing in city and country." --From "The Country Store and Its Trade: A Growing Field for Aggressive Merchants" (1911)

General-store proprietors were more often than not honorable men of diverse talents to boot. Besides peddling every good under the sun, they served as town clerks, custodians of the land records, and justices of the peace. Many could doctor a horse, offer legal advice, and draw up a sound contract. They even dispatched mail as postmasters general, fourth class. More than mere merchants, general store proprietors were pillars of the community, and it was to their store that people came to keep abreast of town events. Matrons tacked to store bulletin boards notices of church socials. Farmers posted advertisements for produce auctions and turkey shoots. Around cracker barrels took place talk of crime, politics, or the weather. Over all this activity storekeepers presided, enthroned behind their roll-top desks.

"Corporation: An ingenious device for obtaining profit without individual responsibility." --Ambrose Bierce

Storekeepers had every incentive to see this activity continue. Like it or not, their fortunes were yoked to those of the community. Business ebbed and flowed with the seasons. To ease lean times they extended credit, often for six months or more, and trafficked in kind as well as coin, accepting eggs and milk as payment. Sometimes, however, it was the shelf stock itself, rather than any terms of its sale, that brought about their undoing. Demon alcohol especially could work great devilry on their books. "Oh, it is a horrible business," complained one shopkeeper about his bibulous neighbors. "When I set up my store at this corner, there were within a mile, a great number of able, thriving farmers; but now about half of them are ruined; and many of them were ruined at my store. And there is not a store in the country that sells ardent spirit, but what tends to produce similar results."

"Pure Sugar Stick Candy (The Old Time Kind)" from Rigby's Reliable Candy Teacher (1920): "25 pounds sugar, 2 teaspoonsful cream of tartar, 1 gallon water. Cook to 280 degrees, then pour two-thirds of the catch out on a greased slab, then cook the remaining batch to 330 degrees and pour it on the slab. But in the meantime, pull the first two-thirds batch on the hook, leaving all the air in possible. Flavor to suit. Now pull the small batch on the hook, and then in front of the table furnace form it as a wrapper around the large batch. If striping is desired, stripe the inside pulled batch. Be sure the ends of the wrapper meet smoothly and evenly to make an even seam. Pull the batch out in stick candy size and cut in lengths of four inches. In a few days the inside of the stick will grain and become creamy. The outside wrapper will also become this way. Keeping this kind of candy in air tight containers greatly helps it. The pure sugar stick is one of the oldest candies on the market, yet because of its merit, the sale is large."

As ardent as general store proprietors may have been in their vocation, the spirit of the times did not favor them. The 1870s saw the rise of department stores, which sold an exotic array of goods at prices that seldom fluctuated. These new juggernauts of the urban landscape drew customers from the provinces and dispatched mail-order catalogs to them. The effects of their reach were felt everywhere, reports of unfair freight charges, damage in transit, and shoddy merchandise notwithstanding. "Parcel post, rural free delivery and mail order houses are ruining business," lamented one country merchant. Storekeepers in the South, made desperate by the competition, spread rumors that Sears, Roebuck & Company founder Richard W. Sears was black. The retail giant answered this slur by printing Sears's photograph in its catalogs. Antagonism in the North, meanwhile, was tinged more by class than race, its central mythos that of virtuous small businessmen locked in struggle with immoral "Chicago millionaires."

The general store proprietor may have lost the struggle, but he has since come to claim a moral victory. Much like their predecessors the department stores, Target, Walmart, and the like sell everything under the sun at deep discounts. Their fortunes don’t follow those of any one town, and they seem to profit most when their customers (and employees) stay poor. After all, it's hard to market sane values in a world of crazy-low prices.