Tobacco and cotton may have enriched the American South, but pork and corn fed it

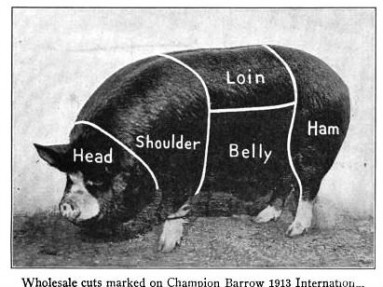

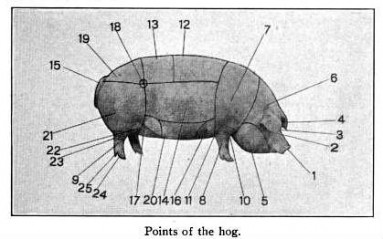

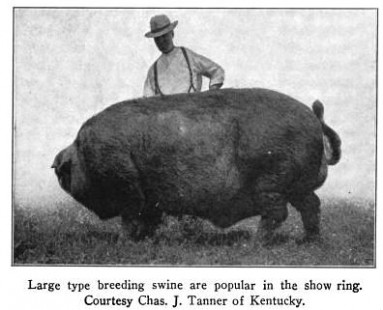

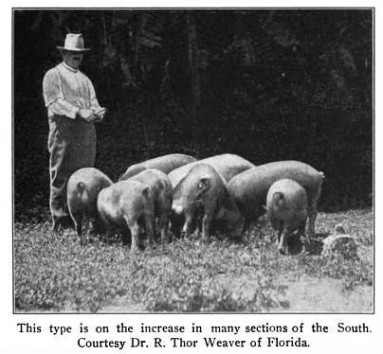

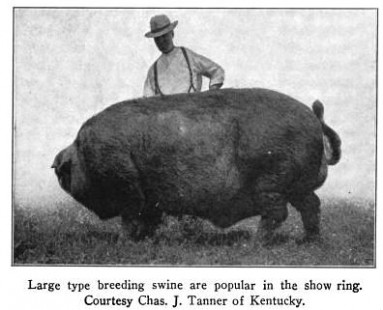

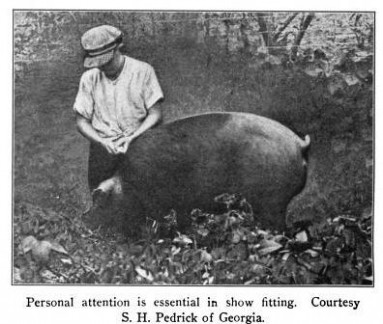

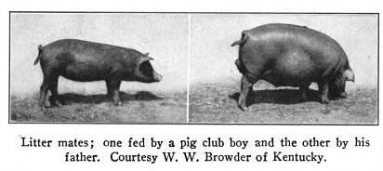

Illustrations from Southern Pork Production (1918)

Of the many miles Swedish merchant and man of letters Carl David Arfwedson traveled throughout the United States some of the toughest, as he would later note in an 1834 account of his wanderings, lay between Columbus, Georgia and Ft. Mitchell, Alabama. Rutted, rock-strewn, sometimes disappearing altogether in dark woods, the way at one point sent wayfarer, horse and carriage tumbling headlong into a river. The perils of rough passage were compounded by those of rough company. Cutthroats and bandits stalked the area, adversaries against whom Arfwedson’s guide, a seven-year-old boy, would likely not prove much use. Eventually there came into view a hut hidden among the trees, a discovery Arfwedson no doubt made with relief.

In that hut awaited hospitality almost as rough as the road itself. Its occupant, described by Arfwedson as a "real Amazon" of a woman, drank whiskey like water. Her guest she served a mound of pickled pig's feet

"CANNIBAL, n. A gastronome of the old school who preserves the simple tastes and adheres to the natural diet of the pre-pork period." --Ambrose Bierce, The Devil's Dictionary (1906)

, another mound of bacon slathered in molasses, and black bread soaked in whiskey. The first two dishes Arfwedson only picked at; the third he refused. The dinner, he later reported, was "the most singular of its kind I ever sat down to."

Said James Fenimore Cooper's frontierswoman: "Give me the children that's raised on good sound pork afore all the game in the country."

Though perhaps singular for someone likely reared on codfish and boiled potatoes, the meal served Arfwedson was not at all unusual. Early Southerners ate a rather limited and unvarying diet. At table the famished guest seldom found more than bacon, corn pone, and coffee sweetened with molasses. Pioneering sociologist Harriet Martineau complained that "little else than pork, under all manner of disguises" sustained her during her visit to the American South

For the most part, slaves observed the same diet as poor white farmers. Though many kept gardens, and thus supplemented their rations of pork and corn with a wide variety of vegetables, they had otherwise little opportunity to augment their diet.

. Another traveler griped that that he had "never fallen in with any cooking so villainous." A steady assault of "rusty salt pork, boiled or fried ... and musty corn meal dodgers" brought his stomach to surrender. Rarely did "a vegetable of any description" make it on his plate, and "no milk, butter, eggs, or the semblance of a condiment" did he once see. New Englander Emily Burke observed that "the people of the South would not think they could subsist without their [swine] flesh; bacon, instead of bread, seems to be THEIR staff of life." On this staff they leaned heavily. "You see bacon upon a Southern table three times a day either boiled or fried."

"They eat the Indian corn in a great variety of forms; sometimes it is broken to pieces when dry, boiled plain, and brought to table like rice; this dish is called hominy. The flour of it is made into at least a dozen different sorts of cakes; but in my opinion all bad." --Frances Trollope, Domestic Manners of the Americans (1832)

Southerners had reasons for preferring fare so unvarying. They thought pork the best meat for working people. It was tasty, simple to rear, and, unlike beef and mutton, easy to preserve in a hot, humid climate (an important quality in a time before such modern marvels as ice boxes). So central was preserved meat to the Southern diet that curing techniques became matters of pride.

"The United States of America might properly be called the great Hog-eating Confederacy, or the Republic of Porkdom," said Dr. John S. Wilson in 1860.

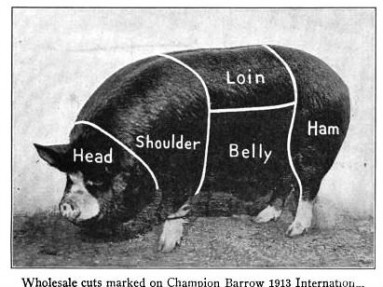

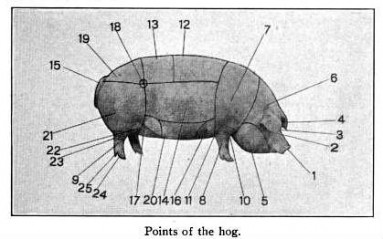

Each farmer had his own secret mix of preservatives and spices, usually some combination of pepper, alum, ash, charcoal, cornmeal, honey, sugar, molasses, saltpeter and mustard, which he slathered on shoulders and legs before salting and smoking them. What could not be salted or smoked was pickled. Snouts, feet and everything in between found its way into a brine. What could not be salted, smoked or pickled -- a pig’s backbone, ribs and offals, usually -- was cooked and eaten soon after butchering.

"Pig -- let me speak his praise -- is no less provocative of the appetite, than he is satisfactory to the criticalness of the censorious palate. The strong man may batten on him, and the weakling refuseth not his mild juices." --Charles Lamb, A Dissertation Upon Roast Pig (1822)

Pork's natural complement, corn in some form Southerners consumed throughout the year: roasted green in its shuck during summer; during autumn cut from its cob, ground into meal, mixed into batter and baked into griddle cakes and waffles. Sometimes they set batter in a warm place to culture into "sourings." Cornmeal batter admitted of seemingly endless variety. In its pure form, it consisted solely of meal, salt and water. Bakers of greater invention and means tossed in buttermilk, shortening, eggs or -- the most heavenly enhancement of all -- cracklings. So long as it contained corn, Southerners thought the resulting loaf or biscuit

What meal didn't end up in cornbread went to making whiskey.

better than any other, indeed preferring it, as English naturalist Philip Gosse noted on his visit to Alabama, "even ... to the finest wheaten bread."

"Heap high the farmer's wintry hoard / Heap high the golden corn! / No richer gift has autumn poured / From out her lavish horn!" --John Greenleaf Whittier, "Corn Song" (1915)

When vegetables appeared at table, they often did so as sweet potatoes and turnips. The first was easily grown and stored and wholesome. The second possessed all the virtues of the first, plus it yielded abundant edible greens and roots. Turnip greens (and often the roots as well) Southerners boiled with bacon, a preparation that left them with "pot liquor," a nutrient-rich broth, which they drank with gusto. In addition to farming potatoes and turnips, more ambitious families hunted and fished. Their diets they supplemented with wild turkey

"Today I saw a lot of wild turkeys," wrote David Harris in his farm journal for 1858, "and among the other was one find old goblar; I have marked him as mine."

, duck, venison, rabbit, squirrel and the much beloved catfish.

"The belief has been expressed that had not the Pilgrim Fathers discovered this golden grain in the first winter they landed on our shores, this 'land of the free and home of the brave,' would to-day be an 'unsolved problem.'" --Robert Funas, "Corn is King!" (1886)

Despite the bounty of native wood, field and stream, many in Dixie contented themselves with corn and pork. "A man who has corn may have everything,” writes Martineau of what she considered the typical Southerner’s attitude on matters of diet. “He can sow his land with it; and, for the rest, everything eats corn from slave to chick.” These foodstuffs thus allowed farmers to devote precious acreage to tobacco and, later, cotton. Economic necessity trumped biological; the farmer ceded his land to these lucrative but inedible plants. It wasn't uncommon to see cotton or tobacco fields growing to the very doorstep of a tenant farmer's shack.

Recipe for Corn Meal Muffins from Southern Recipes Tested by Myself (1913): "One pint of meal, one pint of flour, three ounces of sugar, two ounces of butter, two teaspoonfuls of cream of tartar, one teaspoonful of soda, one pint of milk, two eggs, one half teaspoon of salt. Sift flour with cream of tartar and salt into a bowl, dissolve the soda in a little boiling water, stir into milk, mix butter and milk until creamed, add gradually the eggs, then alternately the flour and milk, rub the inside of muffin pan with lard. Fill each three-quarters full, then bake."

These cash crops nonetheless came at a grievous price. Southern farming families suffered vitamin and protein deficiencies that left them blind, toothless and plagued by rickets and other ailments. As a result many of them developed pica and would eat clay and resin by the handful. These so-called “dirt-eaters”

Many "dirt-eaters" jealously guarded their sources of clay.

peopled sand barrens and pine woods from South Carolina to Mississippi, where they endured a difficult, often foreshortened existence. Life expectancy in the South lagged behind that of the North,

owing in large part to such a monotonous diet. In an age when cotton was king, all other crops made way. How ironic the Southerner of yesteryear would find it that today his beloved corn has since ascended the throne.