A clear day in the early nineteen-eighties, for example. A man drives past the harbor of the city in which he lives. He sees docked boats, restaurants, children at play, the island sleeping in the distance. Without quite meaning to, he remembers that the island is a prison. And then, as he is a man of some imagination, he imagines something worse: that people are tortured there. It has been going on for a while.

Years pass. The rough sea of the crossing makes it feel far. The swells are huge. The ferry could sink like a stone. Our tour guide, used to it, sleeps on the journey. Soon, in less than half an hour, the ferry arrives. The prison is now a museum. There was and is a pitiful garden along a wall.

Obscene. That is the word, a word of contested etymology, that she must hold on to as a talisman. She chooses to believe that obscene means offstage. To save our humanity, certain things that we may want to see (may want to see because we are human!) must remain off-stage. (1)

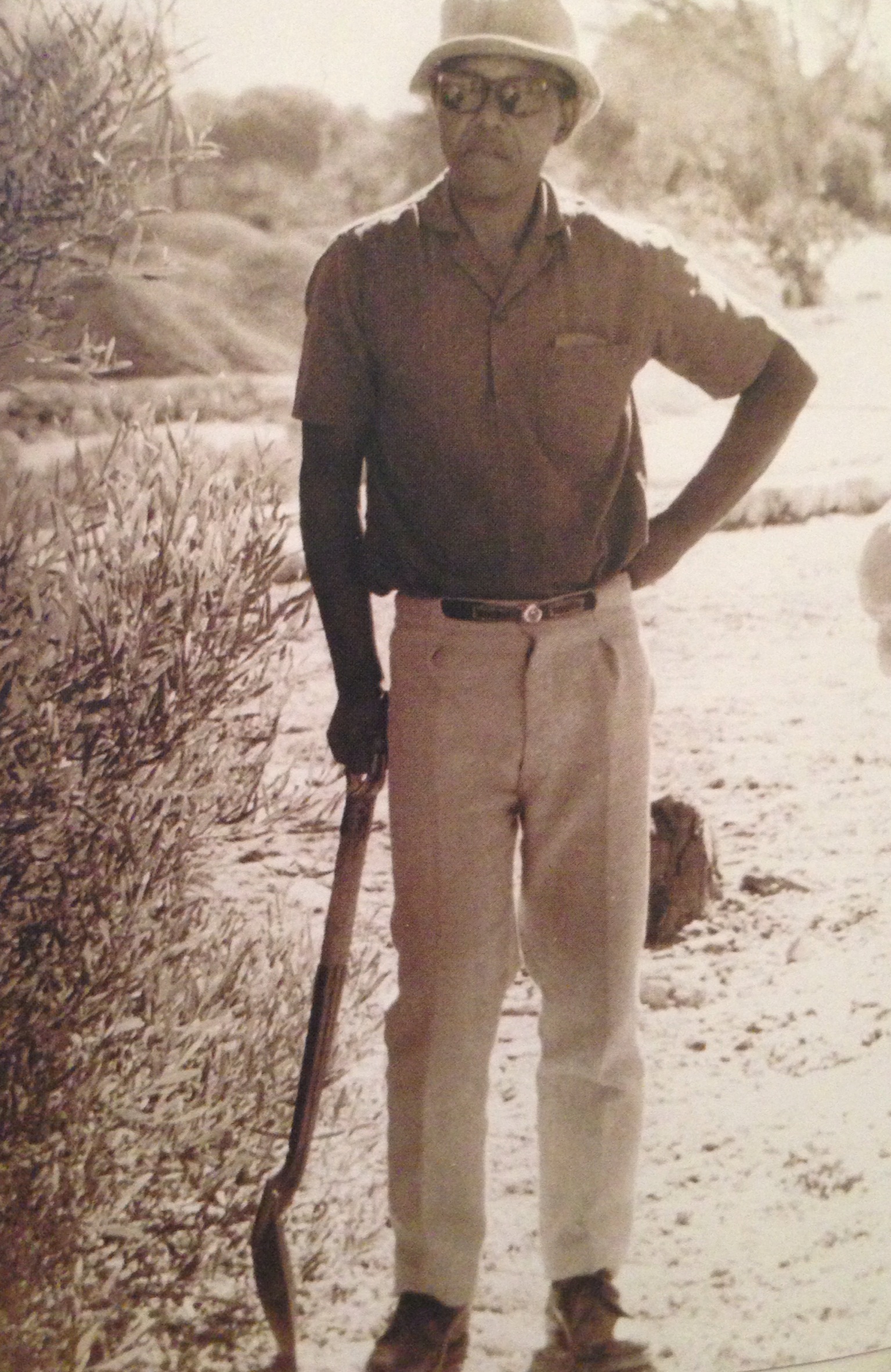

A sunny afternoon, 1977. The torturers have arranged for some of the prisoners to be photographed. They lead them to an arid patch of land (away from their own tiny garden within the walls) and give them shovels. The press is told: this is a garden. A photographer takes a picture and captions it: ’n Gevangene werksaam in die tuin. “A prisoner working in the garden.” The prisoner is not working. He stands erect, faces forward. He wears a floppy hat and dark glasses (when they let him go thirteen years later, he will be unable to shed tears: the limestone quarry will have ruined his eyes). He is a contained fury.

On the island, the tour guide mentions names. Each falls like a stroke of the cane. Sobukwe, Sisulu, Mbeki, Kathrada. The names raise memory's welts. On the other side of the island—the island which is surprisingly big, surprisingly wild—the waves break their heads against the rocks repeatedly, trying to forget. From time to time we see ruined ships.

Twenty-seven years later, the prisoner looks at the photograph. “I remember that day. The authorities brought these people to prove that we were still alive.” Ambushed by memory, the prisoner becomes angry again. He begins to denounce one of the visitors from that day. A handler intervenes, “Khulu (Great One), you know you can’t talk like that.” He won’t be corrected. “No, we must be honest about these things.” The god of his youth is in his voice.

Blacks are allowed in the Company’s Gardens now. You can see them with their families on a warm day. Things have changed (but fewer are the blacks in the fine restaurants on Long Street, two blocks over; things are unchanged). Near the Gardens is the Slave Lodge. In the heart of the Gardens is the monumental statue of Rhodes, his arm raised towards the rest of the continent: CECIL JOHN RHODES, 1835-1902. YOUR HINTERLAND IS HERE. His gesture reads, through history’s lens, like a Nazi salute.

White supremacy has its uses. Because of its great care and its thoughtful strategy, because of the tireless way it hoards its hatred, it is good at making heroes. Mohandas Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr, Desmond Tutu: what would our lives have meant without theirs? No wheel moves without friction. Without the obscenity of white supremacy to resist, they might have been mere happy family men. Nevertheless: Whoever was tortured, stays tortured. Torture is ineradicably burned into him, even when no clinically objective traces can be detected. (2)

The island migrates to other places and the torturers diversify. But the island is never far away. Occasionally, it leaps into the mind of a woman as she goes through her day during the twenty-first century. A man, somewhere, is jolted awake in the middle of the night by things he knows are true. If the island's physical distance is a little greater now, its moral distance is not.

The prisoner finally dies. The torturers take a moment to praise him (to praise themselves). Then they return to work.

Notes:

1. J. M. Coetzee, “Elizabeth Costello,” 2003.

2. Jean Améry, “At the Mind’s Limits: Contemplations by a Survivor on Auschwitz and Its Realities,” 1980.