The new Venetians were coming forth to the setting sun and the approaching fleet.

They came out of gutted houses and gutted banks, they came on rickety rafts and gondolas through the canals. They clambered out of manholes into the light and they stopped their work in the garden but they did not put down their tools, the hoes and spades, the poles and rakes, they carried them across the square to join the eddying flood of prisoners that gathered by the hundreds, the thousands, those who do not break into a nerve’s run but walk steady through the bent and buckling streets. They took those tools and those fingers and they wedged them under the stones of the square and they pried them out, one by one, clean and ragged. They tore the stone shutters from stone window frames, and they swung the rods of iron into the glassless space, splitting the air that divides a square from a room, the iron cracked against the frames of Istrian stone from which the wood had been torn to be burned and which now were only lime hollows and they hit that stone until cracks grinned and ran, raising cloaks of dust and still they swung til tiny slivers of city became chunks, and the scabbed barrier between frame of stone and walls of brick burst apart in their hands, breaching the line and pieces of building came free like pieces of street do, brick and column, balustrade and cornice, capital and relief, and these they picked up one & one and carried them through the focused mob, and they threw it all into the canal.

They hauled from those gaping homes the little furnishing that remained, the mattress on which fluids had set into clouds, the three-legged chair, the toppling Ikea desk, the cutting board, the shower nozzle and the dry faucet and handfuls of carpet saved for emergencies pants worn through to oblivion thumbed books and clutched blankets and half-burned blankets and books, and bowls to be filled and the scraps without name, the grey jugs, the green bottles, a thousand rag and bone things, they brought them forth and they threw it all in the canal. Forth any and all on which hands could be laid, in the abandoned cafés and stores, restaurants and repair shops, out came the drill press that did not spin, the laptops set blind for years in their neodymium stupor, the cold oven doors, ice cream machines dripping stalactites of dust, the dumb microwaves and unanswered phones, his electric shaver rusted through, the meat slicer without motion or meat, the dish washer and the clothes washer, hair dryer and clothes dryer, vibrator and door bell, cathode ray and neon sign, all, all that without power was only weight and toxin and time, and they dragged them out into the light and they threw them into the canal. And the refuse that choked the water packed down beneath its own sighing weight, the incompatible angle formed between road & ceiling, bidets & drapes, tree & coffee maker, the junction of a tricycle & a hammer under a busted gambling table, joined between by sodden books pulped into mortar. The angles compiled and created new gaps between them and the mass of matter closed those gaps, crowding out the water, until the ruinous heap grew to crest the level of the canal that had run slow and loose through the city, and they did not halt, they did stop tearing and carrying, smashing and tossing, wrenching out of obsolescence and onto the wall, & it was now a wall, made of the same city through which the passage it denied had once ran.

They were barricading the Grand Canal.

In the turbid water swam scores, who filled their lungs and went under to stare with fishy eyes at the foundations. They dragged busted benches down and wedged them amongst to buttress the base, checking its tension and tuning the mess, setting fail-safes so no one point of contact between two objects was alone responsible for the form’s load-bearing but that the static collapse cradled itself into deeper density.

Through the water echoed blurry the slaps and shoves and rasping nails of six hundred hands as they took out the western wall of a Prada shop. It broke like a burst wave onto itself, its upper stories rushing downwards into dissolute hunks and beneath that weight fell the bodies connected to eighty-four of those hands but those who did not fall picked up the cement and brick, light fixtures and steel beams, the long-thighed mannequin long stripped bare, and hurled it all onto the barricade and so too they did the bodies crumpled into death beneath the store’s ruin, they gathered them up in their arms like wet laundry and they brought them there too and they laid them on top, and there was more added on top of them, because the heap was not a thing that death could stop, but at first at least, the drinking fountains and stools, mixers and pebbles were not tossed haphazard on the battered ones but placed softer, slightly, soft

A cheer arose. Somehow they had gotten the entire dome of the Madonna dell’Orto off intact. A true feat of uncivil engineering, and they rolled it through the streets as though they had decapitated a giant. Onto the rubbish mound it went.

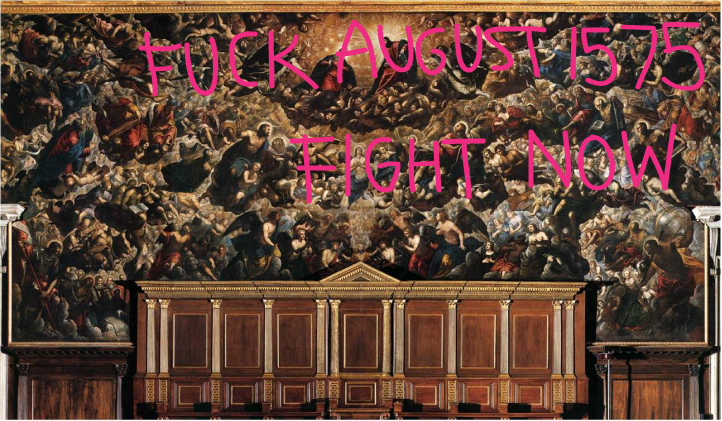

Materials poured in from elsewhere in the city, dragged by tens of thousands of ragged bodies. Fragments of cornices, the Byzantine columns of San Marco, curved iron window grates. Stone vines and stone horses. A Playstation 7. A baptismal font. Twelve baptismal fonts. Crucifixes tossed on like kindling. Tin cans. Porcelain Madonnas and bas-relief saints. Used condoms. Split balustrades, the marble framings beneath piano nobile French windows, the stucco rip-off framings ripped free and borne away. Three stripped Vespas. Twenty-four stripped bicycles. Shriveled reliquaries of martyrs, part and whole, fingers and shrouds. A miracle of an entire stone facade, unbroken as glass, set into place to make the pile a stolen church. A bulldozer. The remnants of a police station. Bread. Underwear. The Porta della Carta and a noseless Saint Marco and Justice and her swords and scales both. Leather purses. Little wood, after all the burning, but the roof trusses of San Nicolo dei Mendicoli made a surprise appearance. Fine Carrara marble fireplaces, half a frieze of winged angels riding dolphins as genderless cowboys do. iPads. Wool. A deep-fryer. Mosaic-graced cement and thousands of pounds of shattered Murano glass. Streetlights. Coradini’s rococo throne. Tremendous gilt frames with no canvas between their shields and tendrils. DVDs. The last four paintings in the entire city that had not been burned: Ernst’s Attirement of the Bride, Giorgione’s The Tempest, Carpaccio’s The Martydom and the Funeral of St. Ursula, and Picabia’s Very Rare Picture on Earth. A recently dead horse. Silverware. The dust of a Tiepolo fresco. Wire. Crutches. The complete sculpture garden of the Guggeinheim collection: Arp, Duchamp-Villon, Ernst, Flanagan, Giacometti, Gilardi, Goldsworthy, Holzer, Minguzzi, Mirko, Merz, Moore, Ono, Paladino, Richier, Takis. Spongebob figurines. Busts and legs and frozen shrouds. Remote-control cars. Fallen putti. Cabbage. Sansovino’s statues of Mars and Neptune, dragged Stalinish through the street. Plastic soccer balls. Shit. Atop it all, a line of toilets and gargoyles flanked two equestrian statues who stared straight out toward the enemy: Ferrari’s bronze Vittorio Emanuele II, astride a rearing horse, his head pried free and replaced with that of a yawning marble lion, and Marini’s The Angel of the City, his idiot arms spread Titanic wide over his chubby steed. His unscrewable penis was removed, as Peggy Guggenheim used to do when nuns floated by, and into the hole was stuffed one end of the entire canvas of Tintoretto’s Il Paradiso, rolled into a crinkling 25 foot rod, unfurling, set smoldering aflame to double the falling sun.

The unmade city towered two hundred feet over the canal, a tsunami in freeze-frame.

From the river below rose wooden ships sunk across the centuries. A two-masted bragòsso gurgled up to the surface, its sàrcia shroud heavy with rotten mud, to rest against the base of the barricade. Five tòpi leapt like sailfish and plopped on without a gasp. A flock of wanna-be Egyptian rascóne, still heavy with sodden grain, and the ponderous trabàcolo, three of them, all gathered steam in their missing sails and rammed thudding in. Their painted eyes stared quiver dumb in anticipation. Four hundred gondolas sprang free from scuttled aquatic nooks and speared themselves backwards into the soft spots of the structure so that their ornamental bowsprits formed goth rows of curving spikes. At last, eleven creaking bùrchii bobbed free. They established the front line of defense while their matching alsàna crested and took the rear and with them too were the horses who once dragged them against the current, the worn shoulders of the nags first buffed by labor and time then shredded by worms and time but they took the ragged lines in their rattling teeth and step by step climbed the swollen obstacle to pull the crafts to join taut the mass.

High above Venice, the prisoners stood, beside the horses decaying and statue alike. From the top, they saw out over the city. They saw roads crumbled into a sabotage of circulation, and other houses falling into rubble to be brought to the war, and thousands of others climbing to sooted roofs to see what else could be broken out, and the gulls circling low, and what they had made and they were deadly silent as they stood and saw and waited.

Then the cops arrived.