I don't like the word literary. It seems to imply some particular formal characteristics, but that implication only allows the term to serve as an alibi for the status aspirations of the people who use it, who want to control its meaning. It's a sort of social tautology that way. The literary is what literary people say it is, which is what makes them literary people.

What's at stake in claiming something is literary is different from claiming that some book is good. What counts as literary is a moving target, but it's not always moving in one direction, toward something objectively better. We are not making collective critical progress toward, say, the perfectibility of prose, of the ability to capture the truth in words and well-formed sentences. Such goals are nonsensical, impossible, though they are implicit in what the literary pretends to be. Instead, literariness is ruled by the laws of fashion; it changes merely to replenish its potency for those empowered to declare what is and isn't literary. Fixating on what is literary actually denies books the possibility of transcending fashion. To evoke a book's literariness is to evoke its transience, not its staying power. It says, this book's only relevant and lasting meaning rests in its capacity to signify the literary.

The idea that the literary strives to be more real or more true is always a smokescreen. What seems real or true in a representation is always just a matter of convention. The conventions are thus always open to challenge for being insufficiently true, and they give way to new conventions that are no more true than what they replaced. As time passes, the old strategies to connote literariness become obvious, arbitrary -- the prose suddenly doesn't seem to pierce reality or challenge our preconceived notions or radically subvert the establishment or whatever it pretends to be doing to catch our attention. Writing that was once so clear, natural, seemingly inevitable and true in comparison to some other fading style, suddenly reads as flamboyant, mannered, craven, overeager to please yet full of arrogant confidence. But the new strategies will prove no more durable.

Any particular literary book is just an occasion for asserting social power, restating one's claim to membership in the literary community, and reasserting that community's gate-keeping significance. In other words, there is good writing and there is literary writing, and any overlap may be entirely coincidental, an incidental accident of fashion.

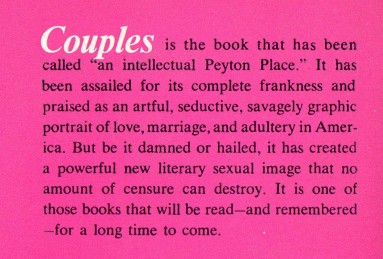

Maybe it would he helpful here to give an example of what sort of usage of literary I'm talking about. I'm currently reading John Updike's 1969 novel Couples, where that overlap between good and literary seems very slight. On the back cover of the paperback I have, this blurb appears:

I suppose this book is remembered, but not necessarily for the "literary sexual image" it crafted. It's more of a historical curiosity, a portal into the late 1960s zeitgeist, tediously tracing the stirrings of aspirational surburban debauchery. And what was once "powerful" and "new" in its language is now sublimely silly. The novel is filled with so many ludicrous, strenuous descriptions of sex that I'm beginning to wonder if Updike wasn't in on the joke. It seems impossible from a contemporary vantage point to believe he was in earnest when writing lines like "A luminous polleny pallor, the shadow of last summer's bathing suit, set off her surprisingly luxuriant pudenda" or "She had wanted to bear Ken a child, to brew his excellence in her warmth" or "If her touch could be believed, his balls were all velvet, his phallus sheer silver." No one needed to censure such images to destroy their effectiveness. Time just needed to pass and expose that Updike was trying too hard, with the sort of effort that is always exposed as a self-consciously literary style ages. Now Couples hardly seems frank or realistic at all; it reads like baroque high camp.

Because Couples' veneer of literariness has aged so poorly, it's obvious that it mainly served to flatter readers, make them feel intellectual while slumming in a Peyton Place. But it lacks everything that makes Peyton Place still a compelling, albeit trashy, read. Couples is so preoccupied with rising above any accusations of vulgarity, naivete, or lasciviousness that it tries to stifle any pleasure the reader might take in the melodrama, bloating it with turgid detail and patronizing analysis.

That's how the literary generally works, as anti-middlebrow critics have insisted since the 1950s. It flatters audiences by offering them false challenges with no stakes. It lets them pat themselves on the back for rejecting pleasure. The literary may no longer be a matter of Couples' "shocking" candor; now it can take shape as arid avant-gardism, formal difficulty for its own sake, genre experimentation, or really anything that the right readers can tell themselves is powerful and new and thus enjoy their own perceptiveness. The literary never lets you forget how literary you are becoming by reading it.

The literary is never a force for positive social change; it's actually the negation of that possibility. It is just another form of cool, and you can't make the world better by making it cooler. That is to say, the literary is just another mystification of the capitalist value form that orients production not toward generating more material wealth but generating distinction. It justifies poverty amid plenty on the basis of effort directed at shadows — in this case the alleged superiority of some socially coded type of language use. A more literary world is one more thoroughly saturated with status anxiety and self-consciousness.

What drives changes in the literary is the need for evolving sumptuary laws of culture to fix people in what seems to be their place, given the existing distribution of power and privilege. In The Ideology of the Aesthetic, Terry Eagelton explains how disavowed value judgments like the literary or the aesthetic work as subtle coercion, letting us experience the process of our being slotted into a social hierarchy as the spontaneous expression of our good taste. "For power to be individually authenticated, there must be constructed within the subject a new form of inwardness which will do the unpalatable work of the law for it, and all the more effectively since that law has now apparently evaporated." The codes and traditions that once made castes explicit — servants wearing livery, for instance — have been tempered, but stratification of course remains. Categories like the literary allow us to feel hegemony as a movement of our superior discernment; the simple joy we get from recognizing the evolving rules of social distinction makes us complicit in sustaining the system and all the inequalities it rationalizes.

I used to think you could salvage the term literary by ignoring its marketing usage and reserving it at least personally for those unique artifacts that appear perfect in themselves. They can say nothing about the people who "consume" them, because they are perfectly indifferent to who reads them. In that sense, they are useless. The sort of works I am trying to describe have nothing to do with the messy business of practical tastemaking and social-boundary drawing. Though it may require a certain cultural capital or habitus to respond to such works, they at least impart no such capital themselves and gain none from being read by the right people. Such books are not cool but seem to be forever beyond the idea.

What books am I talking about? I can't even give a specific example of such a work without disqualifying it by invoking it here; no matter what I'd choose, it would pigeonhole me somehow and turn the book into a signifier of my identity and status. My fantasy of the literary text is a book that can efface its fashionability for the right people. But that's still a description of an ideal disposition toward works that masquerades as a description of the works themselves. The literary never really refers to books but to readers. The reader who purports to be beyond the literary may be the most literary of all, claiming the perfectly camouflaged cultural capital whose value therefore can't be questioned.