I'm pleased to welcome back Alana Massey as a guest blogger—and with this inquiry into how Soviet life shapes the reputation of Eastern European women today, you'll be even more pleased. A graduate of New York University and Yale Divinity School, Alana has seen her work published at The Baffler, Religion Dispatches, Nerve, Jezebel, xoJane, Forbes, and more. You can follow her via her blog, Oh It's Just Awful, and Twitter.

____________________________

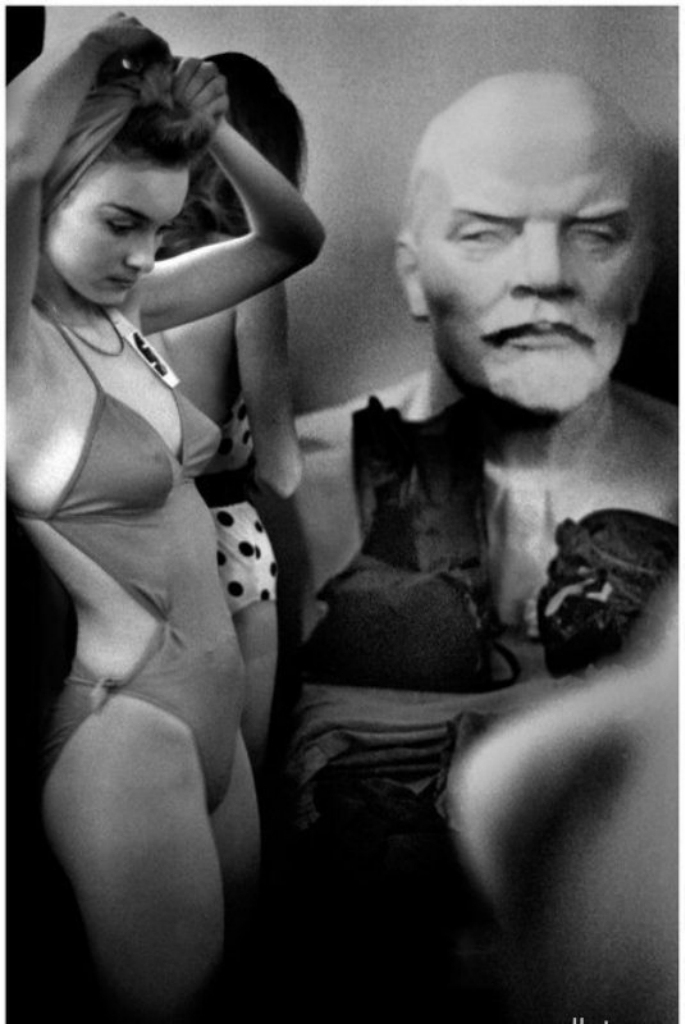

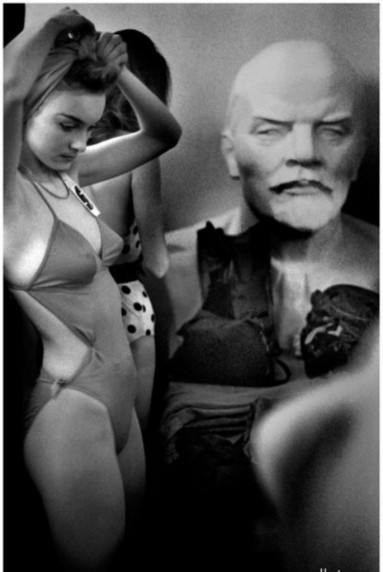

The first Soviet beauty pageant.

Next to the Vanguard Theatre in the West Village, there is an unremarkable-looking salon that appears to be a single room devoted to manicures and pedicures to passersby who have never had a service at Spa Jolie. But ascend the narrow staircase to the second floor and the salon is revealed as a labyrinth of rooms and corridors for every imaginable beauty service performed by a staff primarily composed of Eastern European women. While many workers I’ve encountered in the cosmetic service industry are in a constant state of doublespeak over how pretty I am but how desperately I need a particular beauty treatment, I’m always pleasantly surprised when Spa Jolie staff upsell with no-nonsense pitches like, “Do it. It will make you look better,” or, “It will make your boyfriend very happy.”

A combination of my first name, my bone structure, and my chosen neighborhoods has meant that I’ve been mistaken for Russian since my teens. When I’ve replied to Russian inquiries in English, I’ve received responses ranging from a curse on my parents for not teaching me the language of the Motherland to the shocked declaration, “But…but you’re so beautiful!” And while I half jokingly plan for the latter comment to have a spot in the highlight reel I’ll watch on my deathbed, it is undeniable that features particular to Eastern European women are especially valuable in the post-Soviet era in beauty and fashion.

In a beauty culture that simultaneously celebrates the exotic but still defaults to white superiority, women with Slavic features have become a middle ground on which the industry relies to relay their messages about beauty ideals. By the mid-1990s, as young people from the former Soviet Union emigrated westward, the Crawfords were quickly replaced by Kurkovas on runways, with their razor cheekbones and the permanent pout of downward-slanting lips. But even outside of the fashion and beauty industries where only the tall and worryingly thin have a fighting chance, stereotypes abounded about hyper-feminine, appearance-obsessed Eastern European women. And statistics on per capita spending on cosmetics in Russia support these tropes.

This would be unremarkable were it not for the persistent claims, both internally and externally, that Soviet ideology deemphasized the importance of gender-specific appearance in favor of a model where a person’s value corresponded to their contributions to socialist and communist ideals. While part of the phenomenon can be attributed to the introduction of consumer goods to post-Soviet markets, it’s more than a capitalist inevitability that post-Soviet women—who lived in an era supposedly free of rigid beliefs about gender—came to be seen as the epitome of ultra-femininity.

Dr. Yulia Gradskova, a researcher at the University of Stockholm specializing in Soviet gender history, challenges the myth that Soviet women had neither obligation nor inclination to engage in beauty routines because Soviet ideology was focused on non-gendered qualities. Instead, she posits that the simultaneous demands of Soviet values of culture, good taste, and hygiene that were meant to deemphasize the individual’s gender still reinforced the need for beauty practices whose end result was still a consumer-oriented, western standard of feminine beauty. Gradskova writes:

While peripheral areas struggled to introduce ‘cultured appearance’ to everyday practices, central publications on beauty and appearance focused increasingly on developing aesthetic notions of ‘good taste’. Thus, aesthetic, rather than overtly political, arguments were employed to explain the importance of ‘avoiding luxury’ and ‘loud’ styles as part of a discourse on ‘good taste’.

In other words, look precisely cultured enough to embody our ideal but don’t look too ideal doing it. Subtlety, ladies. Subtlety. Yet in the absence of consumer products that made this standard attainable, daily beauty practices became expensive and often dangerous. Gradskova continues, “Throughout this era women had to cope with an ‘economy of shortage’ and ‘making themselves beautiful’ demanded a complex combination of scarce state resources and various forms of quasi-private entrepreneurship.” Many reported great strain on time and finances to secure clothing that was considered attractive but not so appealing as to draw sexual attention. Expectations of aesthetic appeal were essentially an unfunded mandate to the Soviet woman, meaning that many relied heavily on the black market for fashion and cosmetics to complement their home rituals.

While many of their beauty concoctions like raw yogurt and strawberry face creams would find a home on Pinterest today, others were considerably more brutal. A friend’s mother who grew up in the 1960s in what is now Ukraine reported burning off leg hairs one at a time with matchsticks in the absence of razors. Another woman with whom I discussed her beauty routine recalled applying oil mixed with ashes as eyeliner using a crudely sharpened wooden stick. Despite the frequently bitter cold, many women recounted eschewing unflatteringly thick tights for bare legs with a line drawn down the length of the leg to give the appearance of stockings—a practice also common in the United States in times of material shortages, though it was considerably less hazardous in Kansas than in Siberia. Gradskova’s subjects used burning hot tongs, corks, and pencils to curl and add volume to their hair.

But the physical danger of such practices was also painfully complemented by the social and political danger of appearing too feminized, and therefore sexualized, for Soviet standards. (Not that this double bind was limited to life behind the Iron Curtain, as we still see today.) In a discussion of Soviet beauty, Anne Marie Skvarek writes about the pitfalls of being overly involved in one’s appearance: “A woman who spent time doing such things was deemed to be selfish, shallow, and therefore not putting the good of the collective above her personal desires.” The demands for ultra-specific beauty and hygiene standards even necessitated the creation of a state-owned and operated cosmetics company, the Tezhe trust. Marketing materials for Tezhe used feminine models in makeup and expensive fashions, but showed them being examples of productive labor. The “third shift” of beauty work reinforced a woman’s model citizenship, but only if it was done just-so. Soviet women sat permanently on an uncertain line between embodying Soviet state ideals and being active agents against those ideals through overtly sexual manifestations of femininity. A color-enhanced cheek was forever a brush stroke away from turning one of the Party’s good girls into a frivolous party girl. One had to always be just attractive enough for state purposes but never for one’s own personal purposes of attracting mates or simply feeling beautiful for its own sake. The option of confronting state messages that dubiously linked things like tastefully made-up faces to good hygiene was undoubtedly out of the question.

Later decades in the Soviet era saw considerable relaxation in both the messages about gender expectations and around the flow of consumer goods during Perestroika, but messages about beauty were still cloaked in socialist-speak until the very end. The first Soviet beauty pageant was held in 1988, and while the women almost all appear in sexy apparel and heavy makeup, the event’s organizers insisted, “Our event is not commercial. It has an important, socially challenging objective—to rescue women from urbanization, abandonment in the society and to raise the women value in the Soviet society.” Rescue by way of spandex leotard was just the last incarnation of the similar Soviet messages from the 1930s that connected culture and hygiene to waist-to-hip ratios.

It was not until the end of the Soviet Union that more overt expressions of femininity for the sake of sexual attractiveness reemerged. When they did, it was not as much a sexual revolution as a sexual revelation about the long-standing but suppressed desire to be sexually appealing. As cosmetics flooded the market, many post-Soviet women began immediately overcompensating for both product scarcity and for repressed sexual expression. Cosmopolitan launched a Russian edition in May of 1994 to extraordinary financial returns for its publisher as post-Soviet women flocked to its pages for beauty and sex tips. To some, Cosmo represents everything wrong with modern feminine ideals in the U.S., but for the post-Soviet woman it served as a manual for physical self-expression that had been aggressively policed by market and policies for the preceding decades. The following year, the magazine reported on a survey of 1700 Russian women that revealed that they valued their partner’s orgasm over all other sexual experiences. Today, Russian women reportedly spend as much as 60% of their frequently modest incomes on beauty. Gender studies scholar Elena Zdravomyslova writes that Russian advertisements and entertainment continue to be guilty of "‘aggressively sexualizing’ the common idea of women's roles” in a society currently soaked in overt sexism. It is this aggressive sexualization that has made Eastern European beauty both a source of mystery and of appeal to beauty consumers the world over.

During a Brazilian bikini wax at Spa Jolie, I asked my regular esthetician about the DIY nightmares I’d learned about and asked if she had practiced any of them. She laughed and said, “We did all sorts of stupid shit like that.” I joined her in laughter and agreement at how ridiculous it was, somehow missing the irony of identifying such practices as drastic while she slathered hot wax on the most sensitive region of my body primarily for the benefit of a man whose feelings for me were lukewarm. I would later pay a premium for another employee to take a razor blade to the bottom of my feet so that no one in particular could feel the softness of the soles.

In a later moment of more thoughtful reflection, I considered whether the brutality to which women subject themselves for the sake of beauty is a universal experience in a world governed by the male gaze, and if the fixation of Soviet and post-Soviet women on beauty was simply another variation of women accommodating male desire. Brutal instruments like hot wax and razor blades when used in the presence of cosmetology certificates and scented candles are, after all, still brutal instruments. But because the western beauty ideals that necessitate such instruments have persisted more or less uninterrupted, these regimens serve the fairly one-dimensional purpose of enhancing sexual visibility and viability. But to interrupt that purpose as Soviet norms did gave its reintroduction social and political dimensions that often go overlooked when there are easy jokes about superficial Russian women so readily available.

In the case of post-Soviet women, the commitment to hyper-feminine beauty functions simultaneously as rebellion against the paternalism of the Communist state and as a surrender to the patriarchal insistence on almost caricatured femininity. Her exaggerated beauty is both a move to reestablish her sexual self while also working to limit her to her actual sexual agency. Just as the Soviet woman’s beauty sat at the intersection of party ideals and sex appeal, the post-Soviet woman’s beauty represents liberation from one set of ideals only to become beholden to another set. Western fetishization of her beauty—my own included—sees a smoldering, almost aggressive expression of feminine sexuality. The reality is a much more complex web of historical and contemporary social expectations of what purpose a woman serves and how she ought to look serving it. And serving it for everyone but herself.