I am going to be on a panel at the New Museum on Thursday, June 19 about the "sharing" economy, and why that name is highly misleading. Here's the flier for it:

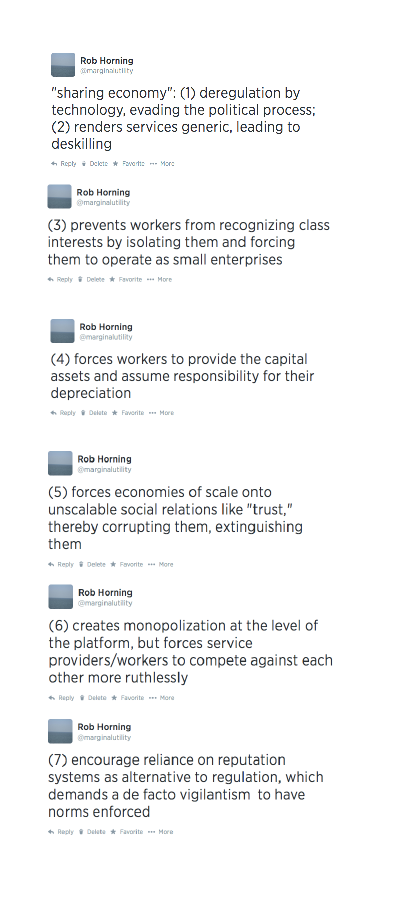

Here are some points about the sharing economy that I listed this afternoon on Twitter:

And below is a book review of "sharing" economy "bible" What's Mine Is Yours that I wrote in October 2010.

And below is a book review of "sharing" economy "bible" What's Mine Is Yours that I wrote in October 2010.

Where money is not itself the community, it must dissolve the community. — Karl Marx, Grundrisse

Like capitalism, consumerism has proven adept at assimilating critiques and adapting to them. In so doing, it cuts away the ground underneath the complainers who don’t appreciate its dynamism. When complaints arose that mass markets forced a stultifying conformity on consumers, the market responded with brand campaigns organized around an ethos of individualism, offering superficial options for customization to appease the desire for distinction.

When critics argued that acquiring goods didn’t necessarily lead to lasting happiness and that accumulation of stuff merely puts us on a hedonic treadmill, marketers like Paco Underhill began to emphasize shopping “experiences,” a bit of rhetorical prestidigitation whereby consumer items became souvenirs of promised states of feeling rather than their source. When the problem was with homogenizing brands and the eradication of mom-and-pop stores, corporations rolled out ersatz small brands and adopted old-timey packaging design to recall the heyday of regional businesses.

When social theorists complained about the hollowness of leisure time predominantly spent consuming and collecting goods, consumption began to be represented in marketing discourse as a creative form of meaning production, with consumers as “co-creators,” using products inventively in off-label ways to enrich their unique identity. When ecological concerns began to be voiced more loudly, the market responded with recyclable packaging and “green” products that offer a moral alibi for our consumer behavior and let us continue our love affair with packaging.

Consumerism’s logic allows it to transform into a form of market research the critiques leveled at it, seeing them as pointing the way to new profit opportunities. The critiques become persausive techniques to reach prepackaged groups of disgruntled consumers, who can be flattered and sold to through marketing that seems to hear them and address their concerns. Hence advertising pitches are constantly being re-tuned to better convey the same message of empowerment of how new innovations really put consumers in charge this time by letting their voices be heard. This customer-service approach co-opts and domesticates any oppositional practices that manage to gain steam, and protects consumerism’s core operating principles: that social relations must be mediated by products; that shopping is the solution to all personal problems; that only branded goods can be useful or have true, broadly accepted meaning; that life’s purpose derives ultimately from consuming rather than making things. It buys off the casually disaffected, preventing them from ever adopting more uncompromising forms of resistance, and it makes consumerism’s hardened critics seem like inconsolable cranks, like poorly socialized cynics who find happiness only in complaining.

This recuperative tendency of the market ought, then, to encourage skepticism with respect to the latest iteration of this process, “collaborative consumption,” which involves various Internet-assisted methods of peer-to-peer exchange and resource renting, as exhaustively described in Rachel Botsman and Roo Rogers’s new book What’s Mine Is Yours. After recapping the history of anticonsumerist criticism, touring through conspicuous consumption, the Diderot effect, the evils of psychologically manipulative marketing, the paradox of choice, and increasing anomie and isolation, the writers proceed to the book’s main purpose, tracing the contours of the redemptive new consumerism, “a healthier more sustainable system with a more fulfilling goal than ‘more stuff.’ ” This new approach to consumption claims and internalizes ideas that have long animated attacks on consumerism, promising to turn them inside out. The new consumerism is not competitive but collaborative, not isolating but unifying, not massified but local, not authoritarian but entrepreneurial and empowering, not wasteful but conservative in the noblest sense of the word.

As Botsman and Rogers detail, the new consumerism derives from the possibilities of mass collaboration and communication offered by new technologies.

The convergence of social networks, a renewed belief in the importance of community, pressing environmental concerns, and cost consciousness are moving us away from the old, top-heavy, centralized, and controlled forms of consumerism toward one of sharing, aggregation, openness, and cooperation.

So if you want to attack the new consumerism, you must not only be a de facto Luddite, but now you also must seem eager to denounce universally cherished ideals like “sharing” and “communities” and “reciprocity.”

In practice, though, the collaborative consumption paradigm merely supplants “more stuff” with more exchanges, as we are encouraged to take every iota of spare capacity we can identity in our lives — any old clothes, unused equipment, any trips taken with free space in our vehicle, a couch not slept on, a garage not filled with junk — and turn it to account by finding a stranger to give, sell, or rent it to. “At the heart of Collaborative Consumption is the reckoning of how we can take this idling capacity and redistribute it elsewhere.”

This commandment to search for “idling capacity” to exploit hardly mitigates the corrosive psychological influence of capitalism; it extends its calculating instrumentalism and market making to every nook and cranny of our everyday lives. Far from redeeming consumerism, it replaces the serendipity of the thrift store, of the sidewalk discovery, with a competitive, rationalized system for distributing goods to eager early birds, to the most persistent users of cutting-edge gadgetry. Whether or not you believe this will increase our society’s fairness is a good indicator of how much you will enjoy this book.

The theoretical underpinnings for the redistribution (not of income or wealth, mind you, just the stuff you already wish you could get rid of) are a sentimental communitarianism fused with a Hayekian faith in spontaneous order. Together these yield a belief that markets can organize themselves to the benefit of small groups of consumer “peers” while manufacturing grassroots surveillance and enforcement systems (what Botsman and Rogers call “trust”) among them to guarantee the exchanges. “We have returned to a time when if you do something wrong or embarrassing, the whole community will know. Free riders, vandals and abusers are easily weeded out, just as openness, trust and reciprocity are encouraged and rewarded.”

Sharing isn’t simply caring anymore; it’s becoming an alienated system for proving your trustworthiness, your willingness to play ball. Best of all, this kind of discipline is implemented at the level of personal relations rather than impersonal markets. In the realm of collaborative consumption, which Botsman and Rogers eagerly anticipate will be powered in the future by “reputation bank accounts” that permit or deny access to the social product, identity is always at stake, making your consumption behavior everyone else’s business like never before.

Were the emphasis of What’s Mine Is Yours strictly on giving things away, as opposed to reselling them or mediating the exchanges, it might have been a different sort of book, a far more utopian investigation into practical ways to shrink the consumer economy. It would have had to wrestle with the ramifications of advocating a steady-state economy in a society geared to rely on endless growth. But instead, the authors are more interested in the new crop of businesses that have sprung up to reorient some of the anti-capitalistic practices that have emerged online — file sharing, intellectual property theft, amateur samizdat distribution, gift economies, fluid activist groups that are easy to form and fund, and so on — and make them benign compliments to mainstream retail markets. Indeed, conspicuously absent from the book is any indication that any business entities would suffer if we all embraced the new consumerism, a gap that seems dictated by the book’s intended audience: the usual management-level types who consume business books, the sort of people for whom Thomas Friedman is a “thought leader,” as Botsman and Rogers deem him.

With such readers in mind, Botsman and Rogers are in the tricky position of trying to hype collaborative consumption by making it seem more or less normal, something in which “regular” Americans might participate without feeling foolishly liberal. “For the most part, the people participating in Collaborative Consumption are not Pollyannaish do-gooders and still very much believe in the principles of capitalist markets and self-interest,” they are quick to remind readers. They reassure us that “Collaborative Consumption is by no means antibusiness, antiproduct or anticonsumer. People will still ‘shop and companies will still ‘sell,’ ” so there is no need to be alarmed. All that’s needed is an image change for the kind of consumerism that’s already happening: “The message that ‘everybody else is doing it,’ ” they advise, “sometimes works better than trying to appeal to people’s sense of social responsibility or even to their hope of safeguarding resources for future generations.”

Such advice suggests that Botsman and Rogers, for all their enthusiasm about people power and communities, believe that social change will be implemented not by the people or even a vanguard of sharing pioneers, but by the guiding adaptations of the business community, prodded by entrepreneurs and wise investors. They will take the fringe practices of activists, intended to actually threaten existing social relations, and make them more “practical.” As Stephanie Smith, CEO of WeCommune Inc., a for-profit startup that generates ersatz communes, tells the authors, “What we are interested in doing is making them an integral part of culture, not a counterculture.”

How will anti-consumerist practices be made safe for late capitalism? The authors refurbish familiar homilies about selling brandable services (community building is their chief example) instead of commodities, and preach how business can “reimagine the larger system” of how they market products to integrate them more deeply into the social life of consumers. They don’t recognize the ubiquity of the branding metaphor as endangering human autonomy or dignity; they merely see it as a force to be leveraged for fresh ends. “In the same way that brands have manipulated us to want more and more stuff by connecting advertising campaigns to deep fundamental human needs and motivations, brands can make us want more of the sustainable values and benefits attached to Collaborative Consumption.”

Thus it turns out that the existing systems for social control through intensive marketing and incubating startup companies render more revolutionary approaches to social change superfluous. We just need better brands and shrewder “entrepreneurial leaders” targeting a reconceptualized set of consumer needs (not things but states of mind and services), and of course, angels supplying them with capital.

But are companies like Zipcar and Netflix really the building-block institutions of a better way of life? Do they move society closer to a place where the standard of living and extent of opportunities are improved for all of us? Or are they just companies looking to profit by performing privatized commons-maintenance duties that government should already be performing on our behalf? In one chapter, for instance, Botsman and Rogers tout the potential of alternative currencies (a subject discussed in this earlier Generation Bubble post), but there’s a reason so many people all around the world want legal tender backed by the faith and credit of the U.S. government, as opposed to scrip backed by the faith and credit of an entity that might turn out to be FlyByNightCollaborativity Inc. Virtual money is simply real money in an obfuscating disguise, or it’s what people are receiving in lieu of the real money that ends up in the pockets of the fake money distributors. (Just try spending Disney dollars outside of Disney World.)

Botsman and Rogers’ championing business as the solution to the social problems business has created is certainly pragmatic, but it feels a bit like surrender, an admission that the institutions of consumerism and their motivational apparatus can’t be bettered, and that they will continue to constitute our lifeworld. The authors can’t be faulted for their unmistakable enthusiasm for mitigating the selfish individualism that consumerism inherited from capitalism’s early days. But their vision stops far short of the kind of transformation that could make “sharing” and “collaboration” into something other than marketing buzzwords again.