The lantern that blew out

left us in the dark

when the mine exploded

and the gods took advantage of us

and demanded some glass beads from us

And since we had no glass beads

we are dead dead dead.

And me I sounded the alarm. I survived

I raised my hands without weeping

or crying for help

and because they were my friends

they let me survive.

- Malangatana Valente Ngwenya, "Survivor Among Millions"

The future is finished. It's finished. The future is finished.

- Marissa Di Tommaso, after the quake

---

As I’m writing this, the search for survivors of the earthquake in Amatrice is still underway, still prying open that slim and obstinate moment of optimism that says the search for survivors, rather than the search for the dead. Sometimes it's rightly named, like with the 10 year-old girl found entombed but alive 17 hours after the shock, and it makes every effort necessary. All the sifting of the dirt, all the shared silence to listen for murmurs, all the dogs who come from afar to smell life through meters of rock. But often, as happened today, when a broken chunk of city is lifted up, the survivor is revealed to not be a survivor, to not have been no matter what the search was called. The moment and its maybe slam closed, and the ex-survivor becomes a contribution to the death toll continually updated in the news.

I loathe the term death toll, how it's trotted out every time a disaster is suffered through. When it was first used, it wasn’t applied to “acts of God,” as claims adjustors and fans of theodicy call such things. It was instead linked to death in the service of a cause, the consequence of taking one or the other side in a struggle whose severity meant death would inevitably occur. According to Michael Quinion

The term has since drifted in meaning and become generic, used without a second thought and available for shitty puns accidental and otherwise, like the Daily Mail title, “Smartphones are blamed as death toll on our roads jumps by 13 per cent”. Yes, a death toll road, yes, how apt. Yet it’s an open question as to whether it makes sense to call the deaths in Amatrice a “toll”, even as casually as news outlets do, given the way it suggests that death caused by gravity, weight, tectonic disturbance, and the material instability of a city is a required blood payment to some thing, some movement or nation or cause, a geological antagonist that is partisan, that cares one way or another, that keeps count: 77 or 78 survivors who do not survive. 120 who could not. 239 who wouldn’t.

There’s obviously nothing new in this way of dealing with disasters, treating them like the measured or careless work of a vengeful god or two. 65 years ago, in 1951, as though working through the lethal Kansas River flood of that same year by displacing it overseas, American newspapers framed the flooding of Italy’s Polesine region in just these terms. When 150,000 people had to be evacuated from their homes and the farming capacity of the region was decimated, burying fertile land under 6 feet of sand, the Chicago Tribune laid the blame on the Po River being “a bad actor for more than 2,400 years.” A strange choice of phrase, as if the problem was that the Po didn’t really sell the role, like it wasn’t method enough. In truth, it wasn’t, and some weren’t fooled, refusing the idea that, as the article put it, “all man’s efforts have been in vain; the winner is always nature.”

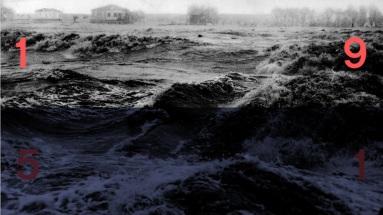

The valley becomes a sea, the Polesine in '51. Still from A Fine Thread of Deviation, with Anne Low

The valley becomes a sea, the Polesine in '51. Still from A Fine Thread of Deviation, with Anne Low

Because as the left communist Amadeo Bordiga saw in that same catastrophe’s pre-history, event, and aftermath, the flooding was no more “natural” a disaster than any other. A flood, earthquake, forest fire, or tsunami may well begin as an unauthored and apparently nonhuman occasion. But it amplifies a set of specific, vicious, and entirely unsurprising social conditions that dictate just who will once again bear the brunt of calamity, even as disasters recurrently get framed as the rare instance of common purpose and national unity. Such generous collaboration and selfless work is, of course, a real and moving thing, but the ground on which it moves, and into which it digs desperate, is long marked by the patterns of what Rachel Carson, riffing off the poisoned robe of Medea to understand insecticide poisoning, called “death-by-indirection.” That indirection routes the blame and damage alike along contours of racialization and class strata that align all too clearly with what is downwind of the smokestacks or built on shaky foundations, what infrastructural maintenance gets put off year after year.

This isn’t speculative in the least, as the 2012 earthquakes in Emilia-Romagna showed. Much of the international media coverage turned its attention to the damage done to the Parmesan industry (200 million euros in lost profit)

For Bordiga, these accidents are never haphazard, even if they can’t be precisely predicted. They are part of a necessary dynamic within capital, a “murder of the dead” (i.e of “dead labor,” in the form of the already made) necessary to spur new output and rejuvenated circulation, clearing the ground for large-scale investment that otherwise moves outwards in search of better returns. The devastation of large-scale war is one mode, an earthquake (or shipwreck, or urban fire) another. In this way, “death toll” may well be the correct and bleak term, because it is a penalty paid, albeit to no subject, cause, or movement, just to the maintenance and renewal of the status quo.

Yet a disaster also points beyond the specific patterns of social power at any given moment, its arrangement of neighborhoods, roads, dams, and electrical grids. It gestures out towards some of the longest-term tendencies of the world order, ones almost too broad to take in a single view until the collapse of function and accumulation makes it possible to see what was at work, even if it means starting with the fragments and lines of failure after the fact.

Platonov on the Po. A Fine Thread of Deviation

Platonov on the Po. A Fine Thread of Deviation

Seeing those requires that we backtrack through a complicated mesh of decisions and actions that can’t separate the willed from the accidental, the technical from the social, the economic from the ecological, the weather from the price of cheese.

a pool of hydrological and seismological organisations cannot be formed, at least not until the great science of the bourgeois period is really able to provoke series of floods and earthquakes, like aerial bombardments.

Here it is a matter of a slow, non-accelerable centuries-long transmission from generation to generation of the results of “dead” labour, but under the guardianship of the living, of their lives and of their lesser sacrifice.

The lesser sacrifice. Flood of the Bisagno, 1970

The lesser sacrifice. Flood of the Bisagno, 1970

It is somewhere between fitting and perverse that Bordiga structures this particular text, like most of his Sul filo di tempo (On/along the Thread of Time) essays of the ‘50s when he roars back into critique after forced silence during the fascist years, around a stark opposition that divides the bulk of the essay under the headings of “Yesterday” and “Today.” Because despite that split, one of the prime contributions of his thinking was to work towards erasing that division, seeing yesterday, today, and tomorrow within an ongoing struggle for survival and quality of life that can no more be answered by resettlement than it can by building apartments from sand. After the flood, he wonders,

So what then if the peasant reclimbs the slope where nothing can ever take root and the very bare and friable rock strata itself does not permit the rebuilding of houses? And the workers by the sea, what will they do? Today they can no longer emigrate like the Calabrians of the unhealthy lowlands and the Lucanians of the “damned claylands” made sterile by the greedy felling of the woodlands which once covered the mountains and the trees that spread over the upland grazing. Certainly, in such conditions, no capital and no government will intervene, a total disgrace of the obscene hypocrisy with which national and international solidarity was praised. It is not a moral or sentimental fact that underlies this, but the contradiction between the convulsive dynamic of contemporary super-capitalism and all the sound requirements for the organization of the life of human groups on the Earth, allowing them to transmit good living conditions through time.

Here, then, is a different search for survivors, a search carried out by those who do survive but, in so doing, must scour the transformed landscape, the inland beach that drowns the soil, for something, anything resembling a way of going forward.