KERRY SANDERS: This looks like it might have been some kind of birthday party.

ANDREA MITCHELL: Let’s make sure we don’t…

KERRY SANDERS: OK, Here’s the first picture…

ANDREA MITCHELL: Let’s make sure we don’t…

KERRY SANDERS: … we’re seeing of a child…

ANDREA MITCHELL: Let’s not… let’s not show the child, Kerry.

KERRY SANDERS: [continuing to flip through stacks of photos of children as the camera records] …and I’m sorry, Andrea, this is sort of unfolding live as we’re doing it. So I’m not sure what the next picture is going to be until I pull them open.

- Transcript of MSNBC’s “FIRST LIVE LOOK INSIDE ATTACKER’S APARTMENT”, Dec 4, 2015, San Bernardino

---

To grapple with the histories fractured and heaped by the earthquake, even from afar and even in thought alone, takes time. It resists either consolation or distillation into single examples, the two processes that seem, for better or worse, most needed in the days following a disaster, whether for genuine grief or the attempt to garner clicks. Perhaps because of this, as the search for survivors begins, so too does a search for images to try and picture the particularity of what happened and to narrow it into something adequately human-scale, even if that particularity lies in how it ruins that very scale and those who form its measure. Early on, in the first hours following the quake, The Guardian not only participated in this, as it always does, but also reflected on the process itself and the drive for an iconic image, noting that the photo of the nun – bloodied, propping herself up, looking at her phone, sitting before a blanket-covered corpse – is “likely to be one of the most enduring images of the earthquake.”

The image stings, as it must, but I suspect that it will be enduring for the way it participates in two genres. First, it's part of a mode of photographing the aftermath of large-scale violence and war that tries to isolate moments of pause, the single individual pulled briefly from chaos and mourning into something quotidian and spare. (I’ll come back to this shortly, in terms of what this does for that problem of scale mentioned above.) Second, the image also fits with a particularly, though not uniquely, American vision of Italy as a nation of temporal contradictions, fusing the traditional and the modern, so that the image of a nun on a cellphone – only odd if one has never witnessed nuns obsessed with Candy Crush, as some definitely are – comes to mark this untimely juncture, a life of supposed repose and care thrown onto the new universal of the screen to find out what is happening and if friends are safe.

In a similar framing (but decidedly not sad memory), recall the shattered Virgin Mary statue – horrors! – of the 2011 Rome riot, that photographers made sure to get from every angle, flames lapping away at sedans in the backdrop.

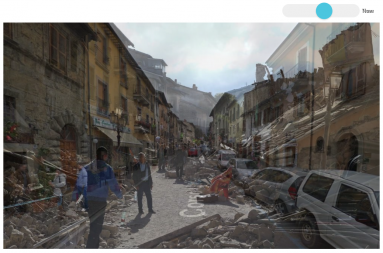

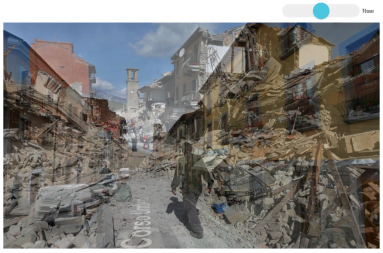

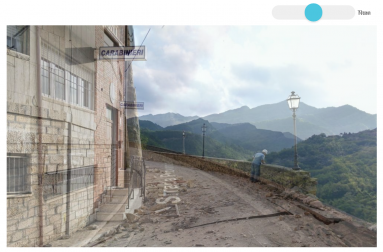

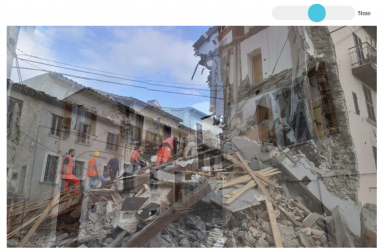

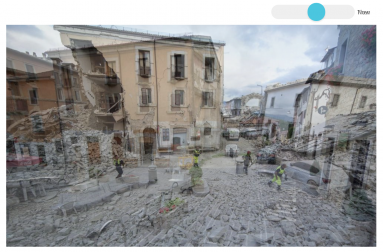

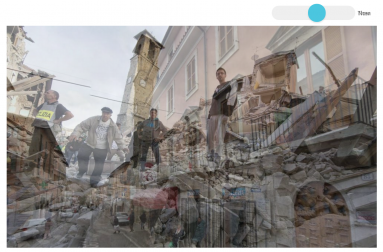

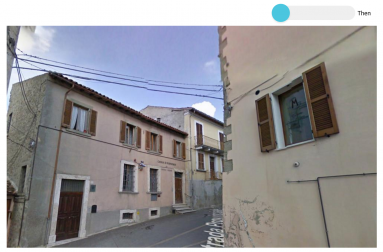

But in the attempt to make the shock available to readers from afar, The Guardian also mobilized a tactic that I’ve never seen deployed quite like this, titled “Before and after pictures of Italian towns devastated by deadly earthquake.” Below the title, and its heading that instructs us to “Move the sliders to see images of the towns before and after the quake,” there are a set of generic, essentially clinical views of roads and buildings in Amatrice and Arquata del Tronto: generic, because the images were not taken by a photographer for the story but are pulled from Google Street View, leaving the superimposed street names (“Corso Umberto I”, “Strada Provinciale”) hovering close over the roads they mark. Above each photo is a slider, set all the way to the left, with a single word to the side:

Then

If we do as instructed and pull the blue button to the right, the word slowly changes. Or rather, it cross-dissolves on its way to reading Now, the words commingled at the midpoint.

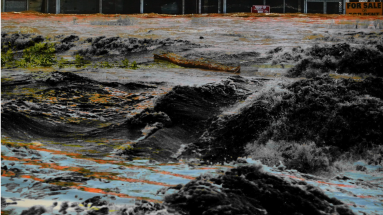

So too the images themselves, as the composite photo gathered by a many-lensed camera mounted on a car trawling the streets of Amatrice bleeds into one taken in the wake of the tremors, where the buildings are broken into shuddering hunks, and the street is no longer clear of pedestrians but full of those standing, staring, and carrying stretchers. If we leave the slider in the middle, the images become impossible compositions, cross-dissolves from an unmade film of the street both whole and not, not a transition but a sudden, shattering cut stuck between frames.

I’ve been staring at these, perhaps in a proxy of return to a place through which I walked a few years ago, and can’t help but feel that something goes wrong in their attempt, other than what obviously went terribly wrong. The kind of energy that Bordiga generates between his Yesterday and Today – spilling out to what came far before and what will persist after until it is taken apart by those who refuse it – is missing in this Then and Now. That absence isn't due to the effort to switch from unquestioned content and the stability of the single image to a problem of form and technique, of possible montage. If anything, that’s where the force of the effort lies, the fact that it doesn’t quite work and never really adds up. But the ease of the slider, the way that it's the same motion one might use to accept or refuse a potential hookup, to unlock a screen, or to scroll along an array of variously colored sweaters, serves to paper – or pixel – over the starkness of the split in time. And this splitmust be first acknowledged and made total to then move past it and tangle with those long-running tendencies that provide the continuity of any contested attempt to “transmit good living conditions across time.”

By contrast, I’m reminded of a startling film, Sicily: Earthquake Year One (Sicilia: terremoto anno uno), directed by Beppe Scavuzzo, itself dealing with a massive Italian earthquake.

In the film, in its very first seconds, the sense of both shuddering shock of the quake and its sprawling time is handled, as with The Guardian’s sliders, by a formal move distinct from what is shown. The film opens onto a helicopter passing above, filmed at normal speed, but when it cuts, it is not to other footage that advances sequentially in time. It is to a still image, a photograph over which the camera will move above and record at 24 frames per second, the only motion its own motion, as if it were itself a helicopter, tracking the lines of the gestures of those depicted, the villagers who point in rage and desolation at the helicopter which should have brought help but did not stop. Its question is plain and difficult: how can one show this sense of time, this thing that is both a sudden wrenching event and a continual process of judgment, neglect, and deterioration? For this film, it is shown as a gap: a profound gap not processed as that impossible Then and Now, to be blurred with no entanglement, just overlay, but rather in the time and ground of waiting itself, between the casual mobility of the emergency aid supposed to come and the territory where it will never arrive. It puts it place an interval that measures the uncrossed air that divides the helicopter that won’t land from the people who cannot wait but who are made to do so all the same. If ever I’ve seen a refutation of the idea that formally disruptive or innovative techniques are somehow elitist and counter to the political potential of art, this is it, in all its ugliness.

This doesn’t happen with the sliders. I don’t want to flatly castigate such an effort that tries to share with others afar some sense of how the unthinkable but inevitable came to happen. It would be easy and wrong to simply chalk it up to a gimmick for clicks, because I don’t doubt that many of those involved felt the awful gravity of what was shown. Moreover, to measure a brief attempt in the midst of an unfolding catastrophe against the critical frame developed by Bordiga, arguably one of the sharpest writers of the communist left, would make little sense, if only because the time and thought put into each diverge so obviously. Still, I want to insist that there is an aspect of these sliding dissolves we need to understand and be willing to refuse, because it goes far beyond the imaging of disaster to face an entire mode of navigating our worlds through shared images.

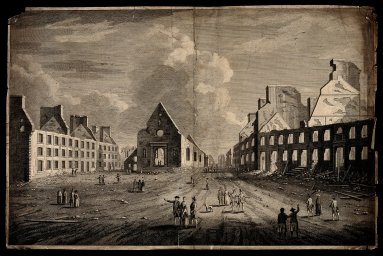

Another example from the archive of Italian photos of Italian destruction can make this clearer.

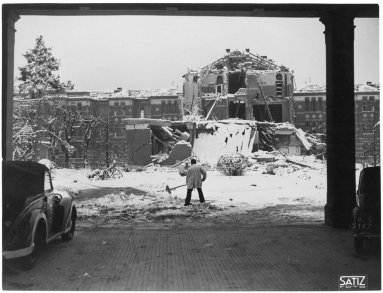

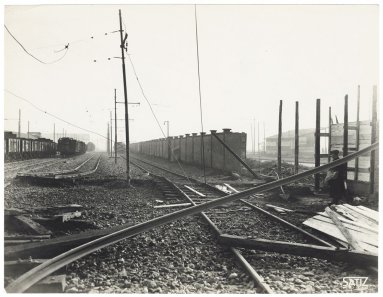

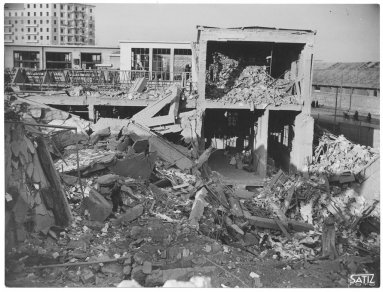

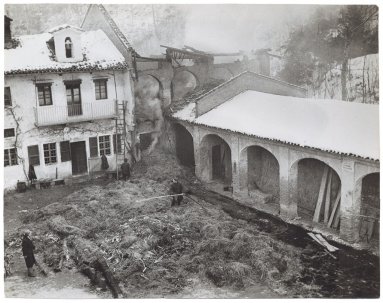

The track survived the bombing, but the explosions tore holes in the hull of the building. Here, the light falls through the silted air to point from newly open sky down to a single figure standing apart from a group in the distance, leaning on a cratered column, looking back at us. Like the photo of the nun, the photo and its brief moment of solitude hurts. But when you look through the other images made of Turin bombed, it starts to look less singular.

In these photos where we confront violence done to buildings, and the implication of what it did to any within or beside them, the figures always stand alone. Sometimes there are several in a single frame but when they are simply looking, they do not stand together. There is no hand placed on a shoulder.

When an action is being done, the rule changes, and a group is shown, putting out a fire or cleaning up the bricks.

And at other moments in the imaging of Turin, when the bombs are long in the past, groups are not just allowed but demanded to bolster the way that industry sets its sights on the city.

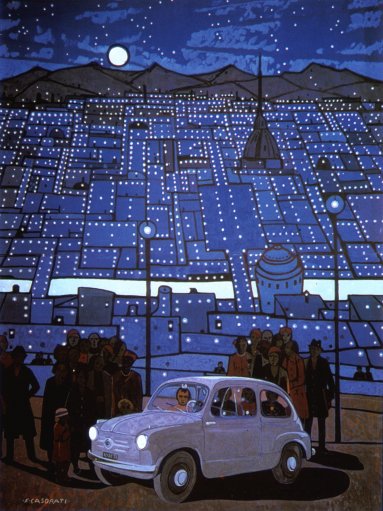

In a Felice Casorati mural commissioned by Fiat ten years after the war ended, figures stand together, clustered around the car whose fluorescence lights their faces. Behind them, Turin is laid out like stars or ghost food, its perspective broken and canted, hanging in the balance between moon and Cinque Cento.

The stellar form finds itself repeated later. In a promo film of the postwar boom, the company will describes itself as a “Fiat constellation,” its capital sites blooming down the peninsula in tiny fires.

But in the photos of the ruined cities that were to enable that ignition on the back of migrant work, there are no such swarms to be seen. When it comes to contemplation, a single figure seems to be required: a yardstick to measure the damage, a model for how to see solemnly. An impossible privacy of feeling, closed frozen in the sight of what had been sighted from above and transformed. This is a task given to photography, not to moving images.

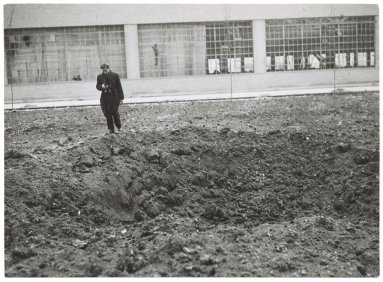

In one photo, a man stands in a field that had no contour and now has a crater. There is no before, no then. Only after.

In another, the photographer himself is shot beside the crater, camera in hand, an operator made into image, alone on a world made moon.

---

It is this sense of human scale that most misfires in the Then and Now sliders, with an effect that would be comic in a different scenario, as giants stride up the streets and dwarf vans, lumbering past the crooked clock tower. In others, the effect is more precise: the body of a rescue worker dissolving into place to peer over the newly ruined wall of a cliff. But this friction and failed match-up is what ultimately haunts these photos. It arises because they are joining two incompatible types of image.

The Now photos are conditioned by the disaster itself, only taken because of what happened and the people that move through it. This is the principle that determines this street rather than that street, the image condensed around these actions, so that the angles the photographers seek come to lack the axial plainness of Street View. They are photos of the absolute breakdown of daily life, only grounded by those doing what they never wanted to, in the way that those photos of bombed Turin sought a human frame for what otherwise had no sense.

The Then photos are fundamentally different. They are images made within and for a project of total functionality, a project of projection where the navigable cartographic grid of coordinates encompasses all. Their aim is to let nothing be unmappable, to stamp a street name onto every nook of the world and promise that you can say, OK Google, take me to 13 Corso Umberto, no matter where you are, and know that it can be done. They aren’t without people and small particularities, but the people are always incidental. The same angle would have been taken no matter if they are present or not, no matter what they are doing. A human is an accident and a bystander for these images, photographed just because they happen to be there, as they turn to watch the car roll by with its many-lensed and mirrorless satellite of a camera on top. If it recorded audio, there’d surely be at least one, OK Google, fuck off.

There isn’t audio, at least not that Google admits to having recorded, but to treat the Then photos as single, still images wouldn’t be right. As the oddness of the slider dissolve makes accidentally clear, they are cinema stills, frames that only make sense within the sequence that surrounds them. For much of the twentieth century, an apparatus that took a continual set of photographic images at mechanically determined – and later, as in the case of the Google camera, digitally determined, with an electronic rolling shutter – intervals would be shown as moving images, as film animated by a second machine that restores the motion both of the camera's displacement from one frame to the next and of all that is recorded in its view.

Paterson, 2011/Polesine, 1951. A Fine Thread of Deviation

Paterson, 2011/Polesine, 1951. A Fine Thread of Deviation

More plainly: the Then photos are meant for a world in which earthquakes do not happen, in which nothing is lost that can't be fixed in post and all gaps are problems to be solved by the same procedure, just smoothing the cracks. In joining the two images this way with the slider, overlaying an already multiple fragment of corporate cartography with something taken later in that location to mark the scrambling desperation of those amongst the waste, these pre-existing street views become crime scenes in waiting. The everyday becomes prelapsarian, the calm of quotidian commerce waiting to be ruined, waiting to be laid alongside and over its downfall. So every street is made into a Then, a precursor and template, rather than its own Now, the way that when someone commits an act called terror or is killed by cops, all their past photos are sifted through, as if the piled debris of a life, and are judged suspect in turn: was it visible in this? Was the t-shirt a tip-off? Look at the hand, how it clenches. A fist? Is it raised? Do the fingers seek to curl? Was the smile wrong? Did it promise violence? Is that a laugh of laughter or a laugh of inconsolable solitude?

Yet unlike the photos we take of ourselves and our friends, ones that might later become evidence in the public trial of the past, the images made by Street View's cameras and proprietary software do not and cannot be organized around details or their urgency, around the way the edge of a neck is made bright for a moment by the light coming off the sea and how you will come back to this again and again. Street View has neither tenderness nor forensic impulse. It records some of everything but only enough to the analogue of a lived world that we drive through without stopping or looking back.