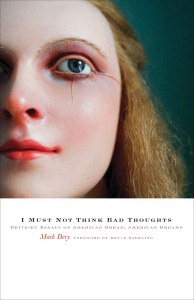

Cultural critic Mark Dery is something of a Tom Wolfe for the BoingBoing set, writing cranky and sneering essays about sensationalistic or offbeat subjects, compensating for the narrow range of conclusions these topics tend to offer with rhetorical excess and a thick smear of knowing pop-culture allusions. In his most recent collection, I Must Not Think Bad Thoughts, Dery writes about, among other things, Star Trek slash fiction, Holocaust tourism, Chick tracts, Lady Gaga's intelligence, and spambot poetry.

Some of the essays are stale because they are dated (feels a little late to be reading about the death of Pope John Paul II), but in general, they are not out to prompt you to think of their subjects in a radically new way, especially if you have already given them any thought on your own (e.g, YouTube Downfall parodies "dramatize the cultural logic of our remixed, mashed-up times"; "Facebook returns us to the adolescent psychology of high school"). The point of the pieces is less to argue for a surprising interpretation than to entertain and assuage readers, make them feel as though they are exempt from the "apocalypse culture" under consideration, surveying it along with Dery from a safe, skeptical remove. Except when he is writing about Nazis — in those essays he is keen to remind us that we are all probably more fascistic than we think.

Dery's style predates the predilection of the current crop of cultural essayists (those operating in the malignant wake of deified DFW) for self-abnegating posturing — explained well by Maria Bustillos in this Los Angeles Review of Books review — which makes reading the book feel very much like a return to a 1990s zeitgeist. This jars a bit with the Internet-driven content he's dealing with. The approach feels out of sync with the meme coverage I'm used to from Hipster Runoff, etc.: Dery's irony is not ambiguous or ambivalent, just sarcastic in a self-righteous Jello Biafra sort of way. His writing conspicuously lacks the disingenuous deference that a lot of online writing adopts, always aware of itself as potential personal-branding copy, potential social-network seeding. Dery's arch-outsider tone is a relic of the time before zines were replaced by tumblrs. (His distance from the spirit of Internet culture is evident in how he wrote about blogs in 2007 as if they needed explaining; blogging is a really "dorky" word, he insists, but it turns out these "blogs" can actually be pretty cool!)

It seems likely that Dery is aware that, in the contemporary context, he's "doing it wrong." But rather than adjust to the milieu tonally, he often becomes overtly defensive and tries to establish that he still gets it by dumping in huffy long-hyphenated-string-of-words adjectives plus what he takes to be relevant cultural references to an imagined straw-man audience. That strategy in itself feels dated, a holdover from the time when the Quentin Tarantino approach to discourse was ascendent and writers tried to bully readers with the unexpected breadth of their allusions. Riddling readers with references, in that cultural moment, conveyed a gangsterish toughness rather than pretension. But the reactive immediacy of online cultural critique, and the ease of information access, has depleted that tactic's sting. You don't drop a reference and leave people feeling dumb anymore; instead you link a reference and everyone can feel smart. Or instead, there are increasingly customized "trending topics" that everyone in a niche responds to, which earns one more attention and cultural capital than trying to invoke something unusual and obscure.

Dery's defensiveness is most apparent in"Aladdin Sane Called. He Wants His Lightning Bolt Back," a tedious rant about Lady Gaga's refusal to be a 1970s glam rocker. After basically complaining that Lady Gaga is dumb and her music stinks, he writes,

By rights I should be femdom'd by the Lady, then thrown to the tender mercies of the butchest of the Caged Heat babes in Gaga's "Telephone" video, you're thinking. I'm guilty of rockism, that unbecoming affliction that causes middle-aged, strenuously straight white guys like David Brooks to subject us, periodically, to a column's worth of mawkish, cornpone about the irony-free pleasures of the real Bruce Almighty (Springsteen, of course)

This passage comprises much of occasionally mars Dery's essays: forced references, the projection of hostility onto an imagined audience of benighted poseurs, the attempt to disavow his own lack of youth by finding a different old square to scapegoat. Why throw David Brooks into this discussion of "rockism"? Why not attack the credence of the rockist critique itself instead of saying "Not me, man. But him." Writers get older and fall out of touch with what striving young tastemakers are pushing, and that's just fine. His defensiveness about it, however, makes me feel like I should be more defensive about it too; it makes me feel old and out of touch, an unwelcome reminder.

At times, it feels like the stakes in certain of Dery's essays is the salvaging of his own edginess rather than illuminating the cultural phenomenon he's examining. These fall into a trap of regarding cool as zero-sum, as something that needs to be clawed back from the clueless people who are claiming it. It's always tempting to want to proclaim that some trendy thing doesn't deserve its attention, but other people's trends are only threatening if and when you acknowledge them, and attacking them only makes them stronger while making you seem like a patronizing curmudgeon. It's not actually a public service; no denunciation of Lady Gaga or, say, Girls will ever give anyone any lasting relief.

Dery is at his best when he finds a clever hook to refresh a tired debate, as in his essay from 1997 that wonders if 2001's HAL is gay and uses that question to explore questions of artificial intelligence more broadly, or in his 2005 essay about advertising and foot fetishes. An essay from 2009 cleverly considers the Satan/Santa overlap. These pieces are amusing distractions, indicative of why the book jacket copy calls the collection "a thrill ride." One can have a fun few minutes reading, and when it's over, the disorientation only stays with you for a short time. I found myself enjoying and then immediately forgetting most of this book, which I don't mean to be as much of a backhanded endorsement as that sounds.

Still, I wished the book better lived up to its namesake, one of my favorite X songs.