Fine is dignity, elegance, class. Fine is edges that manage to be clean yet soft. Fine is a low, respectful whistle emitted under one’s breath. Fine is manners, fine is taste—but if she’s so fine, why is there there no telling where the money went? Fine is the root of refined. Fine is delicacy, fine is restraint, fine is thin. Fine is balanced on the palate, hints of tannin and leather, aged in oak barrels. Fine is please and you’re welcome—and, depending on who’s speaking, wham bam thank you ma’am too.

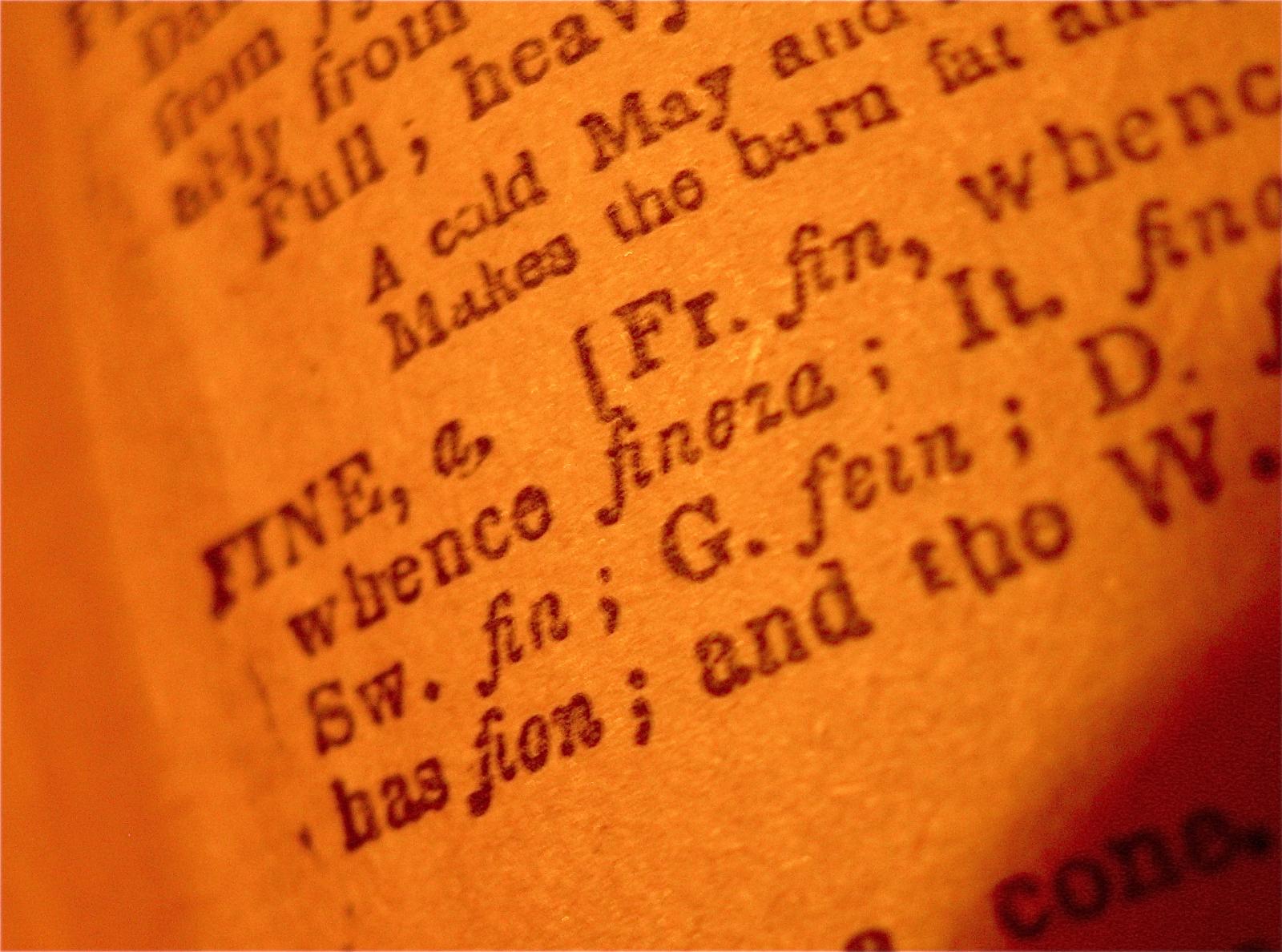

Fine—unblemished, pure, of superior quality—stems from the Latin finis, meaning end, for once you’ve reached the end you can’t get any better, can you? Used since the mid-15th century to express admiration or approval, it quickly became applied to women’s appearances. From Jeremy Collier’s Essays Upon Several Moral Subjects, published in 1700: “Why should a fine Woman, be so Prodigal of her Beauty; make Strip and Waste of her Complexion, and Squander away her Face for nothing?” First Lady Elizabeth Monroe was repeatedly described as fine by newspapers of the time; a 1798 report of a woman’s travels in France describes une femme as “A fine-looking woman, evidently above the vulgar class.” Indeed, class, refinement, and elegance were tethered to the quality of being fine: A woman in the underclass might be plenty pretty or beautiful or even handsome, but fine? Hardly. Manners and affect of fineness mattered just as much as looks, and occasionally writers would delineate being fine from being pretty: “The elder was a fine-looking woman... Yet no one would call her a beauty” (McBrides, 1898).

It would be a mistake, however, to think that fine is always used with wholehearted approval. Even fairly early on, fine could be used as a double-edged sword. For all the elegance implied with fine, the word can also reek of She thinks she’s all that. When applied homogeneously among members of the same class, fine tends to be a straightforward compliment; in the hands of someone with lower socioeconomic status than the person labeled fine, it can turn sour. That fine little number needs to be put in her place—and the one sneering fine knows just the fellow for the job. “She's so fine that she thinks no one that comes up-stairs in dirty shoes worth speaking to” (1860). “Why, she's so fine she can't eat eggs outen chickens that costs less than maybe a hundred dollars the dozen" (1918). “[S]he’s so fine herself. That sort of a woman always finds her happiness in making some unworthy sort of a devil happy” (1911). And filed under U for “uppity women,” we find this entry from a 2001 Ebony: “There was a time where...all you needed to do was turn on the charm, whisper a few sweet nothings and that fine woman was yours.”

Its appearance in Ebony is hardly incidental. If fine tends to be a compliment when uttered by someone who considers himself to be of equal class to the fine lady, it can also be inverted by someone wishing to create class differences within members of the same group. Historically speaking, plenty of black men have been eager to diminish black women—motherhood may be held in reverence, but one glance at the catalogue of misogynist rap and hip-hop lyrics shows that black women aren’t necessarily held in high esteem by their male counterparts. It was actually a rap song that first alerted me to the subverted use of fine—“She’s So Fine She Can Ride My Face,” by C-Boyd, aka “Mr. Ride My Face.” (Argue all you want for a song about cunnilingus to be a positive turn for women; the lyrics include gems like “I’m gonna take her home if she’s wasted”—presumbly not for a glass of Alka-Seltzer—so I’m sticking with my initial distaste to the phrase “ride my face.”) Then there’s hip-hop artist Akon’s take on fine women. “See that girl think that she’s so fine / I must believe her ’cuz I’m losing my mind / Look like the type that love to wine and dine / But I plan to get it without spending a dime”: Akon may have plenty of problems, but treating this bitch like she’s fine ain’t one.

Yet the turnaround use of fine is hardly the word’s dominant usage in the black community: “She’s so fine, I’d drink her bathwater,” exclaimed a Halle Berry fan in a 1999 Ebony. “‘Damn, all that fine body going to waste,’” quoth a black lesbian of what men sigh upon finding out she’s gay, in a 2005 report in Atlanta magazine of black women living on the down low. Going back to the word’s original meaning—that of class, elegance, and visibly “good breeding,” a fine woman is something to behold—that is, she is something to be seen. It’s an (unintended?) nod to the controversial idea of conspicuous consumption within black communities—that black and Latino populations spend more on visible goods (clothing, cars, jewelry) than white populations of comparable income. It’s been disputed by plenty who cite racial stereotyping (“rims!”) as the root of this theory; the 2008 study that examined race and spending concluded there was something to the notion, and that stereotyping does play a role—that conspicuous consumption in black communities comes from the need to prove one’s middle-class status when you’re assumed to not be middle-class by dint of race. Whatever the truth of race and spending, the prevalence of fine in regards to black women is notable: One of Google’s “related searches” options for the search term “fine women” is “fine black women,” while black women remain absent from suggested searches for beautiful, pretty, cute, and lovely women. And image-wise, none of the top 10 searches for those others sorts of ladies yielded a single woman of visibly African descent—while three appeared in the top 10 for “fine women,” including the lead result.

Hip-hop aside, the sheer number of songs about fine women is initially perplexing. Bruce Springsteen, Jimi Hendrix, Clarence Garlow, The Easybeats, Flash Cadillac, Big Boy Myles, Roscoe Dash—all of these artists have recorded a song entitled “She’s So Fine,” and none of them are the same. Compare that with the single entry of him being so fine (“He’s So Fine” by The Chiffons), and something seems askew—something, that is, besides the oodles of tributes penned to women in general, automatically tipping the balance in favor of fine ladies. For a word that has the potential to be applied evenly to the sexes—after all, men too can be elegant, classy, reeking of quality—the overwhelming number of times fine is tacked onto women makes not only the class aspect of the word clear, but the possession aspect as well. (It’s worth nothing that in the black community, the word appears to be more equitably applied, if things like the Fine Black Men Tumblr and Flickr pool are any indication.) Fineness in women is a good, a commodity; much like the fineness in material goods, in women the quality is something to be detected, pursued, and won over. It takes knowledge and discernment to distinguish something—or someone—that’s fine from its more common sisters. And if you have the skills to make that distinction, why wouldn’t you want to possess so fine a good? The songsters tell us this over and over. Lucky for them, fine rhymes with mine.

___________________________________

For more Thoughts on a Word, click here.