By Caroline Cook

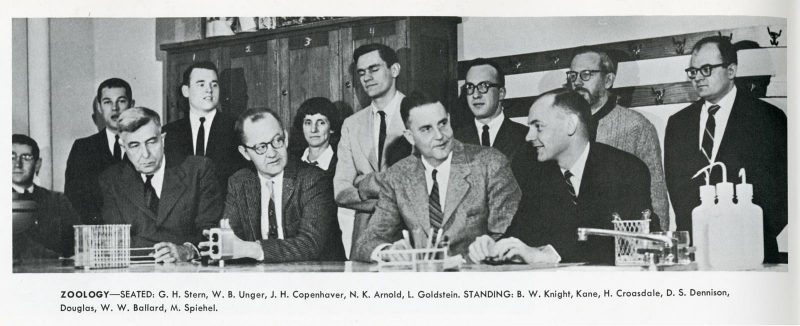

Hannah Thompson Croasdale was born in 1905 and by the time of her passing 94 years later, she had established herself as a force of nature in the science community. She was the first tenured woman professor at Dartmouth College and an internationally renowned phycologist—in fact, she was probably better regarded in the international community than in the close-knit bubble of Hanover, New Hampshire. Hannah Croasdale was a name recognized around the world for her unparalleled contributions to her field. At the time of her retirement from the College in 1971, Dartmouth was not yet coeducational.

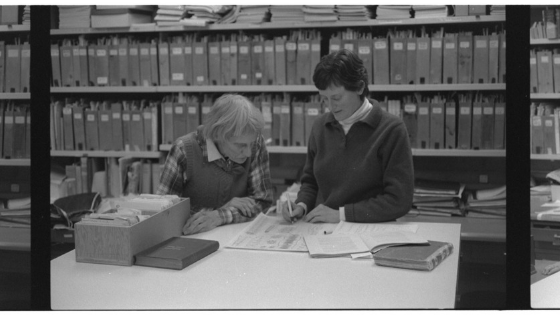

Croasdale had dozens of publications and was responsible for the identification or proper documentation of countless species of desmids and algae. She spent her summers in the ‘20s and ‘30s at Woods Hole Marine Biological Laboratory in Massachusetts, where she collected samples and carried out other duties typical of the unusually gender-balanced community but wholly atypical of the rest of the country at a time when less than 40 percent of bachelor’s degrees were conferred to women. She also taught courses at Woods Hole years before she was permitted to teach at Dartmouth. Before becoming a full professor, she served as President of the Phycological Society of America. Beyond her prowess as an accomplished phycologist, she was also engaging educator, one who could make the most disengaged student vehemently passionate about algae. Near the end of her teaching career, she taught classes in the summer as an Emerita and was able to see the first six classes of women matriculate to Dartmouth.

In all respects, Croasdale was a pioneer, achieving a lot of “firsts” at Dartmouth in her time there. Her presence and perseverance in her field and in her workplace allowed room for the women who came after her. But she is not what we have come to expect from a feminist figurehead. To the awards and scholarships established in her name, Croasdale expressed her confusion at their creation, especially the Hannah Croasdale Award established at Dartmouth that was originally given “to the man or woman who made the most significant contribution to the quality of life for women at Dartmouth.” At the very end of her career in the 1970s, Croasdale was suddenly met with a wave of equality-hungry women who expected a world where they got paid the same as their male peers and were afforded all of the same opportunities.

Croasdale was not the feminist leader that those women might have wanted her to be; while she helped create the space for them to have their debates, she thought they were asking for too much too soon. “I never did anything for [women students at Dartmouth] except tell them to be quiet and wait,” she said in an interview in 1995. “I protested because I’d done nothing. They say now I was an example just hanging on.” While we might disagree with her view of herself, she is right — that’s just what she said to eager women, finally allowed to enroll as students at Dartmouth in the 70s. Be quiet. Wait.

That phrasing would’ve surprised young feminists in the 70s, but it feels even more shocking to hear today. There seems to be a disconnect between the way some feminist trailblazers are remembered and how they viewed themselves. Historical context is incredibly important for explaining why women like Croasdale — women we put on pedestals as icons of generations of young modern professionals — may have tolerated unfathomable treatment. A deeper understanding of their context also explains why these women may not have viewed themselves the way we do.

First, there is an issue with the word “tolerance” because it implies a level of agency Croasdale and her contemporaries did not fully have. To tolerate something is to choose to accept it, or, at the very least, to adopt a conscious apathy towards that behavior. If she wanted to keep her job, or get one in the first place, there was an understood brand of misogyny and sexual harassment that she would confront every day in every corner of her workplace environment. That was the deal.

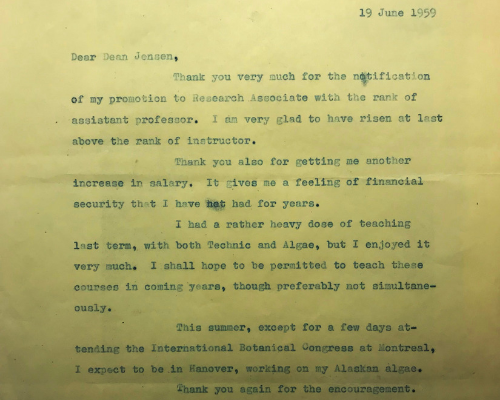

Perhaps it is because of this lack of agency that Croasdale never viewed herself as a trailblazer. She was a freshman in high school when women were granted the right to vote. That fact may help color the anecdotes she told her young female interviewers when she was in her late eighties, laughing about the treatment she had endured. Often, like other women in her generation, Croasdale was blatantly ignored at faculty meetings, avoided in the hallways, forced to share classroom space, and operate without a budget. She claimed in an interview to have made lab equipment for her students using can openers and pantyhose. Croasdale was not expecting treatment different than exactly what she received; the world as she understood it in the 20s and 30s was an unforgiving one. Illustrating textbooks and picking up other odd jobs to supplement her embarrassingly low salary was understood. According to Mary Turco in Strides Toward Equality: Academic Women at Dartmouth College from 1994, Croasdale made around 60 percent of what the average male professor earned in 1959, and compared even to other female professors, she was still around 15 percent behind the national average.

Why did she finally get that professorial status and that all-important tenure when other talented women educators did not? Why Croasdale, the reluctant pioneer?

She had a few strong female role models as a child — her paternal grandmother was one of the first practicing woman physicians in the city of Philadelphia — but perhaps more important was the advocacy of the male allies in her life. Many were powerful men at Dartmouth or in the phycological community who recognized her talent as an educator and advocated for her. The eventual provost at the College, Leonard Rieser, a talented scientist who had worked on the Manhattan Project before arriving at Dartmouth, recognized Croasdale’s unrealized potential. Almost 20 years her junior, he became personally invested in advancing her career. Many letters were written on her behalf that she herself never read or knew existed — letters that argued for her promotion, or that blatantly acknowledge that she hadn’t gotten a raise or a classroom because she was a woman. In fact, it was some of those enchanted students who wrote passionate essays on her behalf about how she alone had sold them on algae as a fascinating area of study. Rieser eventually fought for the creation of a speech course aimed at junior women faculty to level the playing field, as they were receiving disproportionately negative classroom reviews from their students. (The course became so popular that junior men faculty fought for spaces.) Rather than letting the system punish women less comfortable with commanding a room full of men, he recognized the systematic and cultural barriers in place.

In this way, the progress forward that we attribute to one figurehead like Croasdale, was actually the painfully slow advancing of a needle, one controlled by an entire community. But it was all of their actions, not just Croasdale’s, that mattered. Perhaps this is what she meant by “Be quiet” and “Wait”: revolutions do not come by working alone. Women at Dartmouth would have to wait for the tide of male advocacy to turn in their favor. It would come gently, quietly.

Remembering the situations of Croasdale and other women in her generation is one of the burdens that women still benefiting from their hard work carry. Part of that responsibility is asking just how those women wanted to have been remembered. For Croasdale, the people who still remember her are few and far between, though former students of hers — some who went on to become professors of biology in the very same department — will still light up at the sound of her name and describe vivid images of Croasdale, battling arthritis, leading a parade of students across slippery rock surfaces on a summertime field trip. Nothing could stop her, they’d say, from collecting her samples, and Croasdale never was one to watch from the sidelines. She may have been a giant of phycology, a critical cog in a rapidly progressing machine, but she really wanted to be remembered as a passionate educator above all else.

Author’s Note: All archival correspondence is cited by permission of the Rauner Special Collections Library, Dartmouth College

Further Reading

Turco, Mary. 1989. Hannah Croasdale: Portrait of a Woman Scientist, Teacher, and Pioneer at Dartmouth College, 1935-1978.

Chilly Collective. 1995. Breaking Anonymity: The Chilly Climate for Women Faculty. [Waterloo, Ont.]: Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

Hannah Croasdale Manuscript Collection at Rauner Special Collections Library, Dartmouth College

Caroline Cook is a sophomore at Dartmouth College and a writer whose work explores social concepts of gender. She has illustrated and co-authored a children's book based on scientific research, and her work was included in the anthology The Best Teen Writing of 2017.

Lady Science is an independent magazine that focuses on the history of women and gender in science, technology, and medicine and provides an accessible and inclusive platform for writing about women on the web. For more articles, information on pitching, and to subscribe to our newsletter, visit ladyscience.com.