What’s the difference between artistic ambition and pure pretentiousness? When one listens to the Doors, this question can never be far from one’s mind. Yes, the group often does blow open the namesake doors of perception in many a young child’s fragile eggshell mind, but these same minds also tend to reach a point at which they are ashamed at having been so transfigured. Once they break on through to adulthood, they find themselves embarrassed to realize how little substance there is to the Doors’ parables of transgression. The garage-goth organ and the sinewy guitar figures remain alluring, perhaps, but the overriding silliness of Jim Morrison’s posturing, his portentous, overenunciated delivery and his egregious lyrical overreach, becomes impossible to ignore and all too easy to ridicule.

But it’s also hard not to feel somewhat sorry for him. Undermined in his quest to be taken seriously in part by the occasionally solid pop instincts of his band and most of all by his own leonine looks, Morrison sought various ways to sabotage his success, from dropping surreal poetic fragments into otherwise innocuous songs to getting fat and growing a beard (an approach Joaquin Phoenix would later emulate in his own quixotic quest for credibility) to exposing himself while inebriated during a performance in Florida. Lost in his Roman wilderness of pain, he would eventually die of a drug overdose in a Paris bathtub in 1971, at age 27. Ten years later, adding insult to injury, Rolling Stone would help spearhead Morrison’s elevation to the youth-culture pantheon by putting him on its cover with the tag line: “He’s hot, he’s sexy and he’s dead.”

The associated story, by Rosemary Breslin, depicted Morrison as an empty icon of teen rebellion for his new generation of fans: “To these kids, Morrison’s mystique is simply that whatever he did, it was something they’ve been told is wrong. And for that they love him.” Breslin’s thesis, that Morrison was the latest iteration of the eroticized bad boy for mass consumption, seems plausible enough when you look at photographs, but recasting the self-styled Lizard King as James Dean seems to miss the peculiar appeal that his decidedly unsexy music has for adolescents. Conspicuously lacking in subtlety and seductiveness, Doors albums have more in common with those of female-repellent wizard-rock bands like Uriah Heep and King Crimson than with anything you’d put on for a make-out session. They revel in inscrutability, haunted-house creepiness, jarring juxtapositions, and aimless, self-indulgent instrumental passages. Their love songs, of which there are surprisingly few, are generally anodyne and unconvincing, when not arrestingly blunt (“Touch Me,” “Hello, I Love You”). In short, outside of their singles, the Doors often thrived on being awkward and petulantly unapproachable, just like many self-conscious teenage boys.

My own Doors phase began one Christmas when I was in elementary school, after my brother got the double-8-track set of Weird Scenes Inside the Gold Mine, an early-1970s deep-cuts-and-oddities package that seemed designed to cash in on the emerging idea that Morrison was a symbolist-inspired visionary rather than a drug-abusing alcoholic poetaster. Whereas the band’s other greatest-hits compilations naturally focused on their accessible material, this collection featured the Doors' more outré efforts, including “The End,” an ominous and meandering tour of the unconscious climaxing in Oedipal bathos; “The Wasp (Texas Radio and the Big Beat),” an incoherent, semi-spoken-word excursion into the Virginia swamps and the land of the Pharaohs (“Out here we is stoned, immaculate”); and “Shaman’s Blues,” which has an unsettling coda during which Morrison spouts sinister lines like “The only solution, isn’t it amazing?”

These songs were unlike anything I’d heard, except for the Beatles’ White Album — which was fitting, since that record evoked a personage I came to have a hard time keeping separate from Morrison in my mind: Charles Manson. I had already discovered Helter Skelter on the family bookshelf, so when Morrison enthused about how “blood stains the roofs and the palm trees of Venice” in “Peace Frog,” or declared that “all the children are insane” in “The End,” it wasn’t hard for me to imagine him leading a band of drugged-out disciples on a killing spree to set off the apocalypse.

I certainly wasn’t drawn to Morrison because he seemed a cool rebel; if anything, he seemed remote and terrifying, someone likely to shout “Acid is groovy, kill the pigs” as he climbed through the window to murder me. That No One Here Gets Out Alive, the hagiographic Morrison biography by Jerry Hopkins and Danny Sugerman, put forth the proposition that the Lizard King faked his own death and was out there still, haunting the forests of azure as Mr. Mojo Risin, only fueled my fears further.

But by far the weirdest scene of all on those 8-tracks, the thing that frightened me the most, was “Horse Latitudes,” in which Morrison recites — in stilted, stentorian tones without nuance that gradually ascend to incongruously belligerent yelling of Rollins-level intensity — a poem he claimed to have written as a child.

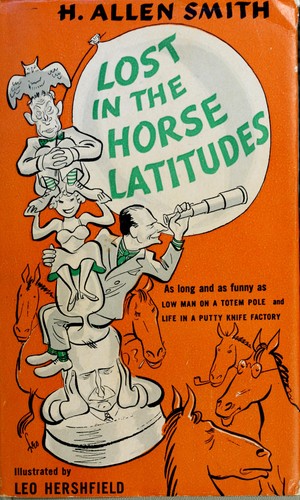

According to Hopkins and Sugerman, young Jim was inspired by a suggestive cover he saw in a bookstore. Over a spooky backdrop of moaning wind and various nautical sound effects, we hear this:

When the still sea conspires an armor

And her sullen and aborted

Currents breed tiny monsters,

True sailing is dead.

Awkward instant

And the first animal is jettisoned.

Legs furiously pumping,

Their stiff green gallop

And heads bob up.

Poise

Delicate

Pause

Consent

In mute nostril agony

Carefully refined

And sealed over.

Though it has some crabbed, superficially interesting diction, “Horse Latitudes” doesn’t stand up all that well to repeated listening. It starts to sound less unsettling and more ham-fisted. But Morrison was clearly proud of the effort, choosing it over his other undecodable poems (eventually anthologized as The Lords and the New Creatures) and persuading his bandmates to put it on the Strange Days album. The band may have believed, along with the label execs at Elektra, that mystical esoterica was an important part of their brand.

But I wonder if Morrison’s fondness for it stemmed from his identification with the sacrificed animals, the expendable ballast. I’m not sure what “mute nostril agony” is supposed to mean, but it seems like a concise description of Morrison himself, who would be doomed to a fate of lashing out against the airhead image the media was conspiring into an armor for him. His career would prove little more than a series of “awkward instants,” whether they were musical moments, pharmaceutical misadventures, or sullen and aborted confrontations with live audiences and the police. (I’ll refrain from speculating on what sort of “furious pumping” went on.)

Morrison seems to have sincerely wanted to launch his drunken boat like a latter-day Rimbaud, but he failed to register the superficial Romanticism in the cultural zeitgeist couldn't really support such a self-image. The Whiskey-a-Go-Go was not fin-de-siècle Paris; the Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour (on which the Doors performed “Touch Me”) was not Le Mercure de France. As much as he may have wanted to will himself into becoming a poet from another age, nobody can make the era amenable by fiat. So he became a sad anachronism.

But this is also why Morrison can still speak to misfits and outcasts who don’t want a sex symbol to emulate but someone who epitomizes the Pyrrhic victory of the will. Like other writers that appeal mainly to adolescents — Ayn Rand, J.D. Salinger, Edgar Allen Poe, J.R.R. Tolkien — Morrison caters to a specific sort of precociousness, encouraging certain baroque ideas about the superfluity of adulthood and tapping into alterity despite his conventional path to fame. And in actual adulthood, you can return to the Doors for a nostalgic idyll about what you once thought the future should hold in store — moonlight drives to the end of the night, supersaturated posturban decadence, cars “stuffed with eyes” in “fantastic L.A,” daring escapes to some soft asylum. But unfortunately, “Horse Latitudes” always lies in wait to remind us which dreams we must jettison first.