No visions of turkey cutlets, mashed potatoes, jellied cranberries, rum punch or pumpkin pie danced in Arley Isabel Munson's head one Thanksgiving morning at the turn of the last century. Rather, her day's duties filled her thoughts as she rose before dawn in a small Indian village.

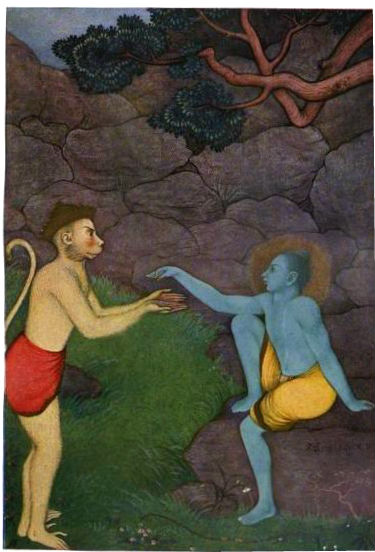

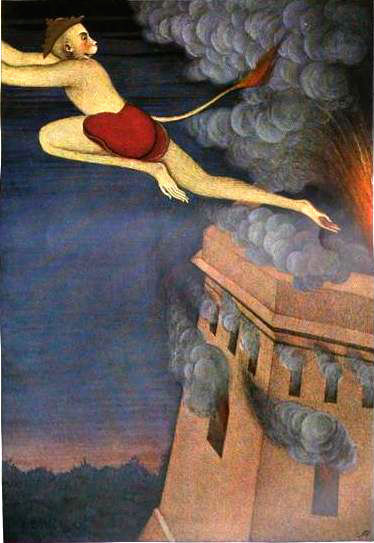

Her arrival there marked the fulfillment of a lifelong dream. As a child, Munson once glimpsed in a mission book an illustration of a Hindu mother tossing her infant into a crocodile’s waiting jaws. The picture so shook her that she vowed one day to practice medicine in India. "I must become a doctor," she would tell whoever would listen, "so that I might save those babies." Her medical school courses she passed with flying colors. Chemistry, gross anatomy, surgery -- nothing proved too difficult. Her residency’s end saw her wielding a expert scalpel. At no time during her studies did she listen to those who questioned her judgment. "Why would you leave the splendid opportunities of your own country for the danger of a far-off land?," family and friends repeatedly asked. In response she would smile, shrug and answer in the tongue of her eventual adopted land, "Kismet! Adrushtam! It's my destiny."

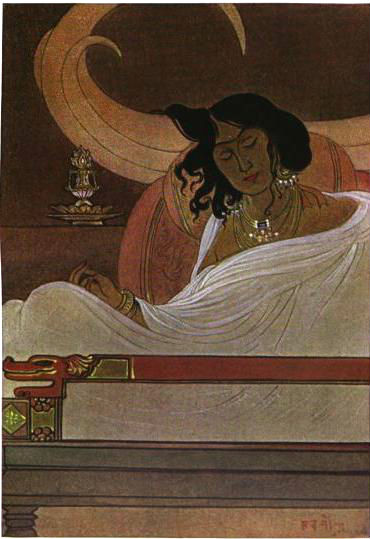

As destiny would have it, Munson settled in a two-room bungalow overlooking a blue lake dotted with white and yellow lotus. And it was there she awoke the morning of her first Thanksgiving in India. As she lay in bed noting her many responsibilities she remarked to herself how strange it was that among the villagers she alone understood the day's significance. It certainly didn't seem like a holiday. The weather betrayed no sense of occasion, the gray sky showing every sign of remaining so. Faded were the blue and purple flowers of her hedgerow; withered, the grass.

Undaunted by the somber morning, Munson dressed, ate a light breakfast and set about her rounds. Thanksgiving for her patients was a day like any other, after all -- and a busy one at that. She paid her first visit to the home of a woman who, believing that Western nurses practiced human sacrifice, refused hospital treatment for fear of becoming the next victim. Unable to convince her otherwise, Munson simply left with her a packet of medicine and wished her speedy recovery.

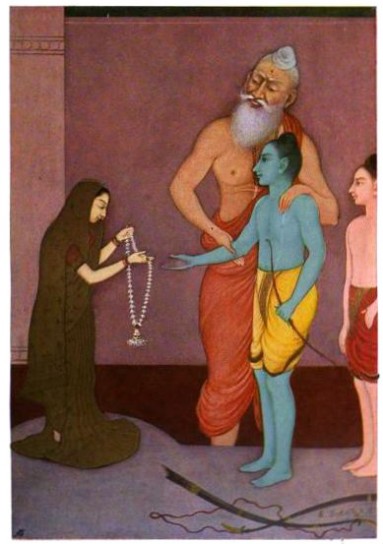

Munson recognized at once that the child bride presented an incurable case. Whatever medicine she prescribed would work only to ease the girl's pain. The girl's mother, scarcely more than a child herself, seemed to understand this, even as she drew her sari over her mouth to stifle sobs. To console her, five gray-haired Brahmin widows stood by. A group of men milled about in silence. A young boy, the girl's cousin, leaned against a pillar. The room had a funereal air. Only a small altar tucked away in a corner against a dirty whitewashed wall betrayed any hope the family might cherish for the girl's recovery. There stood a crudely fashioned red idol surrounded by offerings of fruit, vegetables and small, burning lamps. The idol's head wore a halo of cheap advertising cards and photographs of English celebrities clipped from colored magazines.

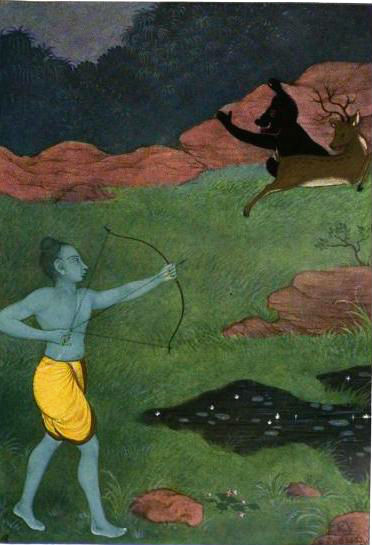

Munson could only leave the girl as she found her; other villagers awaited her help. A young boy whose eyelid had been gored by a bull required her attention, as did a neurasthenic princess whose sole comfort in life was a beribboned pet fawn. There were also an Arab man whose leg bore an abscess, and a woman whose nose her enraged husband had cut from her face.

This particular November day kept Munson so busy that not until evening did she return home, where at half past seven she sat down to a small Thanksgiving dinner of jugged goat with tahku, kahram curry and native vegetables. She picked at her meal wistfully, thinking for the first time of the pies, casseroles and meats that her loved ones stateside had likely enjoyed, and of their laughter and conviviality, too.

But that night, as she lay alone in her cot, she breathed air heavy with the scent of roses and watched as outside her window India's big bright moon rose over the horizon. It seemed a friendlier, more tender moon than the one that shone on her native country. And with this thought she fell into a dreamless sleep, forgetting all about the strange, piquant loneliness of a holiday spent abroad.