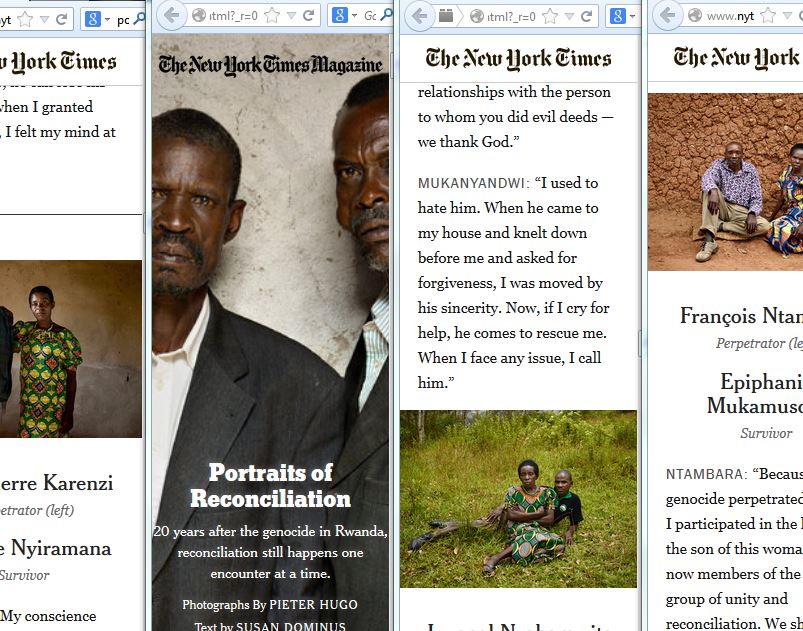

Why does Pieter Hugo's "Portraits of Reconciliation" make us “speechless”? Leave us with “no words”? Why might we find it “stunning”? “Powerful”? “Inspiring”?

I find it disturbing, and I think this is the best thing you can say about it: if these photographs provoke and unsettle you, then Pieter Hugo is doing something interesting with his camera, and he is not simply telling the wish-fulfillment story that victims of great violence can just get over it and move on. The New York Times, by contrast, seems to want to tell the latter story, a story of resilience and human strength, and especially the story of women forgiving the men who assaulted them:

Last month, the photographer Pieter Hugo went to southern Rwanda, two decades after nearly a million people were killed during the country’s genocide, and captured a series of unlikely, almost unthinkable tableaus. In one, a woman rests her hand on the shoulder of the man who killed her father and brothers. In another, a woman poses with a casually reclining man who looted her property and whose father helped murder her husband and children. In many of these photos, there is little evident warmth between the pairs, and yet there they are, together. In each, the perpetrator is a Hutu who was granted pardon by the Tutsi survivor of his crime.

The people who agreed to be photographed are part of a continuing national effort toward reconciliation and worked closely with AMI (Association Modeste et Innocent), a nonprofit organization. In AMI’s program, small groups of Hutus and Tutsis are counseled over many months, culminating in the perpetrator’s formal request for forgiveness. If forgiveness is granted by the survivor, the perpetrator and his family and friends typically bring a basket of offerings, usually food and sorghum or banana beer. The accord is sealed with song and dance.

I want to take a minute to be thoroughly creeped out by this project. This is not uplifting, heartwarming stuff. This is not release, or catharsis. At best, “Portraits of Reconciliation” is terrifyingly willing to place the burden of reconciliation on the bodies of the victims, and then to call it progress when they show, by gestures of intimacy with the perpetrators, that they have gotten over it, moved on. But, for me, everything disturbing about this story gets crystallized in the overwhelmingly gendered narrative these photos tell—all the “perpetrators” are men, and seven of the eight “survivors” are women—while the word “rape” is screamingly absent from the article and the framing.

This omission is glaring, absurd, and obscene. An estimated 250,000 to 500,000 women were raped in the course of the genocide—though who really knows? It could be much higher—and sexual violence against women was as central to the genocidal project as lethal violence against men. “Rape was the rule, and its absence the exception,” as U.N. Special Rapporteur on Rwanda Rene Degni-Segui put it, and it is important to come to terms with that fact: leaving women alive to rape them was as much a part of the genocide as killing them. From the HRW report, “Shattered Lives: Sexual Violence during the Rwandan Genocide and its Aftermath”:

Although the exact number of women raped will never be known, testimonies from survivors confirm that rape was extremely widespread and that thousands of women were individually raped, gang-raped, raped with objects such as sharpened sticks or gun barrels, held in sexual slavery (either collectively or through forced "marriage") or sexually mutilated. These crimes were frequently part of a pattern in which Tutsi women were raped after they had witnessed the torture and killings of their relatives and the destruction and looting of their homes. According to witnesses, many women were killed immediately after being raped.

Other women managed to survive, only to be told that they were being allowed to live so that they would "die of sadness." Often women were subjected to sexual slavery and held collectively by a militia group or were singled out by one militia man, at checkpoints or other sites where people were being maimed or slaughtered, and held for personal sexual service. The militiamen would force women to submit sexually with threats that they would be killed if they refused. These forced "marriages," as this form of sexual slavery is often called in Rwanda, lasted for anywhere from a few days to the duration of the genocide, and in some cases longer. Rapes were sometimes followed by sexual mutilation, including mutilation of the vagina and pelvic area with machetes, knives, sticks, boiling water, and in one case, acid.

If the word “rape” occurred in the New York Times article—if we remembered all the women who were left alive so that they could be sexually violated—then these photographs would look different than they do, I think. We might find ourselves looking at women being photographed next the men they are forgiving—demonstrating with gestures of bodily intimacy that they had been forgiven—and we might be repulsed at the idea that a rape-victim would have to hug her rapist and forgive him, for national progress. We might find the entire exercise horrifying, and not be awed by their resilience, or inspired by their courage.

In the United States, the “victims’ rights movement” has been quite successful in establishing that victims not only have the right to be included in the criminal justice system, but have a right to restitution, either in the form of actual financial compensation or in the ability to take part in punishing the perpetrator. A “victim-centric” approach to criminal enforcement is now an important part of how the criminal justice system “thinks,” albeit only for particular kinds of victims:

once adopted by the Reagan Administration's Justice Department, the mantle of VR was never extended to victims of police brutality or to those whose clothes, demeanor, or skin color earned them harassment or arrest from a habitual police practice of racial profiling. The profile of a victim promoted by this campaign became a White woman or man, victimized by a person of color who was associated with drugs- a highly selective slice of the wide range of victims of crime.

The surviving victims that Pieter Hugo photographed are not called “victims,” however; they are called “survivors.” There are many different ways to think about this choice, and the question is not a simply one. In the United States, for example, one finds a strong moral argument against calling a person who has been raped a victim at all; for many, the preferred term is “survivor”:

We believe that if you have ever been assaulted and you have lived to tell the tale, you are a survivor. You have made it past the assault, and you have earned the title of ‘survivor’ rather than the depressing identifier ‘victim’. It takes courage, bravery, and strength to tell your story, and the Center’s mission is to support that journey every step of the way. We start by calling every man, woman, and child who walks through our doors seeking support a survivor, no matter what their story is.

There is a logic to this, but I don’t think it’s the reason why the seven women that Pieter Hugo photographed are called “survivors”; I think they are called “survivors” because if we called them victims, we might notice that they don’t seem to have many rights as such. Behind such language is a pervasive double standard in how we often think about crime: some victims require terrible justice to be wreaked upon the bodies of the victimizers, while others are declared to be survivors, praised for their ability to forgive, forget, and reconcile. This difference maps onto gender. It maps onto race. It maps onto class. Some victims deserve justice. Some, apparently, do not.

I am not a fan of the actually-existing criminal justice system, because it functions as a form of social control over black and brown bodies, because it serves to protect the interests of only a certain, very selectively defined class of victim, and because it is brutal, stupid, and evil. Which is to say, it is wrong because it is not justice, not really. This is why the injustices of our particular prison-industrial complex are not actually an argument against “justice” as such, precisely because of all the double standards and sadistic repression by which some kinds of bodies are protected while other kinds are punished.

I don’t know what “justice” would look like for Rwandans, but I do know that this is not it:

In the years following the genocide, widows found themselves isolated in remote villages, often the sole survivors living among those who had killed their families. Haunted by memory, too weak and traumatized to earn a living, they were unwelcome envoys from a time that others want to forget, deny or exploit.

Lindsey Hilsum’s devastating “The Rainy Season” is able to include, for example, the fact that “forgiveness” is not necessarily something given freely out of an awe-inspiring reservoir of grace and humann courage; sometimes “forgiveness” is extracted from the bodies of the victimized, who have no choice in the matter, by those for whom the past is better off dead.

“These people can’t go anywhere else — they have to make peace,” Hugo explained. “Forgiveness is not born out of some airy-fairy sense of benevolence. It’s more out of a survival instinct.” Yet the practical necessity of reconciliation does not detract from the emotional strength required of these Rwandans to forge it — or to be photographed, for that matter, side by side. (my bold)

The fact that the “have to make peace”—that they cannot go anywhere else, so must do what they must to survive—is not regarded, however, as a continuation of violence, but is framed as its transcendence. Yet this is a dark, dark image of the aftermath of the genocide, and to see it as anything in the broadest vicinity of uplifting (as most of the commentors do) is, frankly, crazy. The NYT writer wants to emphasize the “emotional strength” of these Rwandan women, but the fact that they “can’t go anywhere else,” that bare survival is framed as making reconciliation a necessity, not a choice, is also a form of violence: they are survivors because, having survived the genocide, they must now survive its aftermath, forgiving the perpetrators, trading physical intimacy for peace. Who is being re-integrated into society here, the perpetrators or their victims? Who is being forgiven?

If the imperative to forgive—and to do so through the uplifting spectacles of the bodies of the victims—ends up producing “survivors” it also erases victims. In place of women who were raped, we get women who survived their families being killed. In place of women being targeted, we get women who were overlooked or let go, who were somehow personally spared. Such people are victims too, certainly, and they might forgive. But we—the uplifted readers of New York Times magazine—seem only to want to forget, to be uplifted, amazed, awestruck, stunned, left with no words. Silence is a woman.