Lenin said there are decades where nothing happens and weeks where decades happen. He could have said there are years where everything happens, and 1977 was a year like that. It was defining for both the United States and Soviet Russia: the former USSR was relatively prosperous, and adopted what would become its last major law of the land, the Brezhnev Constitution. In the U.S. the first Apple Computer went on sale and Jimmy Carter was elected President. Elvis died.

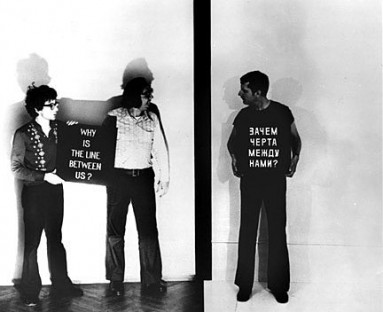

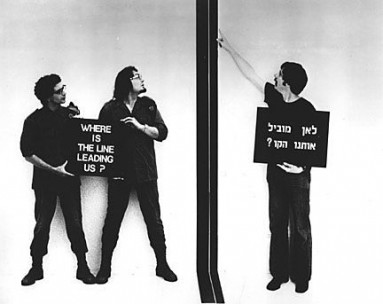

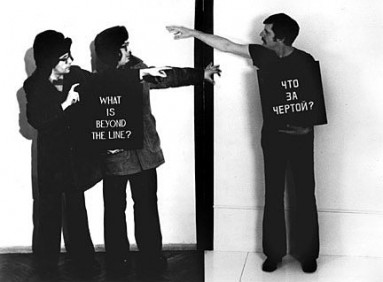

Over the course of the year before their 1977 exhibit, American artist Douglas Davis and the Russian duo Alexander Melamid and Vitaly Komar¹

The impact of this work comes not only from its stark aesthetic simplicity (down to the choice of 'colorless' black & white) but the literalization of a political impasse whose effects seeped into the way ordinary people across geopolitical divides see each other: what's the boundary that separates us? How did it get there? Where will it take us?

I find myself remembering 1976-1977 over the course of 2011-2012²

I note this with some regret since A Separation utterly stands on its own merit as Art, without the burdensome layer of farangi or foreign misconceptions about Iran filed under Politics.

On Sunday, 26 February 2012, Asghar Farhadi's name was called at the podium to the American Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. He approached the stage as A Separation's lead actors Payman Moadi, Leila Hatami, and Sarina Farhadi (his tearful daughter) watched from the audience.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=nT1Xkl6xnsE

At this time, many Iranians all over the the world are watching us and I imagine them to be very happy. They are happy not just because of an important award, or a film, or a filmmaker. But because at a time when talk of war, intimidation, and aggression is exchanged between politicians, the name of their county, Iran, is spoken here through her glorious culture, a rich and ancient culture that has been hidden under the heavy dust of politics. I proudly offer this award to the people of my country, the people who respect all cultures and civilizations and despise hostility and resentment.

I noted two reactions to Farhadi's speech on Twitter:

Heartbreaking that an Iranian filmmaker essentially just had to beg the US not to bomb his country.

This Oscar for best foreign movie cud be a red line³

Instead Farhadi stood right at the edge of that thick black division—if ever you wondered about American political animosity toward Iran, who the U.S. has still not been able to cower into full submission, just watch the lingering camera focus on bellicose Steven Spielberg, a longer intercut than any other B-roll during Iran's first Oscar win—acknowledged its existence, and posed an understated but perennially salient question: where is it leading us?

I note parenthetically that I feel too close to A Separation (whose Persian title is Jodaee-ye Nader az Simin, which literally translates to Nader's Separation from Simin) to offer a close viewing experience. Even though I watched the film a year ago (and described it as a masterpiece to anyone who cared to listen, and let me say it here: the film is masterful and quietly blew away everything else released last year) I think that it should be experienced rather than read about second-hand.

None of the three theaters where I initially watched A Separation were filled to capacity, but that has already changed. Its popularity has been quicker to form than other films exported to festivals; Kiarostami's position as an auteur is unquestioned but even today one would be hard-pressed to call his films 'popular' among Iranians. Sure, there are entangled sectarian lines to cross with a film not made by a government-sanctioned filmmaker associated with the secular left—right-wing provocateurs interrupted the second screening I attended in Tehran, using the thin guise of 'renovations' to interrupt the film without remorse—but the film's real achievement inside Iran is the impetus it gives for a badly needed national discussion around class, especially the North/South economic divide and the devastating impact of accompanying social mores, encoded acts which play themselves out with such gut-wrenching subtly in Farhadi's screenplay.

Leila Hatami said A Separation is a very good film and a very honest film. Is that going to be OK, or at least good enough, for now? Can the American war machine ever grasp its enemies as fully developed humans? Since we are used to managing already lowered expectations good and honest will just have to do.

But Farhadi is conscious that creating a masterpiece is never enough leverage to stand on: you have to allow two counter-posing canvases separated by a semi-imaginary line to face each other side-by-side on the same screen, and ask some difficult questions.