New Inquiry Senior Editor Malcolm Harris talked with artist Alex Rivera. The writer-director of the 2008 sci-film Sleep Dealer, Rivera has been working with drones since the 1990s, when he piloted a small quad-copter called the Low Drone back and forth over the Mexican-American border.

Malcolm Harris: You’ve been a drone fanatic for so long, using them both as subject and medium, and it seems like the wider culture is finally catching up to you. As a very early adopter, why do you think drones have captured the public consciousness in the way they have?

Alex Rivera: The drone is the most visceral and intense expression of the transnational/telepresent world we inhabit. In almost every facet of our lives, from the products we use, to the food we consume, from the customer service representatives around the planet who work in the U.S. via the telephone, to the workers who leave their families and travel from all corners of the world to care for children in the U.S., in every aspect of our lives we live in a trans-geographic reality. The nonplace, the transnational vortex, is everywhere, ever present.

The military drone is a transnational and telepresent kill system, a disembodied destroyer of bodies. As such, the drone is the most powerful eruption and the most beguiling expression of the transnational vortex. The reason it has become a pop-cultural phenomenon and an object of fascination and study for people in many different sectors is that it is an incandescent reflection, the most extreme expression of who we are and what we’ve become generally.

MH: You make the comparison across a lot of your different work between drones and the issue of immigration, but also immigrants themselves. Whether in Sleep Dealer or with Low Drone, what about that specific comparison or metaphor attracts you?

AR: My fascination with drones emerged from a political satire project that I began in the 1990s. I wanted to explore the dissonance I saw occurring between the discourse around immigration — one of xenophobia and increased territoriality — and the discourse around digitality — one of border-lessness and increased free flows. In the ’90s the Internet was in its infancy, but the rhetoric around it was expanding rapidly. Among a whole slew of new metaphors, I was attracted to the concept of telecommuting, because, in its evocation of the idea of working from home, it oddly resonated with the immigrant experience — the experience of leaving home to work, in a particularly acute sense.

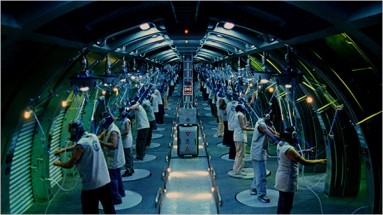

At the same time that the borderless space of the Internet was being developed and celebrated, the government of the United States was building a wall for the first time to separate the U.S. and Mexico. And so there was this dream of connectivity, this dream of a global village, and simultaneously a material reality that borders on the ground were being militarized and fortified. Peering into that contradiction, I came up with a nightmare/fantasy of an immigrant worker who stays put in Latin America and, via the Net, transmits their labor to a worker robot in the U.S. The pure labor crosses the border, but the worker stays out. At first, the idea was meant as a critique of Internet utopianism and the politics of immigration. But over the years it has become a reality as call centers emerged in India, for example, and we began to see the first incidents of service-sector labor being transmitted around the globe. Transmitted transnational living labor was born, or what I like to call the first generation of telemigrants.

Separate from explorations of the subject of literal telepresence, I think, in all of my work, in one way or another, I’ve been looking at transnational networked subjects. The millions of undocumented workers who are physically present but whose political body is denied by a legal regime, occupy a place in my imagination very close to the call-center worker or the drone pilot. The military drone as a traveler headed from the global north to the global south is a kind of mirror image of these other histories that have brought human energy from the south to the north. The transnational space is circular, with flows in and out of the U.S., all of them disembodied and disfigured in complex and fascinating ways.

In my film Sleep Dealer, the main character is a worker in Mexico who beams his labor to the U.S. over the Net and works in construction, erecting a skyscraper in California. The secondary character is a drone pilot who is physically in the U.S. but who sends his energy to the global south in the form of a military drone, expressing his teleprescence in the destruction of buildings. So there are buildings being built up in the U.S. by disembodied immigrant laborers and buildings being torn down in the south by disembodied soldiers. The film is a myth of sorts, simplifying and visualizing these oddly symmetrical global flows.

MH: The drones act as a sort of accelerant — late capitalist cyborg merchant ships that speed up those flows?

AR: Yes, telepresent/transnational exchanges, including the military drone, accelerate and exaggerate already existing neocolonial exchanges. But the new systems don’t replace the pre-existing ones — they exist in parallel and intermingle. And so an enduring neocolonial exchange, like a worker wandering north, through the desert, seeking work, losing their political rights in the process, encounters the 21st century telepresent present when they find themselves under the gaze of a Global Hawk drone, patrolling the skies over the U.S.-Mexico border, inevitably wandering through both American and Mexican airspace. The body on the ground called “illegal,” tracked by a satellite-guided disembodied being, which itself is given legal authority to cross all borders.

MH: So with the automation of both service sector labor and military labor projected abroad, what do we risk being unable to see? I’m thinking of your Cybracero project specifically, the imagined workers you mentioned in Sleep Dealer, the imagined spectral cab drivers. What do we miss when we droneify these kind of service work relations?

AR: I don’t think we even have the vocabulary to talk about what we lose as contemporary virtualized capitalism produces these new disembodied labor relations. We don’t have a way to conceive of what those relationships are, what they could be, what we want them to be. The broad, hegemonic clarity is the knowledge that a capitalist enterprise has the right to seek out the cheapest wage and the right to configure itself globally to find it. I believe that there has been for the past maybe 40 years a continual march in which capital, confronting a labor movement that, with all its flaws, was somewhat successful in lifting wages and creating space for a middle class in this country, has been relocating the nodes of production outside of the legal space — the nation — in which the labor movement has been operating, organizing,

and imagining itself.

Capital responds first with a mechanical move, moving factories outside the U.S., outside the reach of the national labor movement. And then after moving factories out, the next wave is to move information labor out, a digital move epitomized by the iconic call center but that now involves countless varieties of information labor. Amazon’s Mechanical Turk is one powerful example. The remaining tranche is manual service labor — cooking, cleaning, construction, driving taxies, etc. Coincidentally, this last segment of labor that capital has not managed to morph into the transnational space by moving the jobs site into the global south is now largely preformed inside the U.S. by migrants who travel from the global south.

The next stage in this process, and I’ve been told by roboticists at M.I.T. that this prediction (which started as satire) is true and in progress, is for capital to configure itself to enable every single job to be put on the global market through the network and its increasingly sophisticated physical outputs.

In terms of resisting these transformations... If a taxi company has a way for someone in Jakarta to drive the taxies in New York, and it’s going to reduce their costs tenfold, I don’t even know the language to talk about what’s lost for the passenger. And I don’t know how we organize a rhetoric or critique against the idea of more telepresent labor, because the power of the profit motive, of business ontology, is so extreme and universal that its march into every sector of our lives presents itself as a natural truth.

For what it’s worth, the union that serves the subway operators here in New York City managed to defeat a city initiative to replace them with computers by invoking the spectre of security, arguing that a human worker can be helpful in a disaster in clear ways that a computer can’t. Maybe that rhetoric could save the job of our hypothetical taxi driver from a remote operator.

MH: When you’re dealing with a cab driver in Jakarta, it’s not only that you don’t have to talk to them; you don’t have to talk to the cab driver where you live whose place they took. These small externalities that make up so much of interracial or interclass relations don’t even occur.

AR: In discussing the menace of these types of imagined alienated labor, I don’t want to romanticize the present state of affairs. Most of my taxi rides today are experienced with both the driver and myself on the phone, talking to telepresent individuals. Customers at a restaurant today often don’t see the workers — and they’re physically there, maybe 10 feet away — but nonetheless they can become phantoms or invisible presences. The threat that telepresent labor presents — that there’ll be no contact between the person eating and preparing food, that a certain social proximity or contact will be lost — has already happened! The erasing has already occurred.

Returning to the theme of the military drone, a lot of the first round of critique was that they make killing antiseptic or like a video game, or that it’s hyper-alienating for the pilots. But what I tried to depict in my film and what I believe is happening is something not that simple. The drone has produced a third type of military sight. Drone vision is not like the infantry’s vision that sees the opposing forces with their eyes, and it’s not the sight system of the airforce pilots that never really saw what was below while dropping bombs from thousands of feet up, often at night. The drone pilot has a type of vision that no military actor has had before, that of lingering, of observing over extended periods of time, and doing so with absolutely no threat to oneself.

This gaze is unidirectional from the air down; it’s safe, it’s calm, it glides through time. You hear stories of these pilots watching a single house for literally days on end. And these cameras are so high-resolution they can see what’s being cooked for dinner, and they can see if it’s a boy or girl down below. The drone pilot is connected to reality in a way that is very different — not necessarily more or less, but different — than the infantry who’s on the ground with a platoon, whose life is on the line. Some of these virtualized transnational interactions can create new levels of connectivity, exchange, and vulnerability. I’ve been reading stories about drone pilots having versions of PTSD, seeking out chaplains and psychiatrists to deal with the emotional blowback of performing and witnessing these horrible acts so close and sticking around for the aftermath. This is a visual phenomena that no one in the infantry or air force has ever experienced.

MH: Drones, and the drone perspective, have been used a lot in big-budget action movies lately; that’s one place we see it. I know the Pentagon has been involved in shaping the ways that happens. As a filmmaker what do you make of that?

AR: I got a phone call from a guy who was working with a Pentagon research group saying they were using my film in the group because they were interested in drone blowback, drone hijackings, nonstate actors deploying drones, and my film happens to have all that in it. This guy was working for the Pentagon doing this research but was also part of Jerry Bruckheimer’s team. He was involved in connecting the Pentagon to Bruckheimer’s films. The Pentagon typically doubles his budget, so if he has a $100 million budget, they’ll give him $100 million in free military hardware.

MH: Seriously? Holy shit.

AR: Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen was the first Hollywood production with all four branches of the military: Army, Air Force, Navy, and Marines all working on it. What can even be said about that? There’s this extraordinarily complex exchange between the fantasies of war, the process of recruiting, the technologies of war that appear in the films, and the technologies of visualization that get invented by the military and passed down to the entertainment sphere. 3-D graphics get developed in the military, then get used to project films, but these are often action films focused on still other military fantasies, all of it, on screen and off-screen, in many ways written by the Pentagon.

As an independent filmmaker, as somebody engaged with science fiction, I wonder where there’s space for hope in there. I think it’s going to be hard for Hollywood to keep making movies with the spirit of Pearl Harbor or Top Gun if American soldiers are increasingly in air-conditioned bunkers in Nevada carrying out attacks on huts halfway around the world.

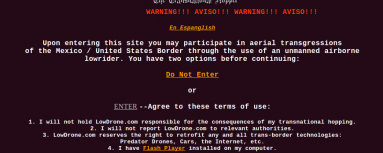

MH: With the Low Drone project, you’re playing with the viewer’s complicity with the piece. You have them agree to take responsibility for the pseudo-legal action of flying a drone over the border fence. Are you concerned with the ways drones isolate us from the consequences of policies they carry out, or is that kind of a red herring and do drones actually force us to confront these questions that already exist?

AR: I’m a member of the Writers Guild, and I recently attended a panel called “To Drone or Not to Drone” hosted by the Guild. It was a gathering of writers in film and television who wanted to learn what’s going on with drones so they can write more accurately about it. The speaker was P.W. Singer, author of Wired for War, and in the question-and-answer session, clearly the writers were troubled by drones and were trying to ask questions like “What do you think about drones being used to assassinate American citizens?” And what Singer had to say was

“You’re confusing the technology and the tactics. The technology is highly precise, and how it’s used against American citizens is a tactical question.” He said we could argue about the tactics but that he was there to talk about the technology. His argument collapsed the discussion. It was only after I left that I realized what a problematic argument it was. Saying “technology doesn’t carry out extra-judicial assasinations, tactics do” is as rigorous as saying “guns don’t kill people, people do.” To Singer, these questions apparently exist in neat boxes: the drone over here, and the ways it’s being used over there. But to me that’s completely false.

Technologies constitute us, they change who we are, what we imagine we can do. That is one of the more troubling aspects of droneification specifically of the military, the way in which the disembodied soldier, the remote aerial drone, can make an invasion into a country not an invasion anymore because no soldiers are going. So we can have drone strikes in countries with whom we have no declared hostilities — not even the casual declarations of recent armed conflicts. It makes what in the old days would have been a risky cloak-and-dagger assassination plot — it’s not like we haven’t always done these things — extremely easy. It changes the cost-benefit analysis. The drone assassin reduces the cost barrier to the tactic. Intellectuals like Singer would have us believe the two don’t determine each other, but it’s not the case. The technology bends the curve of the possible.

MH: But that bending of capacity happens at both ends. When I think of a historical model for an antidrone movement, it would be the antinuke movement. But they didn’t want their own antinuke submarines. Antidrone warfare activists and artists seem much more interested in how they can use those same technologies.

AR: When I talk to people recently I’ve been reflecting that the drone is the first disruptive military technology to permeate pop culture since the nuclear bomb. We didn’t have this kind of fascination with depleted uranium munitions or smart bombs or other military innovations over the past several decades. The drone has become a pop-cultural icon, constantly in the news and culture in ways we haven’t experienced since the emergence of nuclear weapons. But like you’re saying, in the ’50s there wasn’t a big DIY nukes community, not a lot of artists playing with bombs. But there were artists reckoning with the mushroom cloud as an image, lots of storytellers imagining different nuclear scenarios. Atomic language had all these cultural deployments. The drone moment that we live in is a time when all kinds of actors in society are playing with the technology, including people who are directly opposed to violent deployments of drones. So you see the Occupy movement’s Occucopter, for example, or artists like myself building border-busting quad-copters.

The technology is much more within popular reach than nuclear technology ever was. Every technology is invented with an agenda, whether the automobile, the Internet, the television, what have you. These innovations are built with corporate or military agendas, and when they become accessible, they almost immediately become contested sites. You have urban youth morphing the automobile and artists and activists deploying television, the Internet, all these technologies being modified, hacked, and dispatched in innovative ways. The drone seems like, for the first time, to be giving us access to a third dimension, in a sense. We spend our days with our feet on the ground, but the idea that we could build a sculpture that flies, or that you could conduct your own countersurveillance from the air, all seem like organic and predictable developments. Once we get a hold of a technology like drones, artists and activists will redefine and redeploy it.