What remains from dismantled relationships shows just how much power those structures retain.

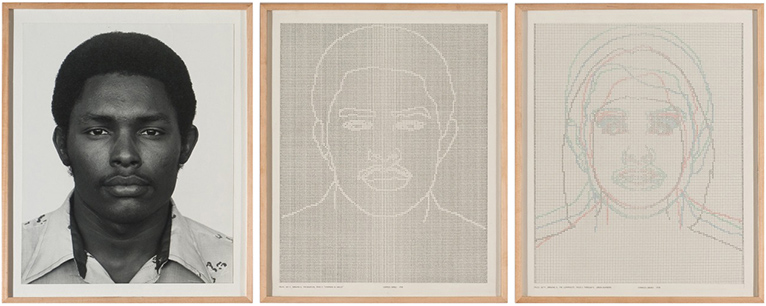

A recent retrospective of Charles Gaines’ work at the Studio Museum in Harlem showcased his longstanding interest in structure, form, and system. Trees, dancers, and faces disassemble into calculated parts. Throughout a long and prodigious artistic career, and in his role as a teacher at CalArts in Los Angeles, Gaines demands careful and precise examination of the structural conditions of experience. His work springs from conceptualism, but its engine is a critique of representation, the urgency of which inevitably stems from his position as an African-American artist in a predominantly white art world. In his work, the subjective and the structural are conditioned by each other, and crucially, they must be mediated by indivisible human intellect and aesthetic sensibility. The divide between two things is never self-evident. For Gaines, nothing, not even the positioning of astral bodies, is taken for granted.

In Night/Crimes, you combine images of reported crime and the night sky. The work evokes both fate and the absence of fate—the smallness of human actions. What’s the relation between the idea of chance and fate?

Night/Crimes was probably the first work where I really focused on the idea of representation. I was interested in addressing the relationship between affect and the image, or how the image produces affect, and what that might have to do with meaning. What I wanted to do was to create a narrative situation where meaning is produced but it isn’t connected with intentionality.

I got photographs of the night sky, photographs of crime scenes and photographs of convicted murderers, and in the piece I combined those three photographs and made linkages between them. For example the subject of the crime itself established the link between the crime scene and the convicted murderer. And that linkage was sort of reinforced by the night sky, because the night sky represents the way the sky looked at the moment that crime was committed, which is to say that if the victim and the murderer looked up at the night sky at the moment of the crime they would see the sky that is represented in the photograph.

These are circumstantial linkages. The murderers pictured in the mug shot-type photographs are not the ones who have committed the crimes you see in the crime scene. Nevertheless, it seems compelling to people to override the fact that this relationship is completely made up. Those causal linkages are determined by pre-existing narratives that we adopt socially and culturally. By establishing that both of them share a particular moment, there’s this compelling narrative suggesting that the sky had something to do with the event. Horoscopes do that. There are certain standard narratives about how physical bodies can affect individual moods, about the relation between the planetary movements and the tides, and about the tides and emotions. I wanted to establish that that causal link was false, in the same way that the relation between the murderer and the crime scene is false. So it’s a general critique of art.

It seems that for you affect plays a role in how we understand events as having causality.

The standard narrative in art is that the affect is the marker or the evidence of an expressive intent. It goes back to the subjectivity of the maker and of the perceiver experiencing the image. The way a painting makes you feel is linked to the subjectivity of the artist. There’s a communication between the subject of the artist and the affect that the art object produces in the viewer. This is a standard framework that’s used to argue how representation works in art or how art works generally.

Aesthetics is the term for a type of experience you have in the world that is not given by the intellect, so aesthetics is part of the general realm of affect. The argument is that this is beyond intellect, beyond any kind of learned process, it connects to a more universal framework, within which art operates.

I want to critique that idea, because what happens there is if the affect you experience is beyond our intellect, then we can’t have a conversation in a critical way about that experience. I wanted to create a situation where the way that we experience the work through our emotions and through our feelings operates within a critical and analytical framework.

In order to make this point, I tried to put together things that are not related and show that when people look at these unrelated things they make a relationship between them and the relationship they make between them is driven not by intellectuality or what can be established critically but the feeling that you produced about that relationship that makes it seem convincing. People think that experience they’re having, therefore, is real.

I want therefore to make the point that the experience that comes together is not a product of causal relationships that actually happen between things but a consequence of putting together narratives we absorb in our lives based on the similarity between things rather than any causality or relationships that we become accustomed to identifying. Yet they still have the same power and the same impact as if those relationships are real.

There seemed to be some kind of implicit critique of the category of crime, which is one of these weirdly tautological categories of causation. I’m thinking for example of stop-and-frisk policies targeted at “high crime areas,” where the areas are “high crime” only because of the level of policing and the number of arrests made there. What makes something a crime is how it’s processed through systems that mark it as criminal behavior. Was that also part of the work?

Crime was the subject of the work, but the critique was not around crime, it was around representation. I was using the subject of crime to address the issue of representation. When that work was first shown and reviewed, most people talked about it in terms of how it dealt with noir narratives in books and movies. And it was because there were certain tropes and certain imagery that seemed to reflect ‘50s mystery movies and so forth. My interest was not so much in making an analogy with noir representation, but to show how social and cultural the production of that kind of representation informs the way we look at things. So it makes sense for it to make a link between a dark starry night and crime because you see it in the movies all the time. There’s no rational relationship. It’s a metaphor. There’s no metonymic relationship between the night sky and crime. It’s a narrative that we’ve come to learn.

But there’s also no exact causal link between particular kinds of death and how we call them murders or manslaughter or accidents.

The law deals with the issue of representation much better than art does. In law they’re not really dealing with what really happened. In law they are dealing with what kind of convincing narrative can we put out there to justify a particular interpretation of an event. There’s a recognition of the gap between what really happened and what we can say happened. There’s even this issue of whether empirical evidence can transcend our emotional and affective relationship with an event. How meaning is formed is a much more complicated process than what establishes evidence at an intellectual level.

The articulation in your work between structure, chance, and choice reminds me of the longstanding discussion about the relation between structuring conditions such as capitalism, the thing that we might call “identity,” and the actual unfolding of individual lives. Maybe that’s contentious already. But my impression of your work is that the structural in some way what dominates. And I wondered, is this an ethical position, or for some other reason? Maybe you disagree with this whole framework, but I’m interested in the ways you’d disagree.

One of the issues that comes up with respect to notions of the self and identity is: are my beliefs and feelings constitutive of my subjectivity and of my identity, and are they unique? We are all ideologically informed and narrated. We come into the world, our subjectivities are formed ideologically, we learn to understand the world in particular ways, and it has little to do with some power of uniqueness in the way we perceive things.

Being a Black person or a person of any racial or ethnic group is a consequence, a learned experience. There’s nothing that is genetically or organically determined. If there is uniqueness to the idea of a Black person it’s only because the cultural experience of that person, in other words the experience that person shares with others of their background, is uniquely different from another cultural group. And those differences are ideologically implanted in us over time. We don’t remember learning to speak. We also don’t remember how our subjectivity is formed, in pretty much the same way.

But does that speak to people’s lived experience, the experience of actually being treated as or living as a certain identity?

The only way you can talk about these structures is through lived experience. Language is made of two parts, the language system and speech, and speech is directly the activity of experience, speech is the way that we live with others, but there is a structure that is socially formed. If you pay attention to speech you can pay attention to the things we can speak about. If you pay attention to structure you pay attention to the elements that we use to speak. My proposition is that they are combined.

I was at Bard talking about another one of my works, “Manifestos.” I took political manifestos and translated the letters into musical notation, and the translation was eventually performed by an ensemble. The piece in part is about reading the text while listening to the music. So what happens is that the music is very beautiful, and it creates a certain affect to the text. The manifesto texts are about political issues. And so, because I used a system to produce the music, the way you feel about the music is not related to anything that I intended. It’s simply a consequence of the system.

I got into a debate about that. People said, Well, you made choices. The instruments, or wherever these choices popped up, meant subjective intention was still present. My argument was that the issue that sound produces a physical response and a lot of responses. That’s just its nature. You can’t give legitimacy to something just because those feelings are attached to the experience.

I had no idea what the experience of the music would be like when I was putting it together. But what I did know was that it would have some kind of effect. I’m arguing that the structures themselves create the framework for the formation of meaning. I can show you the impact of structures, or how they affect you, by literally dismantling this cause/effect relationship. If I dismantle that relationship, and the power still remains, to me it shows you how important those structures are in the way we understand things, and the understanding is not exclusively realized in the realm of the lived experience itself.

Your work was at one point criticized for being “too white.” Even today, the Studio Museum website is at pains to tell me that your work “eschews overt discussion of race.” Is a Black artist in America always talking about race, especially when not talking about it? Is this a curse or a gift?

That issue is historical. The questions and problems around that time in the 1970s when I started working are not the same as today, and indeed not the same as the generation before me. Today there are still people who think that artists should be doing political work, but nobody is saying they’re making white art any more. That aspect is dead. So it’s really a historically driven question.

I remember writing a paper about it with respect to 1950s Black artists, the painters, mostly male, who were experiencing the civil rights movement and were at a very dynamic time culturally and historically. There was a reaction or an understanding among these artists that the means of artistic expression do not provide the tools to express the experiences that drove the civil rights movement. Especially in abstract painting, and especially because those painters really loved abstract painting. They realized that the language of experience was not competent in dealing with these social and cultural and political issues.

I was saddled with that question: what is the relationship between what I do and the reality of my day-to-day life? I think it was a crucial critical question, a question ahead of its time, a question that brought in the necessity of the critical issues of representation, at a time when mainstream art was not interested in questions of representation at all. It wasn’t as though I was going to stop making conceptual art— that wasn’t going to happen. But it suggested to me that I had to think through this problem. Later I began to understand because of that question the core of my issues around representation. And then much later, some time in the late ‘80s and the ‘90s, I came to some kind of notion about how to deal with that question of my interests as a conceptual artist and how that overlays with my daily experience as a Black person in this society, which I was able to trace back to my childhood actually.

There’s one little story I’ve told often. I was born in Charleston, South Carolina, and I was walking with my mother and I was about three years old at the time. There were Charleston shacks and dirt roads and farm animals and chickens all over the place. I was looking at a bird and I asked her, if I died would I come back as a bird. I wasn’t thinking that at the time because I was only three, but in some way, this was my reaction to living in a segregated society, living under Jim Crow. Even as a three-year old I understood that that system existed, and so my interest in change, in coming back as a bird, was a kind of metaphor for finding an escape. But I turned it into a metaphysical question. I was making a comment on the strangeness and the arbitrariness of being placed in the world. Some people are placed in the world in privileged situations and other people are placed in the world in underprivileged situations. I was looking at the complete arbitrariness of this and my notion about understanding it through some philosophical notion of change: what if there could be a metamorphosis and my location in the world was changed? That would be some kind of solution.

This makes me think of different possible responses to the question of identity—there’s the structure of race or gender or whatever, and it’s not always so clear how that relates exactly to the experience of being a body in the world. To deal with the mysteriousness of that relation, you can treat it as arbitrary or you can make some kind of intense identification.

An important thing to say is that the arbitrariness of structure establishes how important discourse is. In other words, structures provide us with the means of producing discourse and discourse is where we fight for whatever it is we believe. What my work does is establish the need for discourse and the need for making these various arguments that we might want to make around the politics of race and the politics of gender. There doesn’t have to be a universal Black person in order to talk about the politics of being Black in this society and advocate for various things. All of that happens in the discursive space. All of that happens in speech. So, in speech, we make these discursive arguments. They don’t have to be legitimated by a universal truth.

What’s your sun sign?

Cancer, 23rd June, on the cusp of Gemini.

Do you relate to that?

From what I’ve read, I seem to have many of the characteristics that Cancers are supposed to have. A lot of people interpret my interest in representation as meaning I’m trying to rationally understand the world. Far from it! One of the motivating factors in my early work was the I Ching, which is an ancient Chinese oracle book. I used to ask it all kinds of questions about making important decisions in my life. So I was leaving my decisions to flipping coins. There’s nothing rational about that. Certain astrological narratives seem to be convincing to me, for reasons that are not typical. It’s not that I believe that there is a determining spirit, a master puppeteer, but these ways of understanding the self are part of a continuous discursive narrative. It’s like psychoanalysis. You’re constantly writing narratives about your identity through which you understand who you are. It’s not that you are revealing an underlying truth.