Have you seen the New Aesthetic? Everyone in the Twittersphere was talking about it. Depending on whom you ask, it was a “shareable concept,” (James Bridle) a “theory object,” (Bruce Sterling) and a “weird, hot, movement” (Ian Bogost). Or simply “things James Bridle posts to his Tumblr,” as Bogost quips — and to which we might add, “which got really popular really fast and I wish I knew what it actually was.” Bridle’s Tumblr became a SXSW talk in March 2012. And then a week later, Bruce Sterling wrote a 5,000-word opus on the New Aesthetic for Wired. As if to a younger sibling, praising and cautioning in equal measures, he contextualized the New Aesthetic as not just a Tumblred accumulation but the art movement 21st century creatives had desperately been waiting for. The essay was a flash point, prompting a flood of responses. What better empyrean spark than the convergence of SXSW and, as he describes himself on his Twitter bio, “one of the better known Bruce Sterlings”?

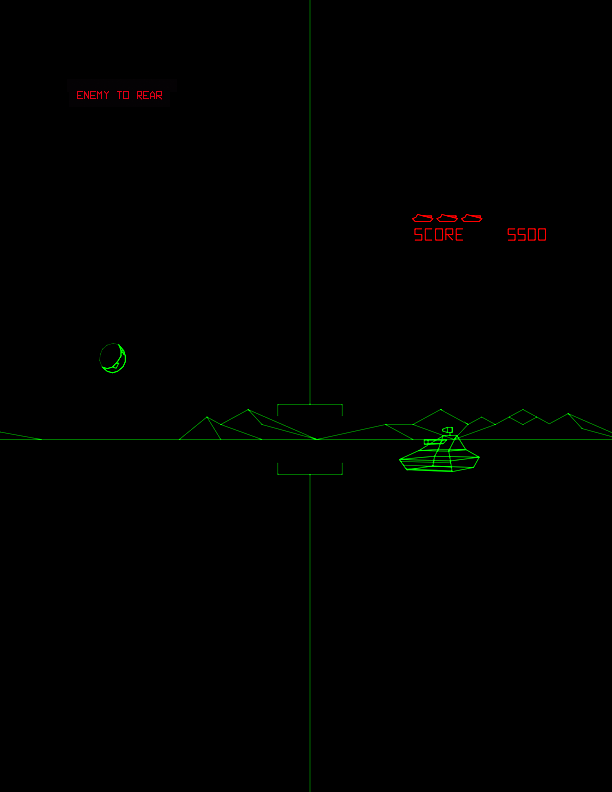

The New Aesthetic Tumblr was around for about a year. Its images, videos, and quotes were summarily collected, attributed, and uploaded with little by way of commentary. Drones, mapping, mirror worlds, machine vision, surveillance infrastructure, conspicuous augmentation, pixelation, fetishizing obsolescence, render ghosts, nostalgia for the glitch, 8-bit reveries, #botiliciousness, souvenir postcards from the robot-readable world, reality media, and the haptic revolution all featured prominently. The New Aesthetic cataloged visual by-products of the increasingly symbiotic relationships between humans, machines, and other possibly sentient objects. That’s all the microblog could do for now; it didn’t speak these other objects’ languages — yet.

Bridle had tapped into an intergenerational zeitgeist, or whatever passes for it in the age of mechanical reblogging. At its base, the New Aesthetic was what he calls “eruptions of the digital into the physical,” an accumulated and curated record of a contemporary reality scanned, monitored, and slightly pixelated around the edges. It was object-oriented — Bridle describes it as a “mood-board for unknown products” — and represented a shifting of the ethnographic gaze from people to mechanical products with inscrutable inner lives, unearthing artifacts and readymades from our present moment. It was about othered things that are cautiously exotic to us, and our dubious relations with them. In a nutshell: robots laughing alone with salad.

Remember the earlier decades of the uncharted Internet, and the pioneering gusto with which certain browser software was named. First came Netscape Navigator, sailing the high seas, followed by Internet Explorer and Safari tentatively traipsing through the World Wide Wilderness. Now it’s time to begin making contact with the natives — with the spambots, mail-order brides, and online apothecarists already appearing unsolicited in our inboxes, introducing themselves in their own languages. It’s time to wonder about their interiority. Are they listening? Are they looking back at us? Do they feel, or even care? Don’t they just want to be loved, too?

The New Aesthetic was undeniably about looking and is itself a thing to be looked at. Yet thus far, with few exceptions, it was a whole lot of men doing the looking, talking, and writing about the New Aesthetic. The Wired essay was followed by several men responding to Sterling, a man, writing about a concept put forward by Bridle, another man. But there are exceptions, including Joanne McNeil of Rhizome.org, and Madeline Ashby, who invoked feminist film theorist Laura Mulvey with a post on the New Aesthetic of the male gaze. Ashby alludes to something seemingly basic but as yet unacknowledged: These new ways of watching are unavoidably gendered technologies of control and domination.

Apparently, it took the preponderance of closed-circuit television cameras for some men to feel the intensity of the gaze that women have almost always been under ... It took Facebook. It took geo-location. That spirit of performativity you have about your citizenship now? That sense that someone’s peering over your shoulder, watching everything you do and say and think and choose? That feeling of being observed? It’s not a new facet of life in the 21st century. It’s what it feels like for a girl.

The New Aesthetic is about being looked at by humans and by machines — by drones, surveillance cameras, people tagging you on Facebook — about being the object of the gaze. It’s about looking through the eyes of a machine and seeing the machine turn its beady LEDs on you. It’s about the dissolution of privacy and reproductive rights, and the monitoring, mapping, and surveillance of the (re)gendered (re)racialised body, and building our own super-pervasive panopticon. The effects of these encroachments upon privacy, though, are not equal. The app Girls Around Me — which meshes geolocation and women’s publicly available Facebook and Foursquare data to variously “avoid ugly girls” or, more menacingly, stalk women — proves the perfect example. As Forbes privacy blogger Kashmir Hill noted in responding to the furor around the app, “ ‘You’re too public with your digital data, ladies,’ may be the new ‘your skirt was too short and you had it coming.’ ”

The attraction of the New Aesthetic for these men may then lie in the chance to briefly experience a traditionally feminized, objectified subjectivity. It allows you to build an identity predicated upon your reflection and image on the screen — on Photobooth, on your phone cameras, in the recent spate of preteen “Do you think I’m pretty?” videos uploaded to YouTube.

But sometimes being looked at becomes almost too much to bear, and you sheepishly put a post-it or some tape over the laptop’s built-in camera. For fear of someone watching you in your sleep, for fear that the machine itself is the voyeur. Are you there, Hal? It’s me, Madonna. Now do you know what it feels like for a girl?

The New Aesthetic reflected a broader turn from commentary (say, blogging) to curation (microblogging). And within microblogging, a turn from the purely textual (say, Twitter) to the visual blend (Instagram, Tumblr, Pinterest). As suggested by writer Shaj Mathew at The Millions, Tumblr has more than a whiff of the commonplace book — the personal notebooks filled with references, phrases, and choice bon mots — favored by writers and orators of centuries past. Visual microblogging more broadly can, in turn, be seen as the spiritual heir of the cut, pasted, and glued zine that brings together text, images and quotes. Rather than simply creating as an artisan might, the microblogger-ascurator brings objects together, contextualizing and co-producing the space at hand — be it in a physical gallery or online — with the help of various network technologies.

Curation is a word long associated with the performance of traditionally feminized labor: A putting together, an assembling, a nurturing, a taking care of things and people. Curing hams and charcuterie and “putting up” produce for the winter. Chicken soup for the common cold; restoratives, remedies, and healing. It’s unpaid labor that structures and enables paid, productive labor. Curation has interesting ecclesiastic connotations too; a curator used to be the religious professional tasked with the care, cure, and guardianship of souls. In art or in publishing, a convenient value markup. And in law, a curator is tellingly “a guardian of a minor, lunatic, or other incompetent, especially with regard to his or her property.”

Curation suggests Rob Kitchin and Martin Dodge’s concept of coded space, as Bridle discussed in a recent, brilliantly named talk “We Fell in Love in a Coded Space.” Unlike “code/space,” which ceases to function without software (think airline check-in desks), a coded space is co-created through use of software — a physical space that is at once also an embedded, networked node. The local bodega, for example, where you can pay for your purchases via credit or debit, or cash when the network is down.

Much of our waking lives are spent in coded spaces. And through curation, our bodies themselves are increasingly coded spaces, co-created with the help of social media, topical and invasive “medi-spa” procedures, lasers and LASIK, surgery, YouTube makeup tutorials, and so on. iProsthetic apps of the nutritional or Nike+ variety count calories burnt or consumed, and are integrated into our increasingly cyborg selves as seamlessly as artificial pacemakers or insulin implants. Virtual makeover technologies now even allow you to upload a photo and “try on” a new you — blunt bangs and scarlet lipstick, perhaps — while avoiding salon floor tears and expensive mistakes. For everything else, there’s Photoshop.

Advances in longevity technologies have cemented mainstream beauty’s synonymity with a quest for eternal youth. As the patriarchal male gaze becomes subsumed by the gaze and vision of machines, it’s worth considering how our own self-curatorial practices might change. Will women swap silicon implants for silicon computer chips that regulate collagen production, for example? Rather than dress with other people in mind, will we begin to dress for machines, for the things that penetratingly scan and photograph us, inside and out? Every day a red-carpet day?

Consider Mulvey’s much quoted statement, “the destruction of pleasure is a radical weapon,” and remember the legendarily ugly bartender of William Gibson’s Neuromancer: “In an age of affordable beauty, there was something heraldic about his lack of it.” Even today, there is a similarly fetishized kind of antiglamour — chipped nails, mussed hair, unkempt eyebrows, visible body hair. Tomorrow, this anti-grooming just might translate to a new subculture of visual resistance: to a lack of conspicuous cyborgification, and a willingness to age disgracefully, wrinkles and all.

What does it then mean for the New Aestheticians to aggregate and curate the future-as-commonplace book? Are New Aestheticians healing a rupture, performing emotional or reproductive labour, guarding and rearing the bots pre-Singularity? Is archiving, in an increasingly ephemeral world, akin to preserving life? (With enough reblogs, we might even approach a kind of transhumanist immortality.)