On July 1, prisoners in the Pelican Bay Security Housing Unit in Northern California began a hunger strike to protest egregious human rights abuses perpetrated against them by the supermax prison and its staff. By the time the strike ended, Critical Resistance documented the participation of 6,600 prisoners across the California prison system, despite media bans and isolation of organizers. The strikers’ demands included an end to the practice of denying food as punishment and an end to the practice of long-term solitary confinement—some prisoners at Pelican Bay have been isolated for four decades and counting. Hunger strikes are a so-called weapon of the weak, a tactic used by those with no bargaining chip except the unwillingness of the oppressor to be held responsible for their deaths, or at least to fill out the paperwork. To quote Hilary Swank’s Alice Paul in the film Iron-Jawed Angels, “Do you really want a stinking corpse on your doorstep? What will the neighbors say?” Used historically by imprisoned U.S. suffragettes, Indian nationalists and more recently by labor unions, the hunger strike demonstrates a sort of radical passivity, a willingness to do harm to one’s own body to protest the harm being done to the collective body.

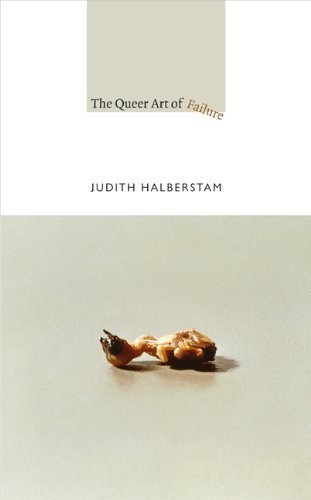

In her new book The Queer Art of Failure, Judith Halberstam, English professor and director of the University of Southern California’s Center for Feminist Research, writes, “In a performance of radical passivity we witness the willingness of the subject to actually come undone, to dramatize unbecoming for the other so that the viewer does not have to witness unbecoming as a function of her own body.” She reads this voluntary fragmentation into Elfriede Jelinek’s The Piano Teacher; the self-injury of main character Erika Kohut becomes the desire to literally cut Austrian fascist nationalism from her being. In Jamaica Kincaid’s Autobiography of My Mother; abortion and disavowal of biological family become a kind of evacuation of the occupied subject—a self-destruction that also brings down “the edifice of colonial rule.” Halberstam writes about female masochism in literature, collage, and performance art—for example the artist’s refusal to “resist in the terms mandated by the structure that interpellates her” in Yoko Ono’s canonical Cut Piece. If the capacity to act cannot be divorced from the definition of the dominant subject, if freedom can only be imagined in terms of the “freedom to become a master,” then perhaps, Halberstam argues, the only possible act of agency is the refusal to act at all.

The Queer Art of Failure vacillates in its chosen subjects of critical analysis from the aforementioned masochistic female performance art to white-boy amnesia in comedy to hidden anticapitalist radicalism in Pixar films to oft-ignored histories of gay fascism. Drawing on a broad archive of negativity, the book seeks to queer the idea of failure while also functioning as a (loving) critique of recent antisocial queer scholarship in the work of Leo Bersani, Lee Edelman, and others (including a less loving critique of Slavoj Žižek). The Queer Art of Failure sometimes embarks on a positivist project in which “failure” stands in for alternate paths to triumph and sometimes calls for failure to be taken on its own terms, rather than as a “stopping point on the way to success.” Declaring her own project “a kind of ‘SpongeBob SquarePants Guide to Life,’ ” Halberstam revels in her “silly archive,” attempts to read meaning into texts disdained by some in the cultural studies world like cartoons, stoner cinema, and romantic comedies, as well as “high culture” visual and performance art. Proposing a “low theory” antihierarchical mode of inquiry which operates in a state of intentional confusion or contradiction, Halberstam asks the reader to “consider the utility of getting lost.”

Many of the readings out of Halberstam’s “silly archive” are overly hopeful—the monster-proletarians in Monsters Inc. may find an affinity with the children they are paid to scare, but the transition from scream factory to laugh factory is a liberal vision at best, with alternative energy pacifying the desire for alternative futures. Halberstam asserts that the stupidity of Jesse and Chester in Dude, Where’s My Car? represents a space of unknowing that allows for queerness—Fabio-goaded make-out sessions and transsexual strippers—but doesn’t account for the domestic mediating presence of “the twins,” or the extended gross-out scene upon the revelation that hot stripper Tania is a “gender-challenged male,” in the character’s own words. Halberstam advocates a praxis of negativity, argues for the utility of forgetting, and valorizes self-destruction of the colonized subject and a feminine masochistic fantasy which transfers punishments “onto the body of the oppressor,” while failing to acknowledge that there is actual corporeal suffering at stake. As E. Patrick Johnson asks, “What is the utility of queer theory on the front lines, in the trenches, on the street, or anyplace where the racialized and sexualized body is beaten, starved, fired, cursed—indeed, when the body is the site of trauma?” Where is the radical possibility in unbecoming when you are already being unmade?

Halberstam goes so far as to declare that “cutting is a feminist aesthetic proper to the project of female unbecoming.” Cutting here refers to a set of dissections that includes self-harm but also collage (an art form based on not only cutting but the act of assemblage to create a new whole). Operating from a psychoanalytic understanding and responding to the Freudian assertion of femininity as failed masculinity, the exploration of radical passivity sets up an oddly essentialist gender dichotomy that omits an analysis of male femininity while lauding female disappearance. The dismissal of male masochism as “a kind of heroic antiheroism” while setting up cutting as a proper feminine aesthetic has almost conservative implications. Following a certain line of popular psychology, women and girls are considered statistically more likely to engage in self-harm, while men are more likely to lash out towards an outside target; an essentialist distinction of supposedly active versus passive violence. But there is a statistically much higher rate of male self-injury in incarcerated populations, a correlation that evokes, again, the idea of “weapons of the weak” and a sort of willfully necropolitical resistance to social death rather than Halberstam’s heroic anti-heroism—operating itself from a (racialized) masculine place of powerlessness within the structure. Rather than dismissing masculine “martyrdom,” one can draw a distinction between performatively “giving up” social power and already operating from a place of powerlessness. The proper aesthetic of (feminine) self-destruction, when performed offstage, can also engage a darker failure, such as the emotional splintering under the weight of oppression—as Audre Lorde attests in the poem Who Said It Was Simple: “sometimes the branches shatter before they bear.”

Returning finally to the California hunger strike: At the end of three weeks, the prisoners at Pelican Bay began eating again. They received a bare minimum of concessions from the state, including the right to wear caps in cold weather. Many had lost significant and dangerous amounts of weight and suffered serious medical complications, while facing constant harassment and repercussions from prison guards. The strikers willingly, even willfully, approached actual death in the face of constant social death, in a U.S. judicial system that locks up and forgets those deemed undesirable. Though they ultimately chose to “live to fight for justice another day,” in the words of mediator Dorsey Nunn, the strike importantly proved the possibility of organizing across prisons and even through solitary confinement, and drew public attention to the injustices of the U.S. prison system and the use of torture in supermax prisons. Out of the radical passivity of the hunger strike at Pelican Bay, out of the invisibility into which these incarcerated men disappear, emerges a hazy outline of the prisoners as agent. “Unbecoming” functions as a tactic of resistance more than a total annihilation—the desire to dismantle the prison and the terms of imprisonment without dismantling the self. Choosing to “live to fight” rather than die to prove a point, the imprisoned bodies at Pelican Bay and other California prisons constitute themselves as the collective subject “strikers” rather than the massive body-object “prisoners.” They won’t accept the terms of freedom as offered, but they also refuse to die quietly and alone, as their collective unbecoming simultaneously necessitates and brings about a becoming collective.