The appeal of a murder is knowing that it has happened to someone else

A woman presses her ear to a door. On the other side, her lover and a strange man are talking. She has reason to suspect they’ve committed a murder, and realizes that it’s foolish to eavesdrop. What if she hears something conclusive, proof that her lover has killed someone? She’ll become a witness, responsible for what she knows. She’ll have to hide her knowledge from her lover. If he guesses that she knows, she may become a target. Yet she continues to listen, as any of us would. “The temptation,” she says, “is irresistible, even if we realize that it will do us no good. Especially when the process of knowing has already begun.”

The woman is María Dolz, the narrator of Javier Marías’s sprawling and spectacular new novel, The Infatuations. Marías is wildly successful in Spain, often called Spain’s greatest living writer, and critically venerated throughout Europe, but he remains relatively unknown to U.S. readers. Published in Spain in 2011, The Infatuations is a hefty and patience-requiring book that also seems capable of flying off the shelves. Marías has long been described as a cerebral writer, meaning that his prose showcases his intelligence, but also meaning that it satisfies a desire for sophistication thought to belong particularly to brainy readers. The opposite of cerebral, in this context, might be accessible, as we tend to call writing that aims for simplicity, which is a form of inclusiveness. This book, it turns out, is accessible. It hooks into a kind of desire that is all but ubiquitous. All men by nature desire to know, says Aristotle. To enjoy this book, and to get into trouble because of this book, all you have to be is curious.

This is in no small part because The Infatuations is a murder mystery. Who can resist a good one? We learn on the first page that a man has been stabbed to death. María Dolz happens to know this man. For years, she’s seen him and his wife at the café where they habitually breakfast. She admires their elegance and camaraderie and calls them, privately, the Perfect Couple. When she finds out that the man, Miguel Desvern, has been murdered, she approaches the woman to offer her condolences. Soon she’s invited to the couple’s home, where she meets the lush-lipped, enigmatic Javier Díaz-Varela, who was Desvern’s best friend. She becomes his lover, and their entanglement gradually sheds new light on the murder. The final plot twist begins by seeming so ludicrous as to be insulting and ends by being chillingly, thrillingly persuasive.

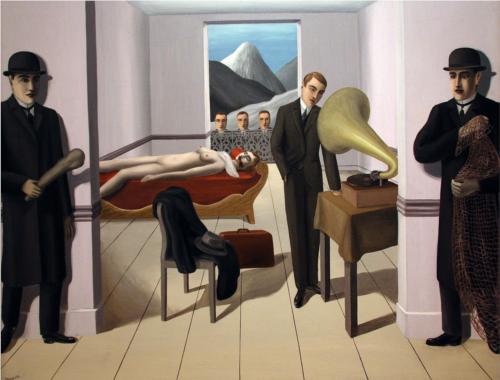

The image with which The Infatuations opens—a newspaper photo of Desvern “stabbed several times, with his shirt half off, and about to become a dead man”—is a glinting, unmistakable hook. Satisfying our curiosity about Desvern’s death—finding out how it was that his murderer attacked, how many times he was stabbed and in which parts of his body, how long he took to die—is a thoroughly pleasurable sensation. Of course, that’s the thing about murder mysteries: Unlike murders, they’re pleasurable, and they’re pleasurable because they’re safe. They provoke and then satisfy our desire to come face to face with the worst that could happen. At the same time, they reassure us that the only possible place for such an encounter is in a work of fiction. Close the book, and the danger goes away.

As we’re racing to find out the gory details of the stabbing, we are, of course, in the company of María Dolz, our narrator. It’s she who’s doing the investigating, Googling “Desvern murder” and scanning online newspapers. Dolz is in her late 30s and works at a publishing house in Madrid. She’s an acerbic, even supercilious narrator, prone to severe judgments of others, particularly of their sartorial choices. Good taste is the thing in the world that most impresses her. Whenever she thinks of the photo of the dying Desvern, “with his wounds on display …lying sprawled in the middle of the street in a pool of blood,” she’s disgusted and launches into a rant against people who enjoy consuming images of violence. Dolz takes a scalpel to these “disturbed individuals” fascinated by the tragedies of others and peels back their worldliness to expose their fear. She imagines their self-comforting thoughts: “The person I can see before me isn’t me, it’s someone else. It’s not me because I can see his face and it’s not mine. I can read his name in the papers and it’s not mine either, it’s not the same, not my name.” It’s hard to miss that the fear being exposed is our own.

Being dissected doesn’t feel safe, especially when the blade exposes something we didn’t know about ourselves. Late in the novel, we find Dolz listening to a story of someone’s horrendous misfortune. Her lover, Díaz-Varela, is telling the story, and Dolz, good taste gone to hell, is fascinated by its gruesomeness. But she doesn’t believe the story. Neither do we. For one thing, the suffering of the stricken person is too monstrous to be believed. For another, Díaz-Varela simply isn’t to be trusted. Realizing that Dolz doesn’t believe the story, Díaz-Varela makes no effort to prove its factuality. Instead, he tells her condescendingly, “Don’t worry, that particular [awful tragedy] is, fortunately, very infrequent and very rare. Nothing like that will happen to you… [It] would be too much of a coincidence.” We understand that he’s speaking not to Dolz but to us. What’s astonishing is the effect his words have. Condescending as his tone is, and baseless as his prognostication is (he can’t know, after all, what will or won’t happen to us), we are helplessly relieved by his words. Thank goodness, says the gut, in the split second before consciousness steps in. Thank goodness I don’t have to worry about it happening to me. Instantly, the story of the tragedy seems more plausible. It turns out that our former disbelief didn’t have much to do with a concern for truth. It was merely selfish, self-protective. For a frightening instant, we glimpse the current of denial on which we float toward death.

If this book were only a murder mystery with a hidden agenda—namely, to expose the messy nature of our relationship to the suffering of others—its project would be interesting enough. In fact, the novel’s scope is more diffuse and surprising than that. One of Marías’s hallmarks is a provocative plot, but another is the way in which plot turns out to be only a hanger for the great, luxuriant garment of his digressions. In this book, the action, crucial as it is, accounts for perhaps 10 percent of the page count. Scenes are rare. Interactions between characters, as well as movements of characters through space, exist to provide triggers—occasions for one character or another to launch into a meditation on human experience, or a response to a work of literature (Macbeth, The Three Musketeers), or a moral thought experiment.

While they’re discoursing, all the characters sound the same. It’s hard not to assume that the voice they share—sharp, erudite, capable of thinking in page-long sentences—is that of Marías himself. The tension of the narrative flags when plot falls away, and as we turn the pages, part of us is waiting for Marías to circle back to the action. Another part, though, forgets the action and becomes interested in the digression itself. We begin to wonder about our own thoughts on the topic Marías is exhausting. We want to know. This wanting to know isn’t curiosity, exactly, but a slower-burning interest; we can feed it as fuel to our patience. The real genius of this book is that it will make you shut the book, lean back in your chair, and consider an abstract and formidable question.

For example: the nature of time. Early in the book, Dolz attempts to console Desvern’s grieving widow, Luisa Alday, by reminding her that his suffering was very brief and is now over. Alday refuses to be comforted. “Yes, that’s what most people believe,” she says. “That what has happened should hurt us less than what is happening, or that things are somehow more bearable when they’re over… But that’s like believing that it’s less serious for someone to be dead than dying, which doesn’t really make much sense, does it? The most painful and irremediable thing is that the person has died; and the fact that the death is over and done with doesn’t mean that the person didn’t experience it.”

The metaphysical land mine here is the reminder that the past, like the present, is real. Think about this, and it will explode your notions of the passage of time. Day to day, we take for granted that we move forward. We’re preoccupied by the future, since we’re moving toward it, and we feel, or are told we should feel, the past drop away and recede behind us. But the past is still real, the way someone who’s far away is still real. It’s feasible that our sense of moving forward through time is only an illusion, attributable to the decay of our memories. If we cease to be haunted by our dead, it’s not because they are not real but because we have forgotten them.

Later in the book, Díaz-Varela contests what seems self-evident about our relationship to past events: that we are capable of regretting them. “What seems like a tragic anomaly today will be perceived as an inevitable and even desirable normality, given that it will have happened,” he says. “The force of events is so overwhelming that we all end up more or less accepting our story.” Surely we can all point to something in our past and say: This I have not accepted; this I regret. And yet it’s also true that everything that happens to us becomes part of our sense of ourselves.

Díaz-Varela invents an example, a man whose father was cruelly murdered in the Spanish Civil War. This imaginary man “is a victim of Spanish violence, a tragic orphan; that fact shapes and defines and determines him.” Had he not lost his father to violence, “he would be a different person, and he has no idea who that person would be. He can neither see nor imagine himself, he doesn’t know how he would have turned out, and how he would have got on with that living father, if he would have hated or loved him or felt quite indifferent, and, above all, he cannot imagine himself without that background of grief and rancor that has always accompanied him.” In a sense, we can’t wish that the past hadn’t happened, because if it hadn’t, a stranger would be standing in our shoes.

Díaz-Varela even claims we are incapable, after enough time has gone by, of missing our dead. “We can miss [them] safe in the knowledge that our proclaimed desires will never be granted,” he says, “and that there is no possible return, that [they] can no longer intervene in our existence.” Alday might counter that if missing a dead person feels safe, we are not actually missing them, but failing to confront the reality of their having died. Though her perceptions and Díaz-Varela’s seem opposed, they aren’t really incompatible. Each of them is arguing that the present is an overwhelming, all-consuming state. It’s simply that each of them is experiencing a different present. Alday is freshly bereaved, and it’s the nature of terrible grief that it feels as if it will last forever. Díaz-Varela’s cold peak of logic can only be reached in the absence of urgent emotion.

The title of this book suggests that urgent emotion is at its center—that the novel has something to teach us about what it’s like to be madly in love. In fact, the titular infatuations (“fallings-in-love” would be closer to the Spanish noun enamoramientos, but would make for an awkward title) are difficult to care about. Dolz is in love with Díaz-Varela; Díaz-Varela is in love with Alday. They exhibit warped behavior, as people in love do, but it’s hard to take their risk of pain seriously. Maybe it’s because infatuation is a physical crisis, and Marías does not trouble to locate the reader in an ardent body. Maybe it’s because he rarely allows his characters to experience conflict in scene.

Attempting to diagnose the problem, of course, implies that there is a problem—that the chief role of characters in fiction is to make us take their pain seriously. Marías wouldn’t agree. At one point in this book, Díaz-Varela claims that what actually happens in a novel “is the least of it … What matters are the possibilities and ideas.” Ideas are what Marías loves, what he works to make us take seriously. In a sense, his characters are themselves only digressions—subordinate to the idea at hand, a way of elaborating upon it.

Essayist Phillip Lopate has spoken eloquently of the digression as a formal prose technique. “The chief role of the digression,” he says (speaking of essays, not of fiction), “is to amass all the dimensions of understanding that the [writer] can accumulate by bringing in as many contexts as a problem or insight can sustain without overburdening it.” Marías’s characters serve exactly the same role. Perhaps The Infatuations is a novel that’s on the verge of being a personal essay. If there’s something unsatisfactory about the book, that’s it.

But forget the characters’ love affairs. The point of reading this book is to have a love affair with it, with the rambling, hubristic, magisterial project of it. If we think of prose itself as the surface of a book and of the ideas conveyed as its interior, then this book, like most infatuating things, possesses great surface beauty. Marías’s prose is graceful, rhythmic, and exact. His longtime translator, Margaret Jull Costa, does smart, elegant justice to his sentences. A description by Dolz of Díaz-Varela in mid-peroration perfectly describes how you’ll feel about Marías if this book succeeds in infatuating you. “While he continued to expatiate,” she says, “I couldn’t take my eyes off of him.”