Artists and critics should combat stylistic prudishness, overcome guilt and shame, and embrace discourses promiscuously

The characterization of Warhol’s noncommercial work here as the product of some lower-class fey hobby served to position it as a kind of “fag” art, and Warhol himself as swishy queen whose artistic pretensions just couldn’t be taken seriously. This is an explicitly “homosexualized” construction of Warhol which dominates in the 1950s, both in relation to his work and his social persona, was instrumental in making Warhol an unsuitable candidate for the artist-subject position well into the early 1960s. Warhol was a window dresser in the mid-fifties and put together displays for Bonwit Teller and Tiffany’s ... Even though the Pop artist James Rosenquist, as well as Johns and Rauschenberg themselves, had also worked dressing windows, it was something that most artists tried to distance themselves from upon becoming successful as artists. Warhol, on the other hand, was famous for his commercial work and didn’t appear to be doing it just to survive. Thus Warhol appeared to be identified with window decorating in a way that other artists did not, and moreover, with a profession which was readily identifiable as a sissy occupation.

—Gavin Butt, Between You and Me, Queer Disclosures in the New York Art World, 1948–1963

Who's crushing on whom? I like to think of artists’ usage of materials and themes in terms of flings, relationships, crushes and marriages. What do artists make, with love fresh in the air, in a new space when long-term relationships have fallen apart or are nonexistent, with no stakes beyond the present? Young artists are making due with minuscule studios, without past familiar art-education facilities, wandering, trying to find all the necessary supplies, devoid of disposable income. Those first few casual friends with benefits in a new city, in a small cramped apartment that lends itself to only half your sexual imagination.

Some artists have a type: big-breasted blondes, stocky Italian-Americans, neurotic catty introverts who just want to stay in all the time, older professorial types to help combat daddy issues. Other artists don’t want that. They want fun fun fun and take it as it comes, throwing themselves into whatever turns them on in the moment.

Art criticism, like an upset parent, often passes moral judgment on this promiscuity, scolding, judging indiscretions. There are attempts at keeping art pure, delineating what is what, and who is who, and where the boundaries are. Or in the attempt to redefine the boundaries, there is a tendency to violently sabotage what came before if it doesn’t smoothly fit into the new regime.

But it’s crucial to encourage brief brushes, longed-for encounters, and magical moments that pass into the night to be brokenly remembered in the hungover daze of the next morning. Flings, one night stands, and vacation hook-ups are just as ripe. For artists who tie the knot—explosive divorces, whimpered muttering and weepy withdrawals, quiet bitter unspoken tension.

Likewise, art writing must attempt to draw new connections, weaving in unpublished, hushed talk that always gets spoken but generally not on the record. The documentation of the piece, the Facebook posts, tweets, and vines that surround such work, the gossip about the work in the bathrooms of the gallery and outside during the smoke breaks and back in the patios and bars after the opening, the press releases both in unchecked email and listserv format, and the 10,000 art-opening invites that networked artists receive each day on social media, the write-up of the work, the studio visits, the sketching out of the ideas, the conversations that influence and sustain the practices—all these are rich and evocative and can provide tremendous energy and meaning to a work and extend its life out beyond.

Artists are keen to this, that every stage of the work’s life is up for play and that there is no such thing as a fixed neutral, ultimately true iteration of the work. In line with refusing criticism’s moralistic impulses, I want to outline the pleasures that manifest themselves through the sites of production—the constant onrush and stimulation of daily life, the influence of the day jobs artists carry on both the making and the documentation and presentation, the opening up of the game, and the heroic attempts to bypass shame.

I think of people getting made up and fabulous, ready for a night on the town, scoffing at such prudes who advise a more “natural” and “authentic” way of representing themselves—their elaborate play and fluidity as they cycle from situation to situation, conversation to conversation, adjusting on the fly and letting themselves take in the experience while also manipulating it.

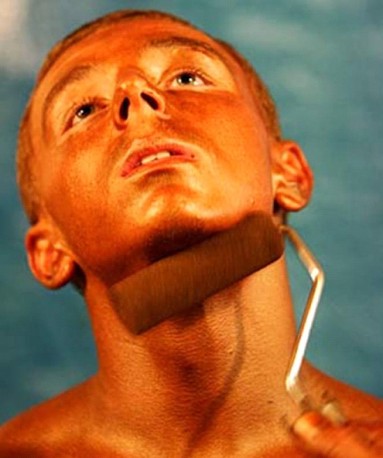

Just as readily, in a flush moment at the gym, the activity of bodybuilders springs to mind. They are in a constant state of sexual satisfaction as they tear down their muscles, letting the body tremble and quiver and blood come rushing in, the everlasting pump. Bodybuilding has been transformed from its European roots as an attempt to mirror with the body the Greco-Roman sculptures being excavated in the 19th century and installed in the new museums. Early bodybuilders would sneak through the museum and tape-measure the sculptures head to toe, formulating the correct proportions according to wrist size.

Contemporary bodybuilders are beyond such concerns and allegiances to an imagined history. Supplements, drugs, new machines, and other practices have allowed for bodybuilders to obliterate the past standards and achieve a new, more abstract result. They adjust their schedules in opposition to the socially approved distribution of hours and home in and work one specific aspect of themselves to exhaustion. After such elongated erotic performances, they step out under the bright lights, covered in extreme bronzer, to bring out the muscles that look incredibly cartoonish under any other circumstances but the bright lights of onstage competition.

It is with bodybuilders and their ingestion, consumption, refinement, and enhancement of past strategies and the conscious toying with their presentation and documentation in mind that I consider Michael Sanchez’s argument about the impact of the iPhone on art exhibition. In “2011,” an essay in the Summer 2013 issue of Artforum, he discusses the way such devices and image-aggregator sites like Contemporary Art Daily interact with and inform contemporary artworks. Art is rapidly referencing itself, speeding up the previous print- and exhibition-bound seasonal schedule that put forth the studio evidence of trends only every few months. Now, as Sanchez notes, things get posted when finished and shared instantaneously, and as a result, similar artists working with similar materials or similar ideas can no longer be tied to a eureka moment: A-ha! This must be the zeitgeist if these unconnected figures are all doing it once!

Instead, the proliferation of work on the Internet makes it easily digestible and citable. New practices, in Sanchez’s view, instantly devour themselves. I think it is necessary to flip the destructive, gluttonous connotations of devouring and focus on the more positive connotations of the word, that emphasis on avid enjoyment. What is so appealing about such fast distribution is how the institutionalized approaches that once suffocated, purified, cleansed, and straightened up the circulation of art are now infused with the chitchat and gossip of social life, and the work is tossed out onto the dance floor, knocked down from the balcony overlooking the frenzy. It isn’t, “Oh my, check out that stoic hottie—that removed, super-distant installation at Kunsthalle Wien. Man, I wish I could ask him if he wants to dance, but I’m so nervous, and he’s so up there.” Instead, in both the quick-feed call and response and riffing and sharing, it is shooting a flirty raise of the eyebrow, adjusting your posture accordingly, and striking up a conversation and making the advance. The stilting and privileging, the attempts to put one group up above another, are falling apart. Everybody is fucking everybody.

In thinking of such juicy tidbits and romantic affairs, I think of Warhol, who was always up to hear the dirt on the previous day and chat at great lengths about the things around him. Through Warhol, the shame and sexual guilt of commercial work is flattened and laid to rest. Also through him, the everyday, the sensational, the banal “low talk,” such as gossip and monosyllabic utterances and the carefully crafted considerations of the artist’s body and appearance, can be claimed and raised in stature.

A sexual response, arousal, and enrapture in the materials and rituals can form an artist’s work and structure what it draws from. Artists are giving themselves over and opening themselves up to those things that stick out, that linger, that give pause, that provide both evident visible pleasure and inwardly-kept satisfaction, that they can’t get out of their head, that horrify them but they come back to, that humiliate and punish, that build and nurture, that annoy and tease, that they find themselves needing more and more of. These are precisely what is so invigorating about today’s art.

Am I shocked that multiple people are getting excited about and engaging Axe, its body sprays, shampoos and deodorant? No, Axe is insane, its projections so ridiculous, the smells so pungent and easily dispersible, catching a trace of it when you aren’t even ready, getting smacked by those omnipresent fantastical video clips running in a constant stream online. Axe is so blunt and in your face that an artist was eventually going to have to go up and flirt a little bit with it.

Artists don’t have to sign a mortgage with the things they work with, and it is perfectly normal to kind of hate the people you’re attracted to. Gosh, she’s so wonderful and smart and well-read and funny, but she’s a horrible drunk and she farts in her sleep. Or: he’s such a belittling and abusive asshole, but I kind of need that deprecation in my life right now, it is hot, I can’t help myself, I know it isn’t “normal” but it is working so well right now. Please keep the stories coming, and the encounters memorable.

There should be no guilt in the little tricks and joys that the photographer takes as she shoots yet another wedding or another shampoo commercial. No guilt for the studio assistant as he minutely changes the slightest tone of the shadow in Photoshop on a hurried, last-minute assignment. No shame for the sculptor achieving bliss as she gazes out at the perfection that is the Dyson Hot + Cool fan or for the painter as the hairs on his neck stand on end as he takes in a perfectly luminous, kinky kids’ plush toy. No guilt for the performance collective as they assimilate the back-and-forth exchanges between pro wrestlers and their audience.

The little welds on the underneath of the chair, the otherworldly quality of the Ped Egg suspended in some floating advertisement, the catalogs for car shows, all those marvelous oddities that are liberated from art’s guilt complex, strutting flamboyantly through such longed for and un-actualized concerns.

There’s something to be said for the repetitious, paying-the-bill qualities of getting the thing right, getting it to look exactly how it needs to look, and making sure that it looks damn good and not dejected. That seems to be an undercurrent of the sculpture that wants to cleanse you, as it builds on the minimalist introduction of plastics, resins, metal, and other industrial materials in their stark punctuality—slickness and play with space along with the straight-out fling with branded body products, as configured by a generation of artists who aren’t guilted into previous high-low, worthy-unworthy binaries, using the commercial skills and craft that they acquire in their day jobs.

Artists working today don’t own this fact enough. They’re still too meek about it. America always had a Warhol problem when he was alive, in that his flamboyance was too much for some folks who preferred their artists, like Johns and Rauschenberg, to deny their commercial activities and keep themselves pure from such daily occurrences, taking up residency in certifying institutions that still believed art was above everything else. There’s still this leftover anti-market stigma that sneers at both those who sell and those pay the bills in less pure and wholesome fashion. As if the only way to be a valid artist is go to pro, shuffling through the residency cycle, taking adjunct positions with only one semester of your life planned at any moment, hoping for some fantasy placement so you can be above the daily fray. The shame of selling, and the shame of admitting that you might find certain qualities of your day capable of being relevant to the things that art struggles with is still taboo, amazingly.

Such practices apply not only to the production of work but also to documentation and circulation. Artists are getting more honest about what turns them on across the board, and this includes browsing, looking, staging representations, and resharing—owning the way you like to browse, the way you like images to look when you see them, hiding the muffintop you’ve got creeping over the side of your pants by wearing high-rise jeans, putting on a little cover-up, turning your good side to the camera, standing next to someone smaller than you in every picture, making the lights a little bluer in every photo, obscuring the information inscribed on the situation, making pointed removals, and any other playful actions.

Sticking up one’s nose at practices previously rejected as serious art—fashion photography, car painting, furniture and website design, among other commercial trades—seems further and further removed with each new MFA class, as young artists let more in and open themselves to wider possibilities.

Although I’m not an artist, there’s a personal story that plays in my head when I view a lot of work that touches on these arousals. I’m reminded of an experience I had as a tween at a summer camp where my mom worked as a nurse. It was the first week, everyone still sunfree, completely new to each other, feeling out the situation, the potential for incredibly awkward encounters rampant. One day we all waited in line to get in the showers with our towels and Adidas- or Nike-brand flip-flops, and talk inevitably turned to dicks, in all of their varieties.

What amused me about this not-so-uncommon encounter was the eventual turn in the conversation to shampoo. Everyone at the time had the new fish-like bottles of L’Oréal for Kids, with its emphasis on the no-tears, no-pain qualities of its chemical makeup and constant allusions to the earthy and bodily sexual qualities of fruit. Everyone proceeded to measure their dicks against said bottles, terming the new discovery a L’Oreal boner, each one of us with a different bottle.

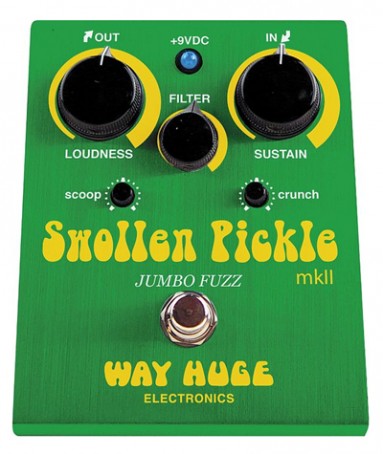

The way artists actually talk about spaces, casually at lunches and on the way to things, has always been in my experience closer to the language used to describe music: Things are harsh, ethereal, fuzzy, stark, amplified, severe, ringing. Out of context, if you missed the first few words, you might think they were discussing guitar pedals or a set of sounds on a drum machine.

Music hasn’t traditionally been as reliant on proximity to or participation in certifying institutions in the way visual art has. A producer from the middle of nowhere can throw up a track on Soundcloud after being inspired by some other, more-well-connected artist and quickly enter into the dialogue.

Visual art should be jealous of this fluid accessibility, these leveling maneuvers. Kids far from the art capitals can give themselves a playful legibility that is constantly up to be teased out and undermined. It isn’t realistic for young would-be gallerists to acquire a space like the De Vleeshal, but with a little paint and lighting know-how, they can transform their crappy garage, bombed-out basement, or parent’s attic into their own gallery space that is gonna look great all done up and out there.

Why privilege one level of the art speech act over another? Sure, some work might be underwhelming in person, in comparison to the space that looked so big onscreen, but the work is just as true in the studio as it is in the gallery, as it is on a website, as it is in a book, as it is on a phone, as it is during pedicure and manicure parties, as it is when barely remembered and floating as an example to be used in a conversation that never quite makes it out, as it is in a minuscule press clipping that some art historian will dig up a hundred years from now while writing a dissertation. Each new iteration allows for an unlimited amount of possibilities for artists to use, to extend and pause and speed up and burrow in and rewind and cut and paste and reverse and queer and undo and build upon, and as such, none should be shut down.

I think of this new work as coming to grips with its sexual inclinations, its desires, its wants and needs, its fetishes, how it wants it, and when, and from whom, and with whom, and where, and for how long. I’m curious to watch it as it further announces its own notions of identity and desire, comes to terms with the pictorial and critical vocabularies it draws from and turns them inside-out again and again, fighting prudishness every step of the way.

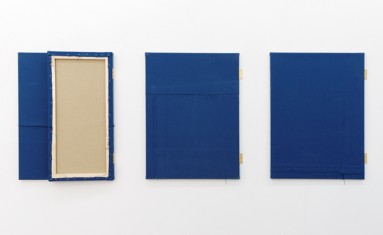

In “2011” Michael Sanchez also discusses abstract paintings that he says gain specific qualities due to specific tones and colors in their relation to the screen. These medium-specific concerns might seem a nostalgic longing for an imaginary time when art was clearly concerned with the “right” issues before the great beheading and subjugation of opticality, but such work is just as sexually courageous as the meme art and neosurrealism discussed above in its refusal to acknowledge pronouncements on its death as a viable practice, such painting owns its own shamed sexual stature. When critics deride such work, they frequently employ the language long used to attack masturbation. It is overly selfish and inward looking, playing in a cul-de-sac with clearly definable ends and goals and a limited focus (the most boring rise and climax that doesn’t let anyone else in). And its emphasis on opticality is especially seen as masturbatory, as this is tied to the accusation that such work refuses to self-critique and police its status as a commodity object, that sensory experience that isn’t as rigorous, respectable, and healthy in a relationship as the experiences tied to the other senses. It is too easy and too limited, and doesn’t interact with anything but itself, jerking off and acquiring hairy palms.

It is necessary to rescue masturbation and masturbatory art from stigmatization, as these critiques and others like them attempt to shut off the possibilities such work can have, both in past incarnations and new practices.

Masturbation is often said to stem from psychological weakness and moral decrepitude, or to be caused by a lack of “healthy” relations with others. It’s depicted as always a rote, banal and repetitious event. This is bullshit. Masturbation can provide its own intensely empowering and enlightening and inspiring experiences. The joys of masturbating in the shower, masturbating when you have all the time in the world, when you’re rushed, when you’re all alone in the apartment, when there’s someone in the next room, when you’re imagining something in your head, when you’re looking at an image, when you aid the process with other fluids and devices, imagined assemblages.

Masturbation isn’t interesting only to the person who is masturbating. I think of friends masturbating to Skype screens for their partners across the country. The play and teasing, that exciting back and forth, the way your legs tighten, how the sweat glistens on your stomach, how you bite your lip, the slight noises you make, the arching of your back, the way the pace quickens and slows, the way you toss and turn and throw the pillows around. But for the masturbatory artist, the audience need not be literal but can be implied.

A lot of masturbation verges on more conventional sexual exchanges, just as there is sex that verges on masturbation. Events can fluidly circulate back and forth between the two, and open up new potentials. An artist should enjoy both, blend them, and engage however the hell they want, just as artists must have flings, one night stands, quiet flirtations, long-distance relationships, marriages, and multiple partners. Far from announcing the death of a medium or signifying only mannerist pranks, as often is claimed about the stylistic shifts of protean artists like Warhol, Picabia, and Richter, the back and forth indicates a ravenous, all encompassing appetite that can’t be satisfied, that longs for desires still yet to be fulfilled.

I hope artists stay horny.