Early Americans brought a "can do" attitude to the problem of food storage

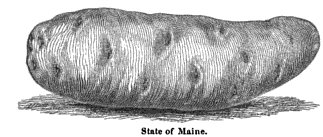

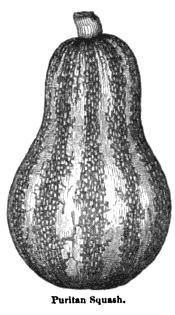

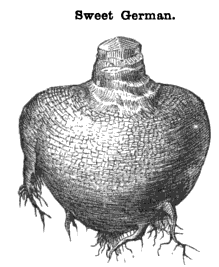

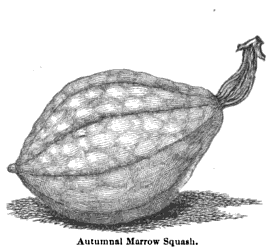

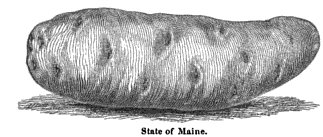

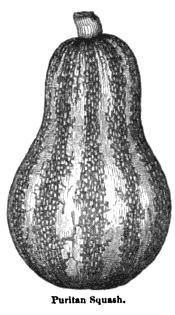

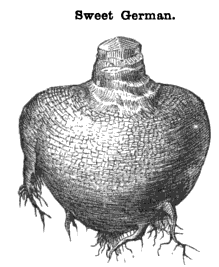

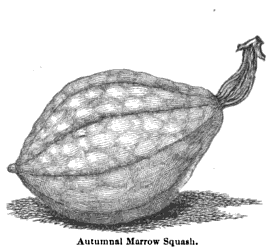

Illustrations from The Field and Garden Vegetables of America (1874)

Once I've settled in a town, I make a point of visiting the local farmer's market. Only there may I get a sense of what's in season, as well as a sense of place -- no mean feat in a country littered with strip malls housing Trader Joe's, where kale and apples spring eternal.

"The farmer's daughter hath soft brown hair / (Butter and eggs and a pound of cheese) / And I met with a ballad, I can't say where, / That wholly consisted of lines like these." --Charles Stuart Calverly

Every Wednesday and Friday there's a farmer's market in my new burg. It's small, featuring usually no more than two stands in the central plaza. One is staffed by an Amish family, the other by a middle-aged woman and her teen son. The folks at both are disarmingly friendly. Eager for conversation, I chat with them as I palm their beets and thump their melons. I buy and talk, talk and buy. Of course, I end up with way more produce than I can eat. A typical trip sees me trudging home with some five pounds of tomatoes, two monstrous heads of romaine, a dozen beets, three dozen eggs, and a jar of honey. I have neither children, livestock, nor compost pile, mind you -- only a partner tractable enough to eat what he's served.

"Life -- a spiritual pickle preserving the body from decay." --Ambrose Bierce

"We must be firm and patient in punishing, no matter how much we love the one who has done wrong, nor how hungry she is. It does no good to whip a person with one hand and offer her a pickled beet with the other. This confuses her mind, and she may grow up not knowing right from wrong." --From the Thought Book of Rebecca Rowena Randall (1906)

Yet even the mildest man can eat just so many beets. Unless I wanted to open a third stall at the market, I had to think of more creative ways to manage my bounty. (Curtailing my shopping was out of the question; it's too much fun.) Pickling came to mind. I had cultured yogurt, fermented apple cider vinegar, and even bottled my own wine, but I had yet to pickle or preserve. Such kitchen arts had always seemed unduly complicated -- all paraffin, pressure cookers, and mason jars. A landslide of cukes and bell peppers that had me slipping and stumbling around my kitchen steeled my resolve. I sat down with the U.S. Department of Agriculture's

Complete Guide to Home Canning and Preserving. Unfazed by warnings therein about botulism, I gathered that pickling and preserving weren't nearly the chores I had imagined them. Ample vinegar, salt, and patience were all I needed.

Preservation methods varied with nationality. The Germans, for example, fermented their cabbage into sauerkraut while the English preferred to pickle it.

I was, after all, following in the footsteps of infinitely hardworking and patient people. Early Americans considered pickling and preserving indispensable frontier skills, the smartest way of managing their adopted land's abundance. Fish, beef, and pork they salted and smoked, vegetables they steeped in brine, and fruits of all kinds they immersed in one acidic solution or another. Their successes they published in almanacs and "agriculturals," tremendously popular publications that enjoyed wide circulation.

"For 't is always fair weather / When good fellows get together / With a stein on the table and a good song ringing clear." --Richard Hovey

These publications' popularity owed as much to necessity as anything else. Those new to the United States needed all the advice they could get. Life in America was novel in every sense, not the least meteorologically. Thunderstorms soured milk. Heat waves stunned cows. Summer frosts and winter thaws blighted crops and corrupted food stores. "So great were the contrasts between summer and winter on the East coast," remarked Englishman Charles Johnson, that "articles of life" experienced seasonal influences hardly perceptible in the British Isles. His countryman, Isaac Weld, observed that Yankee weather blew more foul than fair, Philadelphia's local climate leaving an especially strong impression on him. There the temperature could vary some 50 degrees in 26 hours. The city broiled in summer, froze in winter. Autumn and spring saw violent and sudden swings between the two extremes. "As early as the fourteenth of March," Weld notes, "Fahrenheit's thermometer stood at 65 at noon day, though not more than a week before, it had been so low as 14."

"There is a sumptuous variety about the New England weather that compels the stranger's admiration -- and regret. The weather is always doing something there; always attending strictly to business; always getting up new designs and trying them on people to see how they will go ... In the Spring I have counted one hundred and thirty-six different kinds of weather inside of twenty-four hours." --Mark Twain, "New England Weather" (New England Society dinner speech, New York, Dec. 22, 1876.)

Volatile weather spoiled food in no time. "Those who have a mind to swallow or be swallowed by flies may eat fresh meat for me," wrote a visiting Englishman of his attempt at storing lamb in summer. Poultry hardly fared better. A chicken could be killed no more than four hours before cooking, and it had to be kept in cool water until the moment it went into the oven. It comes as no surprise, then, that cookbooks preached moderation in provisioning. "[You ought] not buy too much for your daily wants," The Frugal American Housewife (1829) warns readers, "while the weather is warm."

"Boswell. 'I dined lately at Foote's, who showed me a letter, which he had received from Tom Davies, telling him, that he had not been able to sleep from the concern he felt on account of *this said affair* of Baretti, begging of him to try if he could suggest any thing that might be of service, and at the same time recommending to him an industrious young man who kept a pickle-shop.' Johnson. 'Ay, sir, here you have a specimen of human sympathy; a friend hanged, and a cucumber pickled.'" -- James Boswell, Johnsoniana, Volume 1 (1820)

Pickling and preserving preserved those who ignored this wise advice. These measures kept food edible. Sometimes they even kept it flavorful. Pickling in the United States often occasioned admirable inventiveness. Peaches, which lent themselves especially well to the process, pickle-makers pricked with cloves and dunked in sugar-and-vinegar solution; or they sliced them thin, boiled them in honey, left them in the sun to dry before packing them into pots and sprinkling them with powdered sugar. Cherries were dried, melons plucked young and covered in brine, and apricots boiled, peeled, and dunked into French brandy.

Dutch farmers made New York City home to the 17th century's largest pickle industry.

Vegetables underwent less sumptuous treatment, but they were no worse for it. Peppers became vinegar, and mushrooms catsup. Both were packed into jars for winter storage. Cucumbers were pickled in salt-brine or vinegar. "Yellow pickle," an early 19th-century Virginia favorite, featured an impressive variety of produce fermented for some 48 hours in salt water. After fermentation, it was spread on thick cloth to bleach in the sun. The bleached mixture was scooped up, dropped in a pot of vinegar and turmeric, and fermented for another two weeks. Whether any nutritional value remained to the dish is anyone's guess, but only after this laborious process was it deemed fit to eat.

Whether it grew on a stalk, dropped from a branch, walked, flew, or swam, it mattered little. If you could eat it, Americans would preserve it.

By 1870, five years after the Civil War, Americans were consuming thirty million cans of food annually

Meat they rolled in salt, sugar, and potassium nitrate and plunked in a pickling barrel. Oysters, mussels, and clams they tossed in a vinegar crock. Herring, shad, and mackerel they left to bubble in a brine that formed when salt mixed with the fish's own oils.

"Alas! my poor countrymen, how many years of calamity awaits you, before a single dish or a glass of wine will be withdrawn from the tables of opulence!" --From Pig's Meat; or, Lessons for the Swinish Multitude (1794)

Overheated, frostbitten and storm-ravaged, Americans reached for yet another preserved food to soothe their nerves -- a delicate fruit wine, perhaps, an effervescent perry, or a hearty ale. Popular cookbooks featured recipes for wine of the raisin, cowslip, and birch variety. Especially recommended came sage wine, which was purported to "cure any aches or humours in the joints," as well as "keep off all diseases to the fourth degree," banish "dead palsy, and convulsions in the sinews," and sharpen the memory. Indeed, "from the beginning of taking it," sage wine "will keep the body mild" and strengthen "nature, till the fulness of your day be finished."

The Heinz display at the Chicago World's Fair of 1893 was one of the smash hits of the fair, and was in line with Heinz's mission to market his pickles aggressively. He arranged demonstrations at grocery stores, offered a money-back guarantee, opened his factories to public tours, gave away samples, and invested heavily in the most expensive form of advertising of the time, the electrically illuminated sign.

Recipe for pickled barberries from American Cookery (1796): "Take of white wine vinegar and water, of each an equal quantity; to every quart of this liquor, put in half a pound of cheap sugar, then pick the worst of your barberries and put into this liquor, and the best into glasses; then boil your pickle with the worst of your barberries, and skim it very clean, boil it till it looks of a fine colour, then let it stand to be cold, before you strain it; then strain it through a cloth, wringing it to get all the colour you can from the barberries; let it stand to cool and settle, then pour it clear into the glasses; in a little of the pickle, boil a little fennel; when cold, put a little bit at the top of the pot or glass, and cover it close with a bladder or leather. To every half pound of sugar, put a quarter of a pound of white salt."

The fullness of home preserving's day diminished somewhat as the 19th century drew to a close. In the late 1870s, a new method of packing under steam pressure made large-scale production of glass-jarred pickles possible. A tempting array of commercial canned goods, sensational advertisements warning of germs and other nasty things, and the changing nature of work both inside and outside the home -- all compelled the housewife to lay aside her mason jars. Kitchen layouts eventually came to reflect the waning interest in home food preservation. Observers of 1920s residential architecture remarked how traditional spaces for such activities were altogether absent in new home construction.

Word has it the practice is making a comeback. I admit my own flirtation with food preservation has been a success. To date I have brined twenty quarts of dill pickles, and just last week I pickled beets. I sampled a beet yesterday, and it was tastier than anything I could have picked up at Whole Foods (and cheaper too!). Next week I'm going to try my hand at peaches. As for meat, I'm keeping mine fresh. Get carried away with home preserving and you can find yourself in a real pickle.