What made Breaking Bad's Walt so endearing was his awkward, reticent Dad love and the unimaginable lengths he went to to provide for his family. With his body count racking up, Walt’s paternal rationalization is harder to buy.

In developing his character Walter White for AMC’s Breaking Bad, Bryan Cranston told creator Vince Gilligan, “I think he should have this silly little mustache that doesn’t really convey anything, except it conveys impotence to me.” TV mustaches typically suggest libidinal sex stallion in the vein of Tom Selleck. But on Walter White’s droopy face it stood for capitulation. “It sort of was a manifestation of what I thought his life was at the time—that he felt unnecessary. That he felt useless. That he was invisible to the world and to society, basically to himself.”

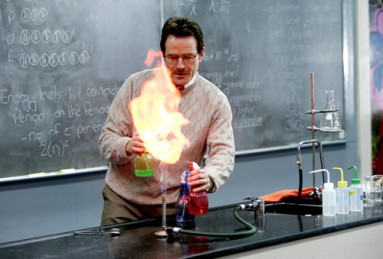

When Breaking Bad began four seasons ago in 2008, Walter White was a man degraded. His former chemistry colleagues screwed him out of his fair share of a patent and became millionaires while he taught high school chemistry and worked at a car wash after school to make ends meet. In the pilot episode Walter states plainly, “My wife is seven months pregnant with a baby we didn’t intend. My 15-year-old son has cerebral palsy. I am an extremely overqualified high school chemistry teacher, and within 18 months I will be dead. And you ask me why I ran?” Many men would have run—to alcohol, to another woman, to a coconut island, even to their untimely death; Walt became a meth-cooking drug lord. Though Walt begins from a position of degradation-- financially, professionally, and sexually (wife Skyler gives him the birthday gift of the world’s most awkward hand job while both sit erect in bed), he asserts himself as a man through his fatherhood. Over the course of the past three seasons, Breaking Bad has explored masculinity through the role of the father.

More than any show in recent history, Breaking Bad is high art on low subjects. Winning Peabody and PEN Literary awards for writing, as well as three back-to-back Best Actor Emmys for Bryan Cranston, it takes place in Albuquerque, New Mexico’s sprawl of strip malls and sub developments, in barren landscapes and motel parking lots. Wide lens shots capture high desert desolation and time-lapse photography melts the sky from morning softness to the fires of sunset to the impenetrable darkness of night, an arc the series’ plotlines mimic. The cinematography often favors extreme low-angle shots, producing the perspective of a child gazing up from a father’s knees. The story splinters off to expansive subplots: A family struggles to pay their medical bills, DEA agents pursue drug dealers who are always one step ahead, a small time dealer tries to kick addiction and get his life together. But at the center is Walt, refusing to go quietly, rebelling against the pathetic fact of his life.

Untangling the existential anxieties of middle-aged white men is a major theme in modern cable dramas like Mad Men, Big Love, and The Sopranos. But the leads in these shows are defined by, and find solace in, stereotypical expressions of masculinity: Don Draper in secretaries and scotch, Bill Henrickson in righteous peopling of the Celestial Kingdom, Tony Soprano in cigars, sports cars, and being boss. From the beginning of Breaking Bad, Walt’s masculinity is challenged. Teaching high school (a common symbol of impotence in TV shows and film) insults his abilities as a brilliant chemist, rewarding him with little money and less self-worth. And he is tired, walking hunched over, his jowls sagging, looking like he has been dropkicked through the goalpost of life. But rather than cheating on his wife or shirking paternal duties, he sees producing meth as a way to provide for his family, engage in high-level chemistry, and regain the power to choose, returning himself finally to manhood. The control, cover-up, and, ultimately, violence spark something in Walt: “For the first time in a long, long time I am not sleepwalking through life. I am awake.” He echoes Robert de Niro’s Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver, who said, “Here is a man who would not take it anymore… here is a man who stood up.” But standing up, propelled by years of percolating disappointment, and exploding into the world as a vigilante reclaiming lost dreams results in serious collateral damage.

Stepping up to paternal responsibilities is the ultimate demonstration of masculinity in Breaking Bad. In Season 3, Walt wants to emulate the soft-spoken, chicken-chain-restaurant impresario and meth-magnate Gus (Giancarlo Esposito). Gus portrays himself publicly as a local business leader and family man while running his drug ring with corporate efficiency. He convinces Walt to continue producing his signature Blue Sky meth in his megalab by preying on Walt’s desire to be the patriarch of his household. Staring at him unflinchingly, Gus says: “What does a man do, Walter? A man provides. And he does it even when he’s not appreciated, or respected, or even loved. He simply bears up and does it. Because he’s a man.” It’s a sentiment of stoic responsibility that seems archaic, unsexy, not the kind of escapist fantasy we look to Don Draper and his ilk to provide.

Other male characters in Breaking Bad play out the show’s conflicting definitions of masculinity. Hank, Walt’s DEA-agent brother-in-law, is built like a brick shithouse with the potty mouth of a frat boy. As a surrogate father to Walt Jr., Hank fulfills the machismo that Walt, because he has cancer or isn’t inclined, doesn’t. He’s also a good cop, and the show’s only consistently morally upright figure. But after being grevously wounded by an exploding tortoise in El Paso, a terroristic message from a Mexican drug lord, Hank experiences post-traumatic stress, spinal paralysis, and the loss of his identity as the ‘big man’, mirroring the experience of returning U.S. soldiers who traditionally represent this form of masculinity. In the Season 4 premiere, he crumples with humiliation as his wife helps him clean up his uncontrollable bowel movements, revealing the inadequacy of a masculine morality entirely based in physical prowess.

Aaron Paul's performance as Jesse Pinkman, the small time dealer turned Walt’s partner in crime, reveals a soft vulnerability behind the sneer of baggy jeans and skull tattoos. Despite his desire to be a hardened drug lord, Jesse is constantly reaching out to connect with other people. In Walt, Jesse sees a father and he constantly bends to Walt’s wishes as he seeks approval. Conversely, Jesse grows into his manhood whenever he has the opportunity to sacrifice himself for someone else. In the Season 2 episode “Peek-a-boo” Jesse protected the neglected child of meth heads he was supposed to kill. As his relationship with his girlfriend Jane developed, Jesse was ready to abandon his partnership with Walt. It is his desire to step up that ennobled him to kill on Walt’s behalf. He was trying to please the man he sees as his father.

As Gus asks in the Season 4 premier “Box Cutter,” “How pure can pure be?” Walt clings to his original notion that he is cornering the Southwest meth market for his family, that it is his duty as a provider. Fatherhood is merely an excuse, a story he tells himself to sanction murders and to commit them himself. Walt Jr. and Skyler become details—pesky obstacles that pull him back from full immersion into the underworld—but whenever his neck is on the line, Walt suddenly becomes a committed family man. He uses their need of him to justify placing Jesse in the line of fire instead of himself; always eager to please, Jesse bends to his surrogate father’s wishes. This fact, however, isn’t lost on Jesse, who said to Walt in Season 3, “Ever since I met you, everything I’ve ever cared about is gone.” Familial love is desperate love, and Walt leverages his power as father figure to make Jesse perform increasingly despicable acts.

What made Walt so endearing, especially compared to the many self-serving male TV protagonists, was his awkward, reticent Dad love and the unimaginable lengths he went to to provide for his family. With his body count racking up, Walt’s paternal rationalization is harder to buy. Sunday’s Season Four premier “Box Cutter” showed no hint of Walt’s good intentions. Fully invested in maintaining his place at the top of Gus’ organization, Walt shared no screen time with his son, Walt Jr., and about thirty seconds with a newly zaftig Skyler. Walt completed his transformation from man degraded to Machiavellian villain through the ordering and manipulation of Gale’s murder.

Since last season, the writers have been setting up tragedy for Walt Jr. with his driving lessons, and this will probably be the place where Walt confronts his choices as a father. The taut, deliberate editing can give future plotlines away because without filler, every scene foreshadows or resolves. In a macabre throw back to Season One, the season four premiere has Jesse and Walt dissolve yet another body in hydrochloric acid, but this time without the black-comedy pratfalls. A brief diner scene—an homage to Pulp Fiction—provided the only moment of levity in the oppressive episode, where the size sticker on Walt’s post-body-dissolving ensemble is still stuck on, a playful mark that subtly alludes to his former self, a man who was the punch line of the joke. That man is all but gone.