Hey Girl, I had a dream about you last night, we went antiquing and got your mom a really nice gift — it was pretty intense.

They were going to hurt you … I just thought you could get out of here if you wanted to, I could come with you, I could look out for you.

I’m going to help you rediscover your manhood: You’re sitting there with a Supercuts haircut, you’re getting drunk on watered-down vodka-cranberries like a 14-year-old girl, why don’t you take that straw out of your mouth?

These are among the memes and catchphrases deemed significant enough to require assignment to a vehicle capable of distributing them to the masses, to a body that lures audiences and Rachel McAdams alike, to a mouth that almost never shows its teeth when it smiles: the mouth of Ryan Gosling.

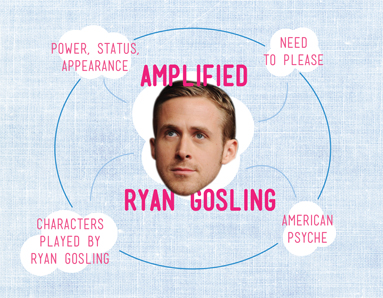

It was a shrewd choice. That Gosling has come to personify the present moment is evident not only in his Hollywood fame — he has starred in three blockbusters in the past six months and is set to appear in another three in the coming year — but also his internet fame, where he is discussed endlessly in blogs, fan sites, and countless Tumblrs devoted to Gosling-centric memes.

We should not take Gosling lightly: He has clearly struck a cultural nerve, and his performances have proven themselves to resonate deeply with the American psyche. Gosling has become the man people want to reenact their social world, the lens through which people want their experiences filtered, whether it be their romantic fantasies, their theoretical leanings, their hobbies, their entertainment, or their pancakes.

Gosling’s presence in a film assures it will be taken as an important revelation of the American zeitgeist, which in turn reinforces his own cultural significance. His fame has reached the level of tautology: It has transcended causal logic altogether, acting as a feedback loop that amplifies the ideas and cultural assumptions that he transmits. Such resonance allows his films to serve as especially effective bearers of ideology. They target psychological spots that have already been softened, bypassing rational argument to establish the sort of beliefs that can perpetuate society on its current terms.

Consider the recent film Drive, a nouveau-noir thriller in which Gosling plays a stuntman and getaway driver who, in an effort to protect his neighbor and inamorata from the thugs who would do her harm, becomes entangled in a cycle of Mafia-related violence. If that premise sounds familiar, it is because the movie fits the tried-and-true formula of patriarchal fantasy wherein viewers are asked to accept that violent death at the hands of others is the primary existential threat and, consequently, that women need male protection to survive.

Under late capitalism, the true existential threat is deprivation. Far more will succumb to a lack of food, uncontaminated water, or medicine than will be murdered. Scarcity pervades our everyday lives and terrorizes us: Even our relative opulence cannot quite suppress the mantra of “work or starve” humming quietly in the background. Capitalist society trains us to cater to capital to escape this threat, placing great value on those who are able to suck up to bosses.

Patriarchal fantasies play against this. In their contrived worlds, social value accrues to brutes who can physically overpower would-be aggressors — which is to say that men are rendered heroes by default. Hence Ryan Gosling’s character in Drive. While handsome and physically powerful, he entirely lacks personality, rarely speaking and even then only in clipped, monotonic generalities. Fittingly, the name of the character is never revealed, a seeming admission that he is less a person than an interchangeable part of the machines that he supposedly commands. He is simply the Driver, and he need not be more, as is made clear by the otherwise inexplicable romance that develops between the nameless character and his neighbor Irene (Carey Mulligan).

It doesn’t matter that Gosling’s character has the personality of a piece of toast: He is the man that can crush the skull of an aggressor lurking in the elevator. Irene is lucky to have landed such a catch. Insofar as women can be brought to believe that our world is like the patriarchal fantasy world, they will leave the theater wishing that they, too, had a Gosling to protect them, for, as sublime as it is to be independent, that freedom can’t keep you safe from the Mafia.

Recognizing patriarchal fantasy for what it is offers some protection from its seductions. Yet awareness of it threatens to lead us into the maw of another ideological monster: meritocratic realism — that what is, is fair, and that status is its own alibi. Men are not valuable for their capacity for brute violence but for the strategic ruthlessness that can secure them money and influence.

This ideology is at play in another recent Gosling blockbuster: the slickly executed (and hideously punctuated) Crazy, Stupid, Love. In this film, Gosling plays Jacob, a smooth-talking, sharply dressed tomcat who tries to help cuckolded Cal Weaver (Steve Carell) by teaching him the art of the pickup, training him to dress fashionably, drink like an alpha male, and make woman-pleasing small talk. “Be better than the Gap!” Jacob commands, urging Cal to ditch the suburban wear and New Balances that, from the opening scene, have emblemized Cal’s distance from respectable masculinity.

Jacob’s status as an alpha is never in question. He has his pick of the women in any given room, and Cal physically submits to his dominance on multiple occasions: Jacob repeatedly slaps him for transgressing various rules of fashion, eliciting little more than a whimper from Cal — and continued compliance. Yet the foundation of Jacob’s high status is not his ability to physically subdue others but his ability to satisfy their desires. While Irene gives her body to the Driver so he’ll protect her, Cal submits to Jacob because Jacob can pander successfully to women and manipulate them for sex. Jacob is socially useful only insofar as he dresses in ways that women find pleasing, speaks in a way that entices them, and has a body that looks like it’s been Photoshopped for maximum sex appeal.

But if these underpinnings of Jacob’s preeminence were explicit, they would cast doubt upon its legitimacy. Social dominance generally depends on the perception that the alpha is an ontologically superior being capable of shaping the social world at whim. Yet Jacob is not an Übermensch but its antithesis, no more than a servile flatterer willing to conform to others’ whims for a buck or, in this case, a fuck. Jacob is an impostor masquerading as a king.

Who is Jacob, really? His wardrobe, haircut, muscled body, charm, and conversational style are nothing but calculated attempts to accommodate others. Jacob has given up everything about himself to get female affection. Conditional love has left him little more than a shell, his personality and aesthetic totally flattened by the societally imposed need to please. He is someone who simply cannot afford to be himself, for the cost of rejection — going without love or companionship — is far too great.

But we cannot laugh at the emperor’s nakedness without indicting ourselves. This same bootlicking ability underlies almost all economic power under capitalism whereby we achieve “domination” only through submission, “predominance” only through compliance. Excluding inherited wealth, one can become rich only by identifying some need and satisfying it for money. Just as Jacob must bend over backward for women in order to seem dominant, one must willingly commit completely to catering to the whims of others if one aspires to be wealthy. Only by perfectly conforming to their fantasies — and thereby abandoning the self — does one become Hollywood and internet famous.

Crazy, Stupid, Love paints the gloss of ontological superiority onto those most willing to embrace the humiliations of conditional exchange. Just as Ayn Rand used her angular magnates to romanticize those who do the economic bidding of others, the film uses Gosling to glorify sycophancy in the realm of the social. The film asks us to admire him, but really we ought to pity him, for he is a broken man, one whom we should ache to welcome into our arms with the assurance that here he will be loved for who he is. Here he will be loved because he, too, suffers as we do. That we make him into memes is perhaps a tacit recognition of this humanity: Our desire to see him embody our slogans emerges as much from empathy and communal understanding as it does from reverence.

There is a little bit of Jacob in all of us. It is in his image that we come to hide our tattoos from our bosses, our politics from our lovers, and our histories from our friends. Even our smallest details are revised, replaced by those that can better please powerful others. And so we advance through our lives, always keeping our teeth carefully hidden when we smile.