Francesca Borri's Syrian Dust

IT was the faux pas heard around the world. When US libertarian presidential hopeful Gary Johnson was asked what he would do about one of the most dire humanitarian crises of the 21st Century, even the hosts were stunned. “What is Aleppo?” How could a person run for the highest office in the land and not know about this place that had over the last 6 years come to represent every limit, failure and shortcoming of contemporary conflict management and international politics?

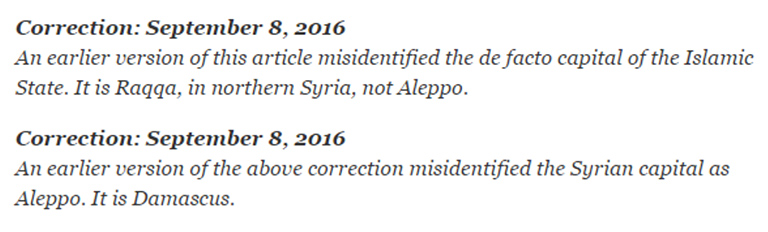

And yet, Johnson was far from the only person in the USA with this particular ignorance. In an article intended to chastise Johnson for his ignorance, the New York Times was forced to correct itself, not once, but twice which only made the newspaper seem ill-informed as well.

What is Aleppo? is one question, to which we might add, why is this even a question?

In her newly translated book, Syrian Dust, Francesca Borri has answers.

For a start, Aleppo is ugly, bloody evidence of our collective failure to give the idea of “humanity” any meaning beyond the barest rhetorical flourish. With sometimes painful clarity, Borri shows that Aleppo is every broken promise, bundled lie, and double standard implicit in the mantra “never again.” Aleppo is our collective failure to know, care, or understand. Aleppo is everything that’s wrong with what “humanity “is today.

It’s no surprise that those who don’t care don’t know. Who is shocked that the libertarian candidate is fuzzy on foreign policy? Such disregard is almost woven into the libertarian’s political isolationism; a week later, Gary Johnson struggled to name a single foreign leader he admires, and joked that he was having an “Aleppo moment.” This city, synonymous with collective failure to empathize, has become a rhetorical dismissive shrug. But Johnson isn’t the only one having “Aleppo moments.” What do we make of the fact that those who presumably do care—who believe themselves knowledgeable and authoritative, like the “paper of record”—seem to imagine that they know so much more about Aleppo than they actually do?

Borri has answers here too. For her, Aleppo is not a moment, but the culmination of many choices: a refusal to understand the Middle East beyond tropes; an unwillingness to effectively reform the international humanitarian system; and a lazy, un-creative journalism all conspire to create the “Aleppo Moment” we’re living in. Not an unwillingness to remember but an inability to engage, leaving thousands to suffer unnecessarily. It is a reckoning with everything the humanitarian system developed in the post-war environment promised but failed to become.

BEFORE 2011, Aleppo was Syria’s largest city and one of the largest in the region with a population of 2.13 million people. It was one of the oldest continually inhabited cities in the world and listed as one of UNESCO’s World Heritage Sites. For as many regime changes and conquests as there have been in the region, over the last four millennia, there has always been a settlement in the town currently known as Aleppo. Layers of Roman, Byzantine, Arabic, Sumerian and other historical civilisations are knotted together in the city’s architecture, food, music and character. Aleppo is the story of the evolution of the modern city.

Estimates of the city’s remaining population are difficult to come by, but perhaps 60 percent of the city’s population remains, divided between the rebel-held east and the regime-held West, with pockets of intervention by Al Qaeda and its affiliates. After four years of war, the city’s remaining residents—especially the estimated 300,000 in the rebel-held east—aren’t so much living as existing. Every day, they are dodging mortar showers, evading ghoulish militants of all stripes, scavenging for rats and addled by preventable diseases; those who remain in Aleppo hold on to their survival by their fingernails. There is only one functional hospital left in Syria’s largest city, and it is in the West, where civilians have to brave snipers, airstrikes, and mortars if they try to leave.

Everything about Aleppo screams urgency, but our ability to listen or look depends on a series of gatekeepers, a network of interests and the ways in which we are conditioned to digest and process news from faraway places. You can’t know Syria if the people you look to for information about Syria are themselves biased or beholden to interests that do not want you to know. You can’t think independently if you’ve never been pushed to digest information independently, and you probably haven’t. But even if you had, what could you then do with all that information besides worry yourself into an early death?

Borri gives us the story of an unravelling country as witnessed by those left behind. By shifting the central narrative object of her analysis away from power – looking away from governments and politics to the individuals who suffer the consequences of choices made at that abstract level – she allows us to see how the concessions we make to power have produced an inherently unstable and dangerous international system. For example, bookshelves around the world are filled with misguided accounts of ancient rivalries and religious animosities in Syria, but such stories (as Borri demonstrates) have more to do with the analyst’s biases than any reality on the ground; what analysts itch to present as “ancient rivalries” are simply modern negotiations between various groups in the name of exigency or military advantage. Some rebel leaders in Raqqa are Christian and some are Alawite, Assad’s own community; in Daesh-held Raqqa, “rebels control the areas with the wells, the regime controls the areas with the pipelines…And so, for once, the regime and the rebels reached an immediate accord. Sunnis and Shiites.”

The war in Syria is the product, simply, of a global political system that privileges profits, that sells obscene quantities of arms to bloodthirsty tyrants and an international system that too beholden to the powerful nations that profit from this trade ever to challenge this system. Consider Borri’s account of the evolution of the Arab spring, where she observes:

“the main supporter of the rebels in Syria – the main supporter of democracy – is Saudi Arabia. Which doesn’t even have a real parliament, and which I’ll never be able to write about because to go there I need a male guardian. So either find me a husband who will take me there on a leash, or I will never be able to tell you about this country, champion of freedom in Syria.”

It’s not that other journalists have not made connections between the revolution in Syria and international geopolitics. It’s that few point out how absurd these connections are. But Borri spares no sentiments; she’s not interested in making conciliatory noises at Russia or the US or Iran or Saudi Arabia. She is interested in painful realities like “the sole area of Aleppo that has never been bombed is Al Qaeda’s headquarters.”

Borri isn’t interested in what the war looks like from the boardrooms of the UN headquarters in New York, from the many failed negotiations in Geneva, or from the gore-thirsty newsrooms of international media. And so we are reminded that even while the UN stopped keeping track of the number of those killed, each number has a name, a history and a family attached to it. That no matter how many bombs drop from the sky, hope – that poorly defined impulse that persists in the face of unbelievable odds – will keep people like The White Helmets rushing towards the rubble to try and pull out another child.

Bringing the entire edifice of contemporary conflict into close scrutiny, Borri includes the humanitarian community that continues to debate and discuss Syria… without Syrians. The UN’s conferences, prizes and meaningless admonitions are a repeated target of scrutiny in this book:

“I am in Berlin for a prize,” she writes, “which for 2012 obviously goes to a photograph of Syria because what could be more dramatic than Syria this year? Even though, truthfully, neither UNICEF nor the UN have ever been seen in Aleppo.”

Working at the frontline of the Syrian conflict has eroded Borri’s faith in the international architecture that she once studied closely. Prior to dodging mortars in Aleppo as a freelance journalist, Borri used her two Masters degrees, in international relations and human rights, working with various NGO’s in the Balkans and in the Middle East. It’s not clear what prompted the change, but the influence of her prior work is apparent in her unwillingness to catalogue anything but the entirety of her subjects experience.

Borri focuses on repeated failure of UN convoys to deliver aid to besieged communities, like those in Aleppo, because of the existing statutory framework that compels them to keep working with the regime. It recently emerged, for example, that the UN was found to be collaborating with the Damascus regime even as the same regime starved hundreds of thousands in a deadly network of sieges in Yarmouk, Daraya, Madaya, Aleppo amongst others. The same with other major humanitarian organisations that have avoided going into Syria, preferring instead to remain in the periphery (and thereby helping only a subset of people who had the financial wherewithal to flee). Where humanitarian actors do proactively intervene, they are exposed to grave risks because of information shared with the regime, as when Russian airstrikes destroyed a Red Crescent convoy led by the Syrian director of the organisation in September, even though the Red Crescent had shared details of the humanitarian convoy’s trajectory.

The media is also a target for Borri. There were broadly three categories of journalists in Aleppo when Borri arrived: the staff reporters at major international newspapers, who jetted in for a day or two and then left; the freelancers who stuck it out for several months, and the Syrian journalists who are openly partisan but who continue to be the only major source of information in Aleppo. But it’s never that there isn’t news about Syria, it’s that someone with the power to decide what makes the paper thinks you don’t want to read about Syria (or has strong opinions about how). This dynamic gives gatekeepers tremendous power to shape perspectives and responses. And as gatekeepers have become more focused on what gets attention—rather than what sustains it—the media has become a bloodthirsty monster, feasting on human misery and regurgitating gore in pursuit of eyeballs and profit. Is it a wonder that fewer and fewer people are reading traditional newspapers when we only get blood, guts, and destruction? We read stories about displaced people eating grass to survive in Yarmouk; we read very little about who these people are. “If you only talk about those who fight,” Borri offers, “every revolution becomes a war.”

This state of affairs leads to absurdities. Borri recalls sitting in an abandoned building in Syria while mortars rained overhead and an editor emailed to ask if she was one of the Italian journalists who was recently kidnapped. Not out of concern for her wellbeing: the editor wanted her to tweet about her captivity to draw more attention to the paper.

In this framework, expertise is dependent on who knows whom in the editorial room rather than who is actually in the know; instead of measured, nuanced critique, we get speculation and misguided book-learning:

“‘Read this analysis from the front!’ the US State Department tweeted excitedly yesterday. It was a piece by a young reporter already quote[d] by the Washington Post and the Economist as an expert on Islamic militant groups, and in particular on Jihad in Syria. Then a reporter called him for an interview. He’s twenty-one years old and studied literature at Oxford. He’s never been to Syria.”

Borri argues that the media—obsessed with clicks per minute, shares and likes—is complicit in oversimplifying and abstracting warfare into power games between men. But she also argues that we the audience are equally complicit for failing to challenge the gatekeepers and to demand something closer to the truth. If we refuse to understand that Syria is not Iraq, and that Iraq is not Afghanistan, and that each nation and each war has a history that doesn’t fit neatly into whatever paradigm suits our intellectual agendas, then we beg to be spoon-fed what we already think we know: that there’s always a good guy and a bad guy and that if the good guys just had more guns then none of this would be a problem.

One of the most notable casualties of the Syrian war is the idea of international humanitarianism itself. How can we believe that “never again!” means anything if thousands of people starve to death every day, and not because there is no food, but because there is insufficient will to get it to them? What does it mean to have a “responsibility to protect” when every possible intervention on behalf of Syrian people is sacrificed at the altar of state sovereignty? International humanitarian law tells us that certain spaces are inviolable, but over a hundred hospitals have been deliberately targeted in this war.

Syrian Dust is Borri’s first book translated into English, and one can only hope to see her other two books translated too. As a female war correspondent in a male-dominated profession with a background in humanitarianism, Borri is a triple outsider, and she raises the possibility that the entire edifice through which we respond to war is no longer fit for the purpose. If we follow Borri down the Syrian rabbit hole we see how tenuous our beliefs about conflict are. War strips humanity of any niceties, and shows us in our worst light; against the triumphalist genre of war literature, which finds heroes amongst the rubble, Borri focuses on a harder truth: war is ugly, tremendously painful, and profoundly unrewarding for the vast majority of those who live it. There is no glory in the rubble: only the stench of untimely death.