Unterzakhn, Yiddish for “underthings,” opens with a slap to a child’s face, and as her cheek swells, a woman lays dying in the street, blood staining her skirt. The year is 1909 and in the teeming dirt streets of New York’s Lower East Side, twin sisters Esther and Fanya Feinberg run errands for their mother, feed fish heads to a gang of mangy cats, and chase after their little sister Feigl. Shopkeepers and neighbors gossip loudly behind each other's backs, haggle and glare. Fanya is haunted by nightmares of women puking up babies, while her sister dreams of bracelets and lace. Author and artist Leela Corman draws a stark, childlike world — never innocent or nice — in thick black brushstrokes, reminiscent of the work of artists Joann Sfar and Marjane Satrapi. Unterzakhn intriguingly captures a fictional 20th century world mediated through multiple lenses — the reformer’s camera, the historian’s archive, and ultimately Corman’s imagination and pen. This isn’t quite history documented, or even historical fiction; it is more an alternate reality, a totally accurate other New York.

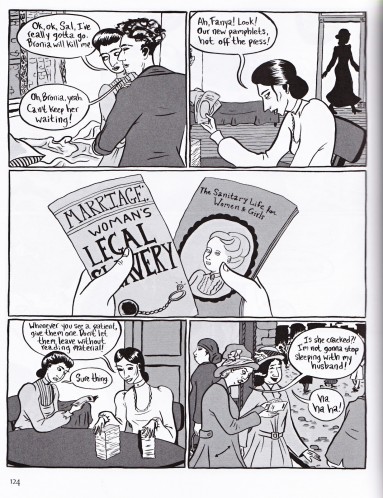

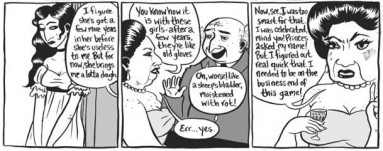

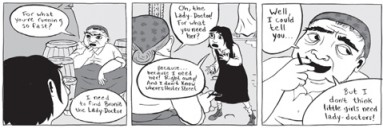

The beginning, with Esther and Fanya as young girls, is when Corman’s illustrations and sparse dialogue best carry the story. The twins try to make sense of burgeoning adulthood and the complicated rules and social codes they’re meant to follow, clinging together in the wake of distant and cruel adult interactions. Their adulterous mother brandishes kitchen implements and warns, “Just you wait. One day, it’ll be you up here, slaving away for your own army of little ingrates!” Their alcoholic father tells them Greek myths in Central Park while dreaming of his life and family lost to Cossack raids in Russia. When Esther and Fanya emerge from their tenement childhood into complicated adult lives, one as an actress and prostitute, the other as a birth control crusader and illegal abortionist, Corman’s energetic brush becomes oddly droll, her lack of exposition confusing. Unterzakhn threatens to slip into what the Yiddish theater would classify as shund, soap-operatic and chintzy, with a hipster flair for seedy establishments and flapper dresses. Fanya has an affair with a childhood friend and gets pregnant, while providing illicit birth control and anti-marriage literature to her patients. Esther lives in a penthouse apartment furnished by a wealthy patron, starring in vaguely pornographic stage productions. The two don’t speak until they are brought together again by tragic loss — their sister hit by a streetcar, their mother dead of the Spanish flu — only to encounter more of the same. The characters melodramatically dance around one another with sideways glances in a series of overly layered vignettes separated by splash pages and spot illustrations — a poster of Esther starring in the show Salome, a pickle in a puddle of brine, a never-ending sky of laundry lines strung between tenement windows, jackboots marching onto the fields of the First World War.

Corman enlists a sort of Dora the Explorer Yiddish — a word thrown in here and there for flavor — which does less to ground the reader in Jewish New York than create an unintentional comic relief, perhaps because of the pop-culture training of Seinfeld and generations of Jewish comedians “oy”-ing their way into the spotlight. And yet I couldn’t help but be a little in love with the black-eyed sisters, whose divergent paths engage a prevailing feminist narrative of reproductive rights and sexual freedom, the struggle of access to family planning and self-determination. Esther and Fanya both push back against compulsory marriage and motherhood in their own complicated and sometimes unintentional ways, in a nascent feminist world populated historically by figures like Margaret Sanger and Emma Goldman, and fictionally, Corman’s “lady doctor” Bronia.

With Unterzakhn, Corman follows in the footsteps of a pretty heavy-hitting body of Jewish graphic novels, including Will Eisner’s seminal A Contract with God, also set in tenement New York. Corman also, perhaps unintentionally, engages a burgeoning, growing movement among young secular Jews attempting to reconstitute Yiddishkeit as an authentic site of Jewish identity. After a century of cultural annihilation and assimilation — through pogroms and genocide, the Soviet Union’s decimation of Jewish intellectuals, emigration, Israel’s ban on Yiddish theater in the 1950s — Yiddishkeit stubbornly clings to life.

In an interview with The Jewish Daily Forward, Yiddishist Rokhl Kafrissen writes:

At my Conservative Hebrew school Shma [a principal religious prayer] and Hatikvah [the Israeli national anthem] were given equal weight … The State of Israel, we were told, was the home of the Jewish people and Europe was a continent sized graveyard ... What we did learn didn’t quite track with the lived Jewishness all of us, teachers and students, brought into the classroom.

Kafrissen’s experience matches mine and, I’m sure, the experiences of many Ashkenazi Jews in the United States. If one believed our Hebrew School educations, what Yiddish culture didn’t burn with Tevye’s village burned with the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory. And Jewish food is falafel and “Israeli salad.” The project of creating a Jewish state in Palestine has necessitated the erasure of Yiddishkeit, a flattening of Ashkenazi tradition as well as the more violent and racialized erasures of Sephardic and Mizrahi life in favor of a monolithic Israeli culture and language. We are not meant to remember where our grandparents came from, only Abraham and Isaac.

Out of this confusing black hole of Jewish cultural education, Unterzakhn, whether or not it's shund, is a thread of connection in a growing and varied bundle, documented for example in Vlada Bilyak’s brilliant blog and radio show Ekh Lyuli Lyuli. Unterzakhn speaks to the urge to reconstruct Yiddish histories, from the tattered rags of anecdotes told over and over again by refugee grandparents, from the stories of Shalom Aleichem and the Hollywood versions of Fiddler on the Roof and Yentl, from the 10 Yiddish words every Ashkenazi grandchild knows how to mispronounce and misuse. Kafrissen continues, “in the language and culture of Ashkenaz I found everything I had once assumed Judaism simply didn’t have: songs for every occasion, dances other than a zombified hora, and a radical history very much of use for the present.”

A reinvigorated Yiddishkeit presents a more compelling birthright for a present in which American Jews are beginning to question our own Israeli nationalism en masse — both affiliation as well as economic and political support for the state of Israel — and its varied implications. In the face of disciplinary rhetoric of “self-hatred” from groups like AIPAC, a growing movement of Diaspora Jews is questioning the elision of our ethnic histories, the conflation of Jewish religious identity and a Zionist politic, the false assertion, as sociologist W.M.L. Finlay points out, that “Jewish criticism of Israeli policy is ... a turning away from Jewish identity itself.” Could it be that Israel is just another state, with a bloated military and horrific human rights record, a penchant for building illegal settlements and apartheid walls, deporting refugees, and exiling indigenous peoples?

A 2007 study titled “Beyond Distancing: Young Adult American Jews and Their Alienation From Israel,” by Steven M. Cohen and Ari Y. Kelman, found that American Jews under the age of 35 have significantly less emotional attachment to the state of Israel compared with previous generations. Cohen and Kelman recommend “promoting trips to Israel,” such as the revealingly named Taglit-Birthright tours, as “the most policy-relevant action organized Jewry can undertake to stem the erosion in Israel attachment among younger adult Jews.” The study expresses concerns about interfaith marriage and conflates alienation from Israel with alienation from Judaism. Alternately, the organization Jewish Voice for Peace (JVP), through a campaign called “Young, Jewish, and Proud,” names the alienation of Jewish youth in the Jewish establishment’s overemphasis of Israel and its inability to address the oppression of Palestine, rather than a lack of access to free trips to Israel filled with camel rides and Dead Sea salts. Through disentangling nationalist imperative from ethnic heritage, one finds spaces in which to foster an affective need for Jewish religious observance and community, to interrogate the simultaneous investment in and pushing back against the yearning for a mythic homeland that pervades diasporic identity.

The desire to keep Yiddishkeit alive signals less nostalgia than a political urgency grounded in a cultural history of resistance--a need to discover a relevant, lived Jewishness not over-invested in the propaganda of a dubious and oppressive “homeland.” In the language and stories of the Old World, young Jews may be able to carve out a way of being Jewish both in the New World of the United States and the new world our radical Jewish ancestors dreamt of in the pages of the anarchist weekly paper Fraye Arbeter Shtime. As Esther teases Fanya, “sometimes you sound just like the pamphlets those grubby young men hand out in the park!” More than a love letter to a distant Yiddish past, the fiction of Unterzakhn might open, for some readers, a historical crease in which to dream both of the other New York of Corman’s pen, and other worlds that might be possible.