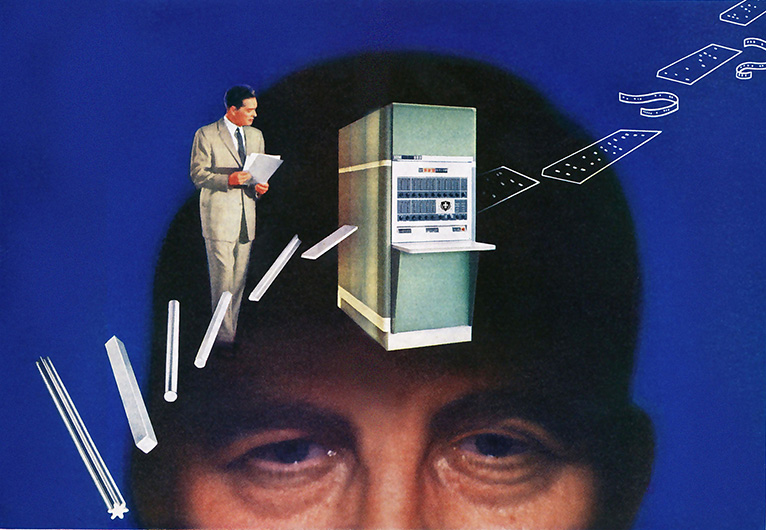

We are being seen with ever greater resolution, even while the systems around us increasingly disappear into the background.

ON November 7, 2016, the day before the US Presidential election, the New Inquiry recorded a Skype conversation between artist and writer Hito Steyerl and academic and writer Kate Crawford The two discussed NSA bros, dataveillance, apex predators, AI, and empathy machines. This is the first in a two-part series. The second part of the conversation, which takes place after the election, will be published in February.

KATE CRAWFORD. Hito, we met during the time we were both working with the Snowden archive--shall we talk a little about what our respective experiences were like?

HITO STEYERL. For me the experience of working with the archive was very limited. I was looking for a very simple example, and I only ended up writing about a single image that was published on the Intercept. It’s a single frame of scrambled video imagery, and I tried to connect that with some of the metaphors that the analysts themselves use to describe the job they are doing in SIGINT Today, published on the Intercept.

I used a couple of their metaphors, namely, the “sea of data” they described--which you also used, Kate, in your essay for the Whitney--to try to think through the sinking feeling of basically being surrounded by this data.

KATE CRAWFORD. What I loved--going back to our panel at the Whitney and thinking about your “Sea of Data” piece--is that we both hit on these singular images about the limits of knowing. For you it was that grainy capture of video. For me, back when I was writing for the New Inquiry in 2014, I was fixated on this image, which had been redacted, that simply says, “What can we tell?” and it’s effectively a blank space. It has that double meaning that you and I have both found very intriguing: the idea that they could tell and see everything, but also that there are domains where they can tell and see nothing. There are these hard limits that are reached in the epistemology of “Collect it all” where we reach a breakdown of meaning, a profusion and granularization of information to the point of being incomprehensible, of being in an ocean of potential interpretations and predictions. Once correlations become infinite, it’s difficult for them to remain moored in any kind of sense of the real. And it’s interesting how, for both of us, that presents a counter-narrative to the current discourse of the all-seeing, all-knowing state apparatus. That apparatus is actually struggling with its own profusion of data and prediction. We know that there are these black holes, these sort of moments of irrationality, and moments of information collapse.

HITO STEYERL. Blind spy.

KATE CRAWFORD. Yes, exactly. And it’s funny, too, because in addition to the kind of sinking feeling of the sea of data, there’s also this kind of humor in its construction. For me, certainly, in the work that I was doing in the Snowden archive, it presented a vast maze to try and negotiate…

HITO STEYERL. But how was it?

KATE CRAWFORD. I had some of the worst nightmares of my life over the months I was working in that archive. And it was physically draining. But the thing that got me through were these moments of humor. It’s very dark humor, but in the archive there are so many moments of this type. Some of the slides in particular are written in this kind of hyper-masculinist, hyper-competitive tone that I began to personalize as “the SIGINT Bro.” There’s this “SIGINT bro” voice that would be like, “Yeah, we got ‘em! We can track anybody! Pwn all the networks!” But it has an insecure underbelly, a form of approval-seeking, “Did we do good? Did we get it right?” And that figure, that persona, weirdly kept me going because it just seemed so human and so fallible.

HITO STEYERL. I think you brought it up beautifully in your presentation: the almost emoji-like type of cartoon-like figures that are being used, all these images of Weatherby, for example, and magic, that abound in the initial unconscious of the archive. That’s rather funny.

KATE CRAWFORD. I think there’s a considerable archival unconscious in there that would take us a long time to unpack. The other thing that I would love to talk to you about--and this is switching from the state to corporate uses of data, because I know both you and I are interested in how those two are really merging in particular ways--is IBM’s terrorism scoring project, which I have spoken about elsewhere. I know we are both interested in how this type of prediction is a microcosm of a much wider propensity to score humans as part of a super-pattern.

HITO STEYERL. I’m really fascinated by quantifying social interaction and this idea of abstracting every kind of social interaction by citizens or human beings into just a single number; this could be a threat score, it could be a credit score, it could be an artist ranking score, which is something I’m subjected to all the time. For example, there was an amazing text about ranking participation in jihadi forums, but the most interesting example I found recently was the Chinese sincerity social score. I’m sure you heard about it, right? This is a sort of citizen “super score,” which cross-references credit data and financial interactions, not only in terms of quantity or turnover, but also in terms of quality, meaning that the exact purchases are looked into. In the words of the developer, someone who buys diapers will get more credit points than someone who spends money on video games because the first person is supposed to be socially “more reliable.” Then, health data goes into the score--along with your driving record, and also your online interactions. Basically it takes a quite substantial picture of your social interactions and abstracts it into just one number. This is the number of your “social sincerity.” It’s not implemented yet--there are some precursors in the form of extended credit scores which are already being rolled out--but it is supposed to be implemented in 2020, which is not that long from now. I’m completely fascinated by that.

KATE CRAWFORD. What’s interesting to me when I think about the Chinese citizen credit score is that here, in the West, it gets vilified as a sort of extremist position, like, “Who would possibly create something so clearly prone to error? And so clearly fascist in its construction?” Yet, having said that, only last week we saw that an insurance company in the UK, the Admiral Group, was trying to market an app that would offer people either a discount on their car insurance or an increase in their premium based on the type of things they write on Facebook. Fortunately, that was blocked, but similar approaches are already being deployed. The correlations Admiral was using were things like if you use exclamation marks or if you use words like “always” and “never,” it indicates that you have a rash personality and that you will be a bad driver. So if you happen to be someone who uses emojis and exclamation marks, you will be paying more to insure your car. This seems very similar to a type of citizen scoring that I think has permeated at the molecular level in so many parts of life throughout the US. It’s too easy for Americans to point to China and go, “Oh, it would never happen here.” But in a much more dispersed, much harder to detect manner, these things are already starting to become a part of how lives are being predicted, insured, and rated. In many ways, I see it as very banal; the Chinese credit score has already happened. It’s already here, regardless of where we are citizens.

As for the IBM terrorist credit score, there are two aspects that really stay with me. One is the fact that it’s being tested and deployed on a very vulnerable population that has absolutely no awareness that it is actually being used against them. Two, it’s drawing upon these terribly weak correlations from sources like Twitter, such as looking if somebody has liked a particular DJ, and conjecturing that this person might be staking out the nightclub where they play. These are, I think, far-flung assumptions about what the human subject does and what our data traces reveal. To use Jasbir Puar’s concept of “the trace body,” the assumptions that go into the making of the trace body have become so attenuated and, in some cases, so ridiculous, that it’s critically important that we question these knowledge claims at every level.

HITO STEYERL. This reminds me of the late 19th century, where there were a lot of scientific efforts being invested into deciphering hysteria, or so-called “women’s mental diseases.” And there were so many criteria identified for pinning down this mysterious disease. I feel we are kind of back in the era of crude psychologisms, trying to attribute social, mental, or social-slash-mental illnesses or deficiencies with frankly absurd and unscientific markers. That’s just a brief comment. Please continue.

KATE CRAWFORD. Actually I was about to go exactly to the history, so your comment is absolutely dead-on. I was thinking of physiognomy, too, because what we now have is a new system called Faception that has been trained on millions of images. It says it can predict somebody’s intelligence and also the likelihood that they will be a criminal based on their face shape. Similarly, a deeply suspect paper was just released that claims to do automated inferences of criminality based on photographs of people’s faces. So, to me, that is coming back full circle. Phrenology and physiognomy are being resuscitated, but encoded in facial recognition and machine learning.

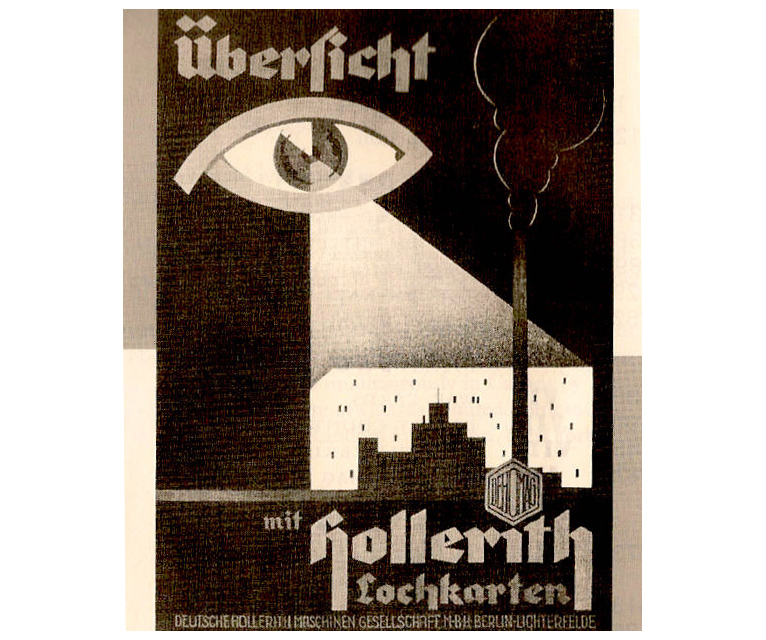

There’s also that really interesting history around IBM, of course back in 1933, long before its terrorist credit score, when their German subsidiary was creating the Hollerith machine. I was going back through an extraordinary archive of advertising images that IBM used during that period, and there’s this image that makes me think of your work actually: it has this gigantic eye floating in space projecting beams of light down onto this town below; the windows of the town are like the holes in a punch card and it’s shining directly into the home, and the tagline is “See everything with Hollerith punch cards.” It’s the most literal example of “seeing like a state” that you can possibly imagine. This is IBM’s history, and it is coming full circle. I completely agree that we’re seeing these historical returns to forms of knowledge that we’ve previously thought were, at the very least, unscientific, and, at the worst, genuinely dangerous.

HITO STEYERL. I think that maybe the source of this is a paradigm shift in the methodology. As far as I understand it, statistics have moved from constructing models and trying to test them using empirical data to just using the data and letting the patterns emerge somehow from the data. This is a methodology based on correlation. They keep repeating that correlation replaces causation. But correlation is entirely based on identifying surface patterns, right? The questions--why are they arising? why do they look the way they look?--are secondary now. If something just looks like something else, then it is with a certain probability identified as this “something else,” regardless of whether it is really the “something else” or not. Looking like something has become a sort of identity relation, and this is precisely how racism works. It doesn’t ask about the people in any other way than the way they look. It is a surface identification, and I’m really surprised how no one questions these correlationist models of extracting patterns on that basis. If we harken back to IBM’s Hollerith machines, they were used in facilitating deportations during the Holocaust. This is why I’m always extremely suspicious of any kind of precise ethnic identification.

KATE CRAWFORD. And that was precisely what the Hollerith machines did across multiple ethnic groups.

HITO STEYERL. If one takes a step back, one could argue that we need more diverse training sets to get better results, or account for more actual diversity on the level of AI face recognition, machine learning, data analysis, and so on. But I think that’s even more terrifying, to be honest. I would prefer not to be tracked at all than to be more precisely tracked. There is a danger that if one tries to argue for more precise recognition or for more realistic training sets, the positive identification rate will actually increase, and I don’t really think that’s a good idea.

Let me tell you a funny anecdote which I’ve been thinking of a lot these days: I’m getting spammed by Republicans like crazy on my email account. I’m getting daily, no, hourly, emails from Donald Trump, from Eric Trump, from Mike Pence, from basically everyone, Newt Gingrich--they are all there in my inbox. And I have been wondering, why are they targeting me? It really makes no sense. I’m not even eligible to vote, but I went to Florida recently and I think something picked up my presence in that state and combined it with my first name, coming to the conclusion that I must be a Latino male voter in Florida. So now I’m getting all these emails, and I’m completely stunned. But I prefer to be misrecognized in this way than to be precisely targeted and pinpointed from the map of possible identities to sell advertising to or to arrest.

KATE CRAWFORD. There is something fascinating in these errors, the sort of mistakes that still emerge. These systems are imperfect, not just from the level of what they assume about how humans work and how sociality functions, but also about us as individuals. I love those moments of being shown ads that are just so deeply outside of my demographic. Now Google has been giving people who they think are American prompts to go and vote tomorrow in the election. I’m getting that every time I check my mail. Of course, I’m not an American, I’m an Australian--I have no right to vote in the American election--but I’m getting constantly prompted to do so every day. Google has so much information about me--there’s absolutely no question that it knows that I am an Australian --but that connection between its enormous seas of data and actually connecting that to instrumentalize the knowledge is still very weak.

What you’ve hit on is a fundamental paradox at the heart of the moment that we are now in: if you are currently misrecognized by a system, it can mean that you don’t get access to housing, you don’t get access to credit, you don’t get released from jail. So you want this recognition, but, at the same time, the more the systems have accurate training data and the more they have deeper historical knowledge of you, the more you are profoundly captured within these systems. And this paradox--of wanting to be known accurately, but not wanting to be known at all--is driving so much of the debate at the moment. What is the political resolution of this paradox? I don’t think it’s straightforward. Unfortunately, I think the wheels of commerce are pushing towards ‘total knowing,’ which means that at the moment, although we see these glitches in the machine, they are very quickly getting better at doing that kind of detection.

There are so many ways we can be known. They are imperfect and they’re prone to these strange profusions of incorrect meaning and association, but, nonetheless, the circle is getting closer and closer around us, even while the mesh networks of capital are getting better at disguising their paths. I know you’ve also been thinking about crypto-currencies and what remains hidden and what is seen. Or take artificial intelligence. Artificial intelligence is all around us. People are unaware of how often it’s touching their lives. They think it’s this futuristic system that isn’t here yet, but it is absolutely part of the everyday. We are being seen with ever greater resolution, but the systems around us are increasingly disappearing into the background.

HITO STEYERL. I really love the beginning of the text I was just reading when you called, “Artificial Intelligence Is Hard To See.” As you say, it’s the “weak AI systems” which are currently causing the most severe social fallout. I absolutely agree with this. I call these systems “artificial stupidity” and I think they are already having a major impact in our lives. The main fallout will of course be automation. Automation is already creating major inequality and also social fragmentation--nativist, semi-fascist, and even fascist movements. The more “intelligent” these programs become, the more social fragmentation will increase, and also polarization. I think a lot of the political turmoil we are already seeing today is due to artificial stupidity.

KATE CRAWFORD. It’s interesting because in my work I’ve been thinking about the rise of the AI super-predator. The narrative that’s being driven by Silicon Valley is that the biggest threat from AI is going to be the creation of a superintelligence that will dominate and subjugate humanity. In reality, the only people who would realize that this is already emerging are the current apex predators themselves. If you are a rich white man who runs a major technology company or a venture capital company in Silicon Valley, the singularity might sound very threatening to you. But to everybody else, those threats are already here. We are already living with systems that are subjugating human labor and particular subsets of the human population in ways that are harsher than others.

So one of the things that is going to happen in the US is the complete automation of trucking. Now, trucking is one of the top employers in the entire country, so we’re looking at the decimation of a dominant job market. But if you replace truck drivers with autonomous trucks, you still need someone to protect the freight loads. That means some people will still be hired by this industry, but they might be hired as security labor. Categories of work change, and humans will be closely enmeshed with autonomous machines. At a highly skilled level, this will mean designing new AI systems. But for other people, it’s just about providing physical muscle. We need to be attentive to the shifts in how we think about human labor in this rush to automation.

HITO STEYERL. As people get replaced by systems, one of the few human jobs that seems to remain is security. I just went into a supermarket in Holland and there was literally no cashier left, just a security person. All the female cashiers--it used to be a female job, mainly--were now being replaced with just one security guy. It was kind of extraordinary.

KATE CRAWFORD. In the long tail of human labor, the last remnant will be security. The security guard will be the last person to leave the building.

HITO STEYERL. It’s like low-grade military.

KATE CRAWFORD. It reminds me of a joke that you told a long time ago when we were talking about the singularity. I was talking about my apex predator theory and you said, “You know, people think that this superintelligence is off in the future, but it’s already here. It’s called neoliberalism.”

HITO STEYERL. But it is, no?

KATE CRAWFORD. I love that joke. It’s my favorite Hito joke.

As I was reading your work again this morning, I was going back to what you wrote about the idea of the comrade, and I was thinking about the value of comradeship. What does it mean to be comrades in this field of machine vision and autonomous agents? Can an idea like that persist in these spaces? Where do you find comradeship?

HITO STEYERL. This is definitely one of the assumptions that’s thoroughly lacking in the development of all of these systems. Today I was reading a very interesting research paper about computer-based social simulations. They made this agent who is quite humanlike in that he is not rational--he has emotions and so on--but anytime they let it loose, it would start killing. They start killing one another very quickly. They can’t survive. It’s pure genocide. And I think the reason--I have no idea--but I expect one of the reasons for that was that they did not manage to formalize empathy and solidarity. There is probably a formula that they use for homophily, or preferences based on affinity. But homophily is not solidarity, and I really wonder how these systems would look if anything like that was introduced. They would probably look very different, but we don’t know. Until then, all these simulations are presented as scientific renditions of human behavior.

KATE CRAWFORD. I often think about this concept of solidarity in a world where so many of these stacks that overlay everyday interactions are trying to individualize and hyper-monetize and atomize not just individuals, but every sort of interaction. Every swipe, every input that we make, is being categorized and tracked. The idea, then, of solidarity across sectors, across difference, feels so powerful because it feels so unattainable. Maybe that’s its power--that it seems outside of these models of data capture and social modeling.

HITO STEYERL. Have you seen any example of an AI that was focused on empathy or solidarity? Do you see the idea of comradeship anywhere in there?

KATE CRAWFORD. I go back to the beginning. I go back to Turing and to even the early Turing test machines, like ELIZA. ELIZA is the most simple system there is. She is by no means a real AI and she’s not even adapting in those conversations, but there’s something so simple about having an entity ‘listen’ and just pose your statements back to you as questions. People found it incredibly affecting. Some thought that this could be enough to replace human therapy. But there were these hard limits because ELIZA couldn’t actually empathize, it couldn’t actually understand, and I don’t think we’ve moved as much as we think since then. ELIZA as an empathy-producing machine because she was a simple listener. She wasn’t trying to be more intelligent than her interlocutors, she was just trying to listen, and that was actually very powerful.