In his 1918 volume of criticism, The Delicious Vice: Pipe Dreams and Fond Adventures of an Habitual Novel-Reader Among Some Great Books and Their People, Young Ewing Allison offers an assessment of Wilkie Collins’s 1859 thriller, The Woman in White. Allison confesses a particular fondness for the character Count Fosco, whom he considers “the villain par excellence of novels.”

As villains go, Count Fosco certainly cuts one of literature’s more striking figures. “[I]mmensely fat” and bearing the “most remarkable likeness, on a large scale, [to] the Great Napoleon,” he also boasts “unfathomable” eyes that possess an “irresistible glitter.” Other parts of the count’s visage “have their strange peculiarities”: “a singular sallow-fairness,” characterizes his complexion, which contrasts strikingly with “the dark-brown colour of his hair” that suggests to onlookers a wig. Despite such peculiar features, however, the count is not unpleasant to behold.

And Count Fosco proves as unexpectedly spry as he is attractive. He moves in a way “astonishingly light and easy,” passing through rooms “as noiselessly as a woman.” He startles as easily as a woman, too.

The count’s delicate nerves do not prevent him from delighting in all sorts of small creatures. To indulge his violent love of animals he keeps “a cockatoo, two canary-birds, and a whole family of white mice.” The cockatoo “rubs its top-knot against his sallow double chin” and the mice, who reside in “a pagoda of gaily-painted wirework,” crawl over him, “popping in and out of his waistcoat, and sitting in couples, white as snow, on his capacious shoulders.” The absurd disparity in his size with that of his playmates’ is lost on him; he finds “nothing ridiculous in the amazing contrast between his colossal self and his frail little pets.”

When the delight of frolicking with his pets wears thin, the count feasts on large fruit tarts, which he inundates with jugs of cream. “A taste for sweets,” he proclaims in his “softest and tenderest manner,” is nothing but “the innocent taste of women and children,” the sharing of which he considers “another bond, dear ladies, between you and me.”

This bond no doubt extended to Allison, who appraises Collins’s thriller in decidedly gustatorial terms. “‘The Woman in White’ is the best novel in the world to read gluttonously at a sitting and then forget absolutely,” he writes. “When the world is dark, the fates bilious, the appetite dead and the infernal twinges of pain or sickness seem beyond the reach of the doctor, ‘The Woman in White’ is a friend indeed.”

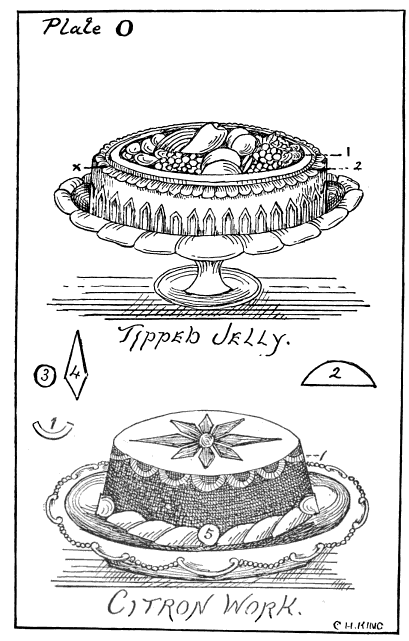

Of course no appetite should be so dead as to be beyond the reach of the mammoth fruit tarts that Count Fosco loves so much. The 1864 manual Cookery for English Households presents a recipe for one such dessert, which surely must rate among the best laid plans of mice and men when it comes to creating sensations.

Tartes aux fruits — Prepare a paste … for the bottom of the tart; all around the edges place a small ribbon of puff paste … nicely cut out with a paste-cutter; fill up the inside of the tart with cherries previously stoned and drained upon a tammie; keep the juice. Sprinkle some sugar over the fruit, and set the tart in the oven. When well raised and quite firm, add the juice; and when the tart is to be served, sift pounded sugar over it. Large fruit-tarts require half an hour’s baking.