Women’s sexual pleasure has rarely been treated as an appropriate subject for economics. Various political theorists have long ruminated on the dubiousness of even naming women’s sexual pleasure as though it were transhistoric: “Sex-negative” and “sex-critical” feminists consider, for instance, to what extent such a thing is even possible under white capitalist patriarchy. Conversely, materialist- and trans-feminists radically torque and historicize the term “women” (e.g. are lesbians women?), and gay communists question the assumption that female pleasure, putative or no, is necessarily distinct from other people’s. In contrast to this kind of queer utopian and feminist-materialist theorizing, Kristen R. Ghodsee’s book Why Women Have Better Sex Under Socialism: And Other Arguments for Economic Independence takes the categories “women” and “good sex” to be robust, measurable sociological variables tightly linked to (also measurable) human happiness. The evidence for its titular claim consists of the suite of pre– and post–Cold War studies that showed how Soviet East Germans were scoring far higher than the West Germans on “happy women” metrics, including sexual satisfaction. The Eastern Bloc, in short, was suspected of having a higher (female) Gross Domestic Orgasm. It is for this reason (in an only slightly tongue-in-cheek sense) that the book by Ghodsee, recently released by Nation Books, argues for an American “socialism.” It recommends that free-market democracy in the United States be ameliorated with the help of soft, Scandinavia-style, social-democratic policies geared toward “economic independence” of the citizen and the nation. For Ghodsee, mining the Stalinist past for not-so-bad ideas is basically a necessary exercise in liberal broad-mindedness.

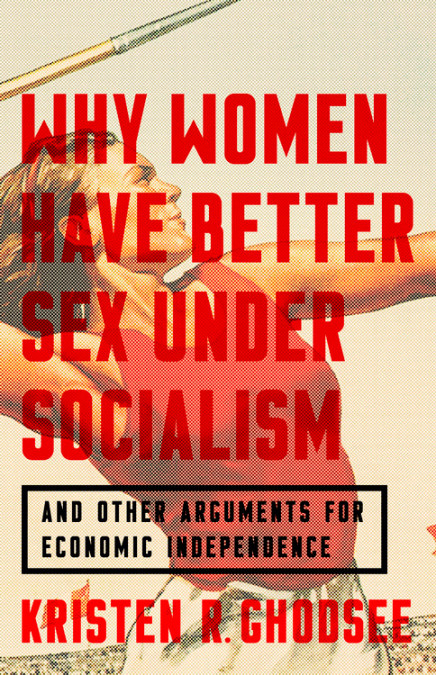

Kristen R. Ghodsee, Why Women Have Better Sex Under Socialism: And Other Arguments for Economic Independence. Hachette/Nation Books, 2018. 240 pages.

Once I’d finished reading it, I mulled over Better Sex Under Socialism while watching a movie about a love affair between two queer journalists in Budapest in 1958, Egymásra nézve, translated into English as “Another Way.” Though made in 1982, director Károly Makk’s movie takes place in the aftermath of the communist workers’ council rebellion and the brutal Soviet deployment of tanks to Budapest to suppress it. The lovers in the movie, Éva and Livia, are understandably depressed but irreducibly corporeal, passionate, mutual-aid-oriented people who still believe in an uncorrupted communism. They take pleasure in life in manifold ways, eating, drinking too much cognac, conversing heatedly with others, walking in the woods, and refusing the spineless collaborationism and corruption of the other journalists and civil servants around them. Though they suffer police repression (Soviet cops catch them making out on a park bench), betrayal from supposed comrades, near-fatal domestic violence from Livia’s husband, and, ultimately (spoiler alert!), fatal state violence, Another Way makes me yearn, with its unruly protagonists, for a world in which not only capitalism and bureaucracy but marriage, the institution of the family, and compulsory heterosexuality have been abolished. Recalling so many family-abolitionists and “free love” utopianists in history, the refusal of relationship and identity categories in Another Way points toward the creation of conditions under which categories like “lesbian” and even “sex” might fall away.

Wiping the tears from my face as the credits rolled and returning to my heavily annotated copy of Better Sex Under Socialism with newfound skepticism, I realized that the source of my dissatisfaction might run deeper than the fact that Ghodsee barely once mentions lesbian desire. Rather, it’s her neglect of the question upon which everything (for anti-Stalinist communists) depends: the question of what an anti-capitalist, non-capitalist, post-capitalist society worthy of those names might actually look like. In its centering of that question, after all, Another Way echoed the argument in Shulamith Firestone’s 1970 manifesto The Dialectic of Sex, that the Russian Revolution failed because it failed to abolish the nuclear heteropatriarchal family. In a genuinely revolutionary society, Firestone had contended, “sexuality would be released from its straitjacket to eroticize our whole culture, changing its very definition.” Hannah Proctor paraphrases: “Intimacy, comfort, arousal, support, tenderness, affection, stimulation, laughter, intensity, and companionship might be diffused throughout life, not cloistered away in private fleeting moments between individuals.” What would “better sex” even mean in a situation like this, where the boundaries of sex have become somewhat more doubtful?

But in the context of United States public discourse, even these disavowals are not enough to save the author from being tarred as an authoritarian Communist in the center-right and alt-right media. Imagine the hate mail Ghodsee received for her article in the New York Times centenary feature on the Russian Revolution, “Why Women Had Better Sex Under Socialism.” The Washington Examiner’s indignation constituted perhaps the most hilarious public response. “Are women in Venezuela having great sex right now?”—well, even if they are, “people have more sex during blackouts,” which are “quite common due to state ownership of electricity companies.”

Indeed, a surprising level of defensiveness still circulates in capitalism’s heartlands in response to this infamous evidence, collected decades ago, suggesting East German women were experiencing twice as many orgasms as West German ones. The ensuing meme of the sexually emancipated “Ost-Frau” still inflicts a sting in the First World.

Inadequate as the methodology clearly was, whereby “good sex” was correlated to high orgasm-output, the results visibly still have the power to disquiet and infuriate. How could this possibly have been true, American patriots ask themselves, fretfully—what with freedom and democracy and sex toys on one side of the wall and a one-party state on the other?! (Ghodsee also thinks sex-toys are uniquely capitalist.) Was sowing this unease the whole point, originally? Was the whole exercise—or, at least, the promulgation of its findings—devised to generate geopolitical ressentiment? At any rate, as historian Dagmar Herzog notes, East German experts endlessly reiterated their GDR-vindicating conclusions. Perhaps inevitably, Ghodsee has been painted as a Cold Warrior anachronistically joining in this nationalist baiting.

It is reasonable to infer, even from the past-tense version of her statement linking “socialism” with women’s pleasure, that Ghodsee wants socialism in America, and soon. Again, right-wing opponents of socialism were always going to extrapolate the least defensible, least historically contingent, version of the claim, in bad faith. But note that the constative historical statement “Women Had Better Sex Under Socialism” in Ghodsee’s original Times title has now evolved—in the hands of Nation Books—into an even more confident prescriptive: Women Have Better Sex Under Socialism.

So, had or have? In both cases, a welter of objections spring to mind. I don’t mean the obvious one: namely, “where was, where is socialism?” My questions, to name a few, are: Who made (or makes) the woman under socialism erotically happy? Was it predominantly her own good self, or other women, singly or in groups, or—unlikely as it may seem—individual men? Secondly, what got (or gets) her off? And is (or was) this “better sex” actually good sex, or still, conceivably, worse for women than no sex at all? Does frequency or duration or location or the presence or absence or intensity or number of orgasms really have anything to do with the goodness of sex? For that matter, can the quality of sex be quantified at all?

“First of all,” retorted Ghodsee in summer 2017, “I did not come up with the headline.” Nevertheless, by keeping—intensifying, even—that clickbait headline, and emblazoning it on the cover of her new book, she is compounding the flagrant invitation to misinterpret her scholarship she professed, last year, on her blog, to so regret. While her claim is actually merely that gender pay-equity, humane divorce law, decent childcare provision, and so on “produced especially charmed conditions for mutually satisfying heterosexual sex,” you can see why Ghodsee, in choosing her title—which, as Charlotte Shane points out, is ultimately “a cynical marketing ploy”—might think to herself, “Hey, in for a penny, in for a pound.”

But her willingness to cherry-pick from the Soviet policy pantheon is, more than anything, supposed to prove Ghodsee’s fervent Americanism, her freedom from dogma. “Not all who fought or found themselves on the left side of history were radical Marxist zealots bent on world domination,” she offers, generously, in The Left Side of History (2015). By the same token, when she notes (in Better Sex) that in contemporary right-wing discourse “women’s rights and entitlements are painted as part of a coordinated plan to promote world communism,” she regards seeing the goals of feminism and anti-capitalism as dovetailing in this way as ridiculous. The existence of “leftist millennials” in the U.S.—like me—who do assert this, and who want “full communism now” (small c) (ibid.), frankly, horrifies her. Surely, our proposals must be a “joke.” But grappling seriously with the question of how to avert any repetition of Stalinism on earth is, in reality, hugely important to me and my peers because we know in our bones that anti-capitalist revolution is absolutely necessary for the future of life.

So what does Ghodsee stand for? For “citizens” to “get wise and start going to the polls” so as to “nudge things in a more progressive direction,” redeeming America, safeguarding liberal democracy, and fending off the Handmaid’s Tale scenario in which women are electorally disenfranchised and stripped of their credit cards en masse. As she remarks at the close of Red Hangover (2017), we obviously shouldn’t foment a revolution, but “we do need to start having a serious conversation about how to make democracy great again.” This phrase sounds a particularly dud note given her near-complete silence on the question of race in America, and her uncritical shout-out (on page six of Better Sex) to Sahra Wagenknecht, promoter of the 2018 fascist-wooing turn in Germany’s Die Linke party.

But what conveys the content of Ghodsee’s feminism most effectively is the cumulative impression left by the profiles of the author’s friends. “Jake,” the Reaganite/Thatcherite corporate executive and “childhood friend” we meet in chapter two, tells Kristen over the phone, “I’m never hiring a woman again”—and somehow remains her friend. “Ken,” the “alpha male” in chapter four and five whom Ghodsee euphemistically calls “an economics major” while disclosing the sad fact that he “lost his life on September 11, 2001,” dehumanizes women. Then there is “Lisa,” the author’s shopping-spree companion, a high-flying San Francisco executive who quit to become a stay-at-home mom—and “claimed this was her choice.” By way of justification for this phrase’s passive skepticism, Ghodsee relates an anecdote far more horrifying than she seems to realize, one I would personally have framed in terms of abuse, exploring the scope for comradely feminist intervention and a solidarity imperative. Ghodsee is visiting Lisa, and finds that marriage has turned her into an indentured sexualized laborer who “receives no wages.” “Bill,” who thinks that he and his wife “don’t have enough sex,” unilaterally controls and delimits Lisa’s spending, prevents her from owning a bank card, and “only gives [her] cash.” After a “stunned” Ghodsee silently pushes her friend’s sole $20 bill back across the table at a restaurant, putting down plastic “in her own name” to pay for their dinner, Lisa says: “I’ll fuck him tonight and pay you back tomorrow.”

In this moment, Ghodsee offered Lisa no further aid, and indeed offers her readers no interim or grassroots-level strategies—only top-down macro policy-level ones—for supporting women of any social class in exiting structurally violent situations such as Lisa’s. And to my immense consternation, she ends the chapter with a speculative prediction containing the fantasy that Lisa and Bill will stay together:

Some day in the near future, Bill may be begging a computer to give him his Friday night allowance so he can head to the sports bar with his buddies. There will be some cosmic justice when Siri informs Bill that he’s already watched enough sports this month, and should stay home and spend some quality time with his wife and daughters.

Look, I’m as much a fan as the next commie millennial of imagining lurid scenes of revenge perpetrated upon planetary class enemies. But even on the pleasurable (albeit nonrevolutionary) terms of vengeance, I struggle to see how time spent with Bill could ever be “quality time,” or how “justice”—cosmic or otherwise—is served in a situation where Bill is being forced to . . . hang out with . . . us.

The solution Ghodsee proposes is, however, consonant with the sense one gets that when she says, “Yes, the glass ceiling needs to be broken . . . [but] policies to help women get to the top always must be combined with practical steps to help those women struggling at the bottom,” she isn’t really thinking of women situated outside of labor markets, doing unpaid work inside homes. Instead of looking at social reproduction and production as an integral whole, Ghodsee seeks to construct a dichotomy between a state-socialist mode of life where the private sphere is somehow kept “non-economic,” and a capitalist one, where said private sphere has been almost entirely subsumed into “economics” (symbolized by sex work). It is never explained why, in order to erect this dichotomy, Ghodsee is adopting the most elementarily anti-feminist assumption of classical political economy—namely, that what makes something “economic” is the presence of a wage. She simply establishes that “socialism” was characterized by despotic state surveillance and coercion and also—oxymoronically—private human fulfillment and happiness, and that free-market societies, conversely, involve anxious freedoms and “discrimination against women workers.” But hey, no state violence or coercion.

The sweet spot therefore, it is consistently argued, is a somewhat socialist-feminist “yet” not overly authoritarian society. Yet? Indeed, Ghodsee often repeats this syllogistic link, this notion of “downsides” to both components, in order to establish the desirability of a “trade-off” between wellbeing and freedom. In other words, the zero-sum linkage is naturalized the better to insist that a reasonable balance can be struck. Thus, for example: “We shouldn’t have to live under authoritarian regimes to have loving relationships based more on mutual affection than material exchange.” Ghodsee naturalizes a logic of scarcity, extending to the domain of citizens’ rights the neoliberal idea that there ain’t no such thing as a free lunch (i.e. the loss of democracy is the price you have to pay for women’s liberation).

For over a decade, some people have even set themselves up as “sexual economists”—attempting to transpose these supposed market “laws” onto the ensemble of phenomena known as sex. What is “sexual economics theory”? Better Sex makes it painfully clear that Ghodsee is in somewhat of a love-hate relationship with it. The basic idea is one she says, dizzyingly, holds “true” under capitalism. A 2004 paper, “Sexual Economics,” by Roy Baumeister and Kathleen Vohs, set forth the foundational framework, which is specifically not a theorization of the sex industry. Rather, it is an account of unwaged sex that sees sex as a nonlabor commodity: a nonrelational, quantifiable, and consumable resource some might call “pussy.” In its own words, it holds that noncommercial (heterosexual) “sex is a female-controlled commodity because . . . of the principle of least interest.” Women (cis heterosexual ones, it apparently goes without saying) therefore “suppress the sexuality of their fellow sellers,” via slut-shaming, “in an attempt to keep the price of sex high,” shoring up their own (and only) power while handily also giving (cis hetero) men, who have to work to afford this high price, an incentive and purpose in life.

If we follow Ghodsee in averring that there is “truth,” no matter how contingent a kind of truth, in the sexual-economics model, there are several premises we must accept. First, we can’t disagree all that much with the assumption that “women’s sex drives are weaker than men’s” (even though that is nonsense). Second, we have to accept the idea not only of a non-labor-based commodity but of a sex-price set by nature—set by men’s gaze itself—since for Baumeister and Vohs, “the price of sex varies with the perceived desirability of the woman offering it.” How else would this unimaginably complex metric manage to achieve an equalized aggregate of varying tastes, rendering the desires of woman-desirers fungible and modulating them according to geopolitical trends? Third, we must bracket the sex industry and throw its workers under the bus. “Many will argue that there’s nothing morally wrong with sex work,” states Ghodsee backhandedly, but it “is not sex-positive empowerment for women.” (Who really argues that work is empowering, though? Not any sex workers that I know of.) Ghodsee has said in an interview that “sex work is work,” but nothing about her intervention suggests she has integrated that knowledge into her thought. She is neither able nor willing to center sex workers qua sex workers as part of the constituency of working-class women.

Unsurprisingly, the question of sex work is, in the end, what exposes the contradictions in Ghodsee’s dichotomized public/private schematic most decisively. For simplicity’s sake, Ghodsee would have us “set aside the people who would choose sex work without economic necessity” and feel positively about the fact that surveys of Communist East Europeans suggested they “abhorred” prostitutes more than almost any other social group, so opposed were they to the commodification of something so intimate. The unraveling continues as the reader is told that the concrete example of “the good life” (in terms of staving off the predations of sexual economics theory) is: contemporary Denmark. As readers may have guessed, Ghodsee is over-extending, here, a famous 2013 article, “Cockblocked by Redistribution,” by Katie J. M. Baker. In this justly renowned piece, Baker skewered certain implications of the argument proposed in the popular paperback Don’t Bang Denmark by men’s rights activist Daryush Valizadeh (a.k.a. Roosh V). This screed, Don’t Bang Denmark: How to Sleep With Danish Women in Denmark (If You Must), to give it its full title, is one among many in a series of Lonely Planet–esque “bangs”—that is, rape guides (e.g. Bang Colombia)—aimed at the nascent “incel” market. While most of the outputs of this franchise constitute how-to-bang guides, this one was remarkable not only for recommending not to “bang” but also for its awestruck description of the feminist effects of the welfare state. Essentially, Roosh here was signaling to would-be Pickup Artists all over the world not to bother pursuing an entire (Danish) female population.

Billed as Roosh’s “angriest book,” Don’t Bang Denmark proposes that one simply cannot get laid in Denmark because, as he learned in Denmark, women’s susceptibility to predatory persuasion is inversely proportional to the degree of social welfare they enjoy. In other words, as Baker extrapolates, “marginalized women who need male spouses to flourish might find pick-up artists alluring,” whereas empowered women in social democracies are less tractable regarding rape-oriented coercion. (While I highly rate Baker’s journalism, the words “flourish” and “alluring” risk suggesting that undocumented, impoverished, disabled, migrant, trans, and racialized women somehow take joy in incels on the prowl. Alternatives might have been: “survive” and “tolerable.”) Sex work isn’t work, for Ghodsee; rather, it is by definition the worst possible sex. This conforms with her (once again sex-economistic) hunch that “because men aren’t paying for it, they perhaps care more about their partner’s pleasures.”

All in all, it is no wonder that Ghodsee doesn’t mention Denmark’s famously sizeable, reasonably safe, and semi-decriminalized sex industry. It is a massive problem for her account. Theoretically, “in societies with high levels of gender equality,” as she puts it, “women’s sexuality would cease to be a saleable commodity at all.” Theoretically, by spending relatively generously on parental leave, housing for single parents, childcare, social security, divorce provision, and reproductive rights, Denmark ought to have already partially decommodified sex. But . . . it hasn’t. Nor (relevantly—and unfortunately) has left struggle in Denmark yet abolished capitalism.

As I’ve said, the data at the heart of Better Sex Under Socialism—at least, the data undergirding its title – is academically well-worn. It will already be familiar to anyone who has seen the sharp and entertaining documentary film Do Communists Have Better Sex? [Liebte der Osten anders?], a blend of purpose-built cartoons, talking heads, and archival footage of “Ossi” family nudism, “Wessi” sex-ed, parent-teacher meetings, and DIY pornography. The director of that documentary, André Meier, moves beyond the numerical dimensions of the “orgasm war” to make the argument that Eastern heterosexuality thrived, unlike the West’s, precisely because it “had no cult of the orgasm.” Ossies, he avers, spoke far more freely and frequently than did their counterparts about their experiences and desires around sex, again perhaps because of rather than despite lacking access to pornography.

I do not contest the argument, advanced by scholars including Ghodsee, Herzog, Kurt Starke, Ingrid Sharp, Kateřina Lišková, Josie McLellan, and Paul Betts, that the lesser degree of commodification of human sexuality in the GDR played some kind of role in ostensibly straight people’s self-reporting as leading perfectly contented sex lives. I have no squabble with the basic insight that “when women enjoy their own sources of income, and the state guarantees social security in old age, illness, and disability, women have no economic reason to stay in abusive, unfulfilling, or otherwise unhealthy relationships . . . [they don’t] have to marry for money.” But I nevertheless do not share this school’s degree of enthusiasm for the relative pleasantness of Eastern Bloc heterosexuality; nor do I understand its lack of attention to queer subjects and its lack of curiosity about the post-gender horizons, the generalization of eros throughout the culture dreamed of by family abolitionists and sexual utopianists like Firestone. And I certainly do not feel, as do so many of those who pass as “revisionist” within American Russianism, that “better sex” represents the one mitigating feature of the failure that was Communism.

More than anything, then, what I object to is the anti-utopianism of Kristen Ghodsee’s approach. We can do better than a feminism that is marriage-naturalizing, anti-communist, pro–“economic independence,” yet tacitly opposed to sluts. The literal translation of the Hungarian title of my commie lesbian movie, I notice, is not actually Another Way but For One Another. And it really is for one another—including the possibility of sexual ecstasy, yes, but also a few other things as yet un-dreamed-of—that people everywhere band together and demand the impossible.