Face-covering vexes geopolitical divisions and reads as one thing: anti-American

Boston is a city perennially self-conscious about public art. A 2012 Boston Phoenix cover story examined why such an alarming number of young artists leave a city ranked in the top 10 for national arts funding. (The Boston Phoenix itself folded not long after that publication.) When it comes to large-scale works in the public domain, the city tends to favor exogenous creations rather than the homegrown. The accusation that the city is risk-averse and WASP-y descends from what Michael Braithwaite called an “age-old attitude central to the very culture of Boston itself: a city where philanthropy as historically been dedicated to institutions and fine art, rather than to visual art and artists that push boundaries.” More important, the elimination of rent control by voter referendum in 1994 ensured that tenable housing for artists, the vast majority of whom piece together low wages, would be dispiritingly low.

The most publicly discussed artwork on the heels of that 2012 report was “The Giant of Boston,” a large mural by Os Gêmeos (Portuguese for “the twins”). Otávio and Gustavo Pandolfo are Brazilian brothers from São Paulo who co-produce all their work, both sanctioned and illicit, as the eponymous twins, signing their entire jointly bred oeuvre as a single artist. Os Gêmeos’ local work comprised three murals around the city and an exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art, the most prominent artistic institution in Boston.

The story of how the brothers’ first major solo showcases in the United States came to be located in the city reveals little of substance about Boston’s conservative art fixtures themselves. After all, the commissioned works by the artists were generously funded by multiple senior, prestigious institutions. The twins are internationally hailed (their presence was described by the Boston Globe as “kind of like the Rolling Stones coming and giving a free concert on the Greenway”), thus a less “controversial” choice in and of themselves, even though they originate from—heaven forbid—a Latin American nation.

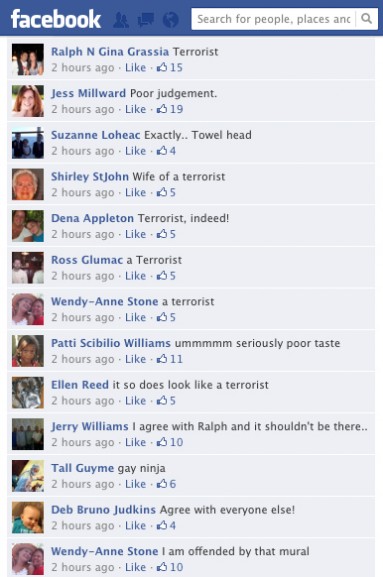

Despite the great care taken to select bonafide art stars and avoid anything “overtly political” (as curator Pedro Alonzo commented), the Dewey Square mural managed to strike a ripple of trouble. The story is said to have unfolded like this. Fox News posed a question to its online audience, encouraging viewers to air their thoughts on the station’s Facebook page: “This is a new mural on a Big Dig ventilation building. What does it look like to you?” The Facebook comment thread has since been removed, though some screen grabs remain. In great numbers, spectators explicitly likened the mural’s subject to a terrorist.

The bright-yellow, head-wrapped figure in the mural was interpreted by hundreds of Bostonians as an al-Qaeda operative, Bart Simpson disguised as a mujahideen fighter, the wife of a terrorist, a “towel head Islamist holding a gun,” an “allah [sic] loving united states hating individual,” a “gay ninja,” a Taliban fighter, a “tribute to Obama’s birthday,” and in “seriously poor taste.” The Pandolfo brothers rejoined that their effigy was a boy wearing pajamas and clothing around his visage. Lest it be claimed that the public comments were cherry-picked, Metro Boston reported that the post spawned more than 600 racially centered or bigoted comments. The ACLU of Massachusetts intervened to caution against the impulse to “equate all head coverings with terrorism.” The deadly shooting of a Sikh temple in southern Wisconsin by a self-avowed skinhead had taken place just one day earlier.

Perhaps the most honest and frank exchange about the mural took place between a child and a reporter:

CHILD: It’s scary like a Batman.

REPORTER: Why is it scary?

CHILD: Because it has something covered. And its nose is covered with a blanket.

The “controversy” surrounding the figure in the mural should not be dismissed just because it appears wholesale-manufactured by a baiting local Fox News station. An op-ed by the ICA’s current director, Jill Medvedow, claimed that “the critical issue raised by Os Gêmeos’ mural is not an aesthetic one; rather I believe it is an issue of the media declaring a controversy rather than reporting on one.” By default that claim dismisses the porous political frontiers between aesthetic choices in art and the sphere of public life (and curiously so, for artists whose work has been politically charged since its inception on the streets). Whether or not Medvedow intends it, the statement diminishes the value of the work as little more than a brightening rejuvenation of the drab downtown financial district.

Moreover, while the most obvious parts of the controversy between the art institutions backing the artwork and the artwork’s detractors staged themselves in the city, the unseen/unseeable and unspoken/unsayable relationship between the artwork and its spatial site was omitted from the discussion.

Back in 2011 the Occupy Boston (OB) popular assembly chose Dewey Square as the site of their encampment. OB never sought explicit permission to occupy the wide patch of grass in the shadow of the U.S. Federal Reserve from Dewey’s private proprietors, the Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy Greenway Conservancy. In October 2011, on the heels of police warnings of a first raid, the Rose Kennedy issued a statement: “No one asked for permission. No one gave permission.” That initial nonparticipation, which was later rescinded, seemed an implicit go-ahead while encampment was still a part of OB’s main strategy.

Leaving aside the smaller mural at the luxury boutique Revere Hotel—formerly the Charles Street jail—or the collaborative mural with RYZE, Todd James, and Caleb Neelon in Union Square, the Os Gêmeos mural in Dewey Square received explicit permission. In addition to the private funding that afforded its creation, cooperation between the Massachusetts Department of Transportation, the Boston Art Commission, and the City of Boston sanctioned the use of the front-facing ventilation building in Dewey Square. The permit proved a painless formality.

The city of Boston failed to discuss what public discourses are allowable, seeable, and sayable. A counterargument might defend the poor patches of grass and shrubbery the Conservancy cited in its protectionist pamphlets during the OB debacle, but it is clear that the city veritably bent backward to approve this privately funded, publicly displayed artwork and did not allow ventilation issues to get in the way. One might say that art is politically innocuous (and the ICA director implied as much in declaring the mural a manufactured noncontroversy). It is permissible to say so. Yet implicit in that assertion is a resignation. One must resign oneself to a certain kind of everyday nihilism: People were beaten and forcefully expelled from a narrow geography of grass that now boasts a mural from one of the most famous art collectives in the world, and in the end, it did not matter.

***

I take no pleasure in making a distinction between The Giant of Boston mural itself and the significance the artwork engendered (or failed to engender) in its current location. Inadvertently journeying alongside a fellow traveler, I have tracked the cartoonish, bright-yellow Os Gêmeos icon from the cool safety of museums to outside the statuesque walls of the Teatro Municipal in São Paulo to a few subway stops away in Dewey Square. At each site—private or public, indoor or outdoor, small-scale or large—the figure at the center of their work resonated with a complicated emotional mixture of jubilation and mourning.

The Pandolfo brothers themselves have declined (rather wisely) to discuss The Giant of Boston mural or its chosen location, save for a memorandum that they believe in “peace” and “imagination.” The crouching, face-covered yellow boy epitomizes the seedling of dissent and in that sense the mural seems to speak (though its mouth is obfuscated) for itself, whether or not the artists directly address the fact that the repression brought to bear on Dewey Square has been re-signified by his presence.

The question of the semiotic effect of the masked figure remains, and that is what aroused the ire of hundreds (and at least one young Batman-fearing boy) when they described the little giant as a terrorist. The effect differs not only transregionally (the brothers have painted several murals but this is the first in the U.S.) but also transculturally. What does the covered face of a lone figure mean in Brazil versus Boston? Why this specific figure in an American mural as opposed to other very recent Os Gêmeos creations, such as their collaborative work with Aryz in Lodz, Poland?

Locally, Mayor Thomas Menino infamously railed during the OB encampment that he would “not tolerate civil disobedience in the city of Boston.” The term anarchist was thrown in as a hooliganist slur, as it cyclically is, to encode lawlessness, mayhem, and general disarray. At least since Seattle 1999, political activists of all ethnic and class backgrounds faced suspicion, and occasionally arrest, for masking their faces. Covering one’s head or face arouses deep and immediate suspicion in contemporary society. Think of the use of head covering for religious—particularly Islamic—observance. Think of the use of face covering in strict interpretations of Islamic practice. Think of Trayvon Martin in his “street” clothes, blamed postmortem for his own death because of not only being black but having also worn a hoodie.

In Brazil face coverage highlights two things: the importance of not being identified (in a police-media alliance where the arrested are widely filmed and photographed, their images distributed as mug shots on national television before so much as a formal accusation) and a way to draw attention to the invisibility of the poor. This is not a matter of inference: Os Gêmeos have explicitly questioned the Brazilian flag’s motto (drawn from French positivist Auguste Comte) of “order and progress” in their images. Their yellow and brown animated figures wearing tattered clothes and covering their faces are inconvenient thorns to a long civilizational project.

The overwhelmingly negative disposition toward the mural reveals how Latin American and Middle Eastern visual typologies of face-covering— the disregarded poor of Brazil, the Zapatistas of Mexico, the fedayeen of Palestine—collapse into a muddled sameness in the eyes of a suspicious beholder. The racial and sartorial coding that vexes geopolitical divisions reassigns them as one thing, and one thing only: anti-American.

This tendency to see only the repetition of the covered face (repetition because it resists representation) lends not only to the erasure of history, particularly the revolutionary movements of the 1960s and ’70s, but to the equation of the masked face with lessened humanness. Viewed this way, one can see how The Giant of Boston can simultaneously be aggregated with a negative-marked identity (“towel-headed terrorist”) and emptied of political agency (an occupier in the shadow of the Federal Reserve building).

Now that the mural is going to be prematurely pulled down—many months shy of its original 18-month designated time frame and for reasons unconvincingly given—it seems appropriate to revisit the rancor-inducing icon after the Boston marathon bombing. An unorthodox view of history might cast the mural as inadvertently prefiguring a great local terror. That the terror was masked—though the violent diegesis allegedly staged by the Tsarnaev brothers never involved a masked spectacle—speaks more to the contours of American imaginations about occluded “others” than it does about art. That the artwork was able to shed light on such leanings—that it acted as a surface on which deeply lodged wishes and fears materialized—was its greatest intervention.

The Rolling Stone profile of Dzhokhar Tsarnaev made mention of two kinds of inscriptions on walls. The first was inside the boat where Tsarnaev hid from the police: “when investigators finally gained access to the boat, they discovered a jihadist screed scrawled on its walls.” The other was in Tsarnaev’s high school: “There are at least 50 nationalities represented at the city’s one public high school, Cambridge Rindge and Latin School, whose motto—written on walls, murals and school-course catalogs, and proclaimed over the PA system—is ‘Opportunity, Diversity, Respect.’”

Neither inscription is a work of art, of course, and both were contained in a semiprivate domain. However, the cover of Rolling Stone—thought to depict a boy-giant terrorist in a gossamer haze—sparked such hysteria that the mayor of Boston publicly denounced it, several chain stores refused to carry it, and the editors resorted to prefacing the profile with a disclaimer. Soon after, a disgruntled 25-year veteran of the Massachusetts State Police released a tactical police photograph of Tsarnaev in defiance of the Rolling Stone cover, to “counter the message that it conveys” and to unveil “the real face of terrorism, not the handsome, confident young man shown on the magazine cover.” The police photo showed the young man’s face in the bulls-eye of a laser sniper, head lowered and bloodied hands raised. The sniper photo of Tsarnaev was presumably leaked in order to give comfort to his victims, not unlike the ideology that undergirds “Boston Strong,” the city’s adopted moniker after the blasts.

The original cover portrait of Tsarnaev is indeed telling, but not because it glamorizes or idealizes its subject. If anything, it has the neutrality of a self-portrait, a surface where deeply lodged wishes and fears materialize.