WHO could have predicted that the most potent image to emerge from July’s Democratic National Convention, with its hoarde of celebrity darlings from Demi Lovato to Chloë Moretz, would be that of an aging Pakistani couple who had lost their son to the Iraq War?

In a matter of six minutes, Khizr Khan and his wife Ghazala became ideal fetish objects for a certain class of liberal-centrists in the Democratic Party who believed that they had found in the Khans the perfect avatars for the campaign’s values—and, by extension, vessels for their imagined moral superiority to the Trump voter. He, a lawyer by training, spoke with stentorian force about his son’s death twelve years ago during the Iraq War. She, stood beside him, a placid totem of suffering. What a humiliating theater they had agreed to; it did not even take a minute for the audience to interrupt Khan with a roar of applause, followed by a rumble of onlookers chanting “USA! USA!”

Midway through his speech, Khan held up a pocket-sized dollar Constitution, as if offering the ultimate retort to the pungency of Trump’s ideologies. Trump, Khan explained, had sacrificed nothing.

America was not used to seeing faces like those of the Khans become celebrities. The Khans rocked them to their core, becoming the overnight sensations of the DNC. Within minutes of airing, the speech made the Google Trends for “register to vote” swell.

Watching images of the Khans go viral made me profoundly uncomfortable. I wasn’t, for one, used to seeing people who look and sound like my parents populate my feeds. The Khans had become brown celebrities unlike any the country had ever seen: they were nearing old age, they were heavily-accented, they had lost their son to a war he fought on behalf of the United States, they were Muslim, they were South Asian. How could one couple, and their invisible dead son, stand for so much?

They couldn't, of course. All their valences became conveniently flattened into a tale of feel-good patriotism. The worth of this non-white family was rooted in their proximity to militarism. What made them American was the fact that their son had fought and died for an ultimately useless American war.

The Clinton campaign had turned the Khans, two grieving parents, into items of political currency. At first I excused this, knowing that politicians must unfortunately use human lives as leverage for gain. But what’s upsetting, in retrospect, is how the Khans have now become part of the laundry list of ineffective bait. They didn’t kill Trump’s campaign.

What people so loved about the Khans—his oratory finesse, her stillness—Trump warped into evidence of moral bankruptcy. Ghazala Khan’s silence invited projection, and, where some used it to extrapolate symbolic meaning of her unspoken suffering, Trump asked: Why was a husband speaking for his wife? Didn’t her silence prove his point about the second-class citizenry of women in Islam?

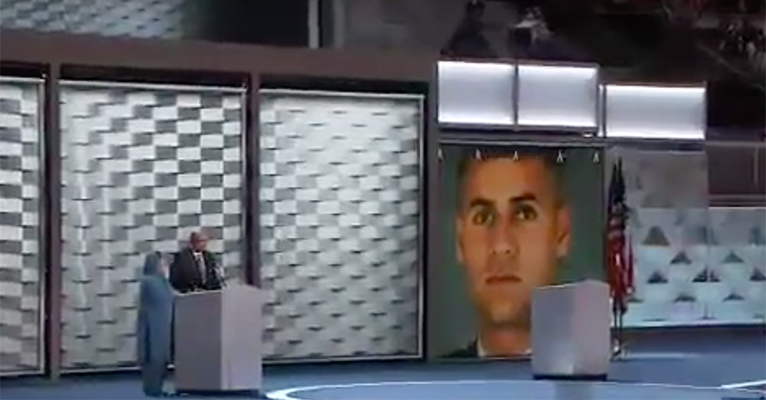

So vicious was Trump’s opprobrium that Ghazala offered a rejoinder in the Washington Post. “Trump criticized my silence,” the headline declared. “He knows nothing about true sacrifice.” It read like a ghost story. Ghazala still cannot walk into a room with her dead son’s pictures. She cannot clean his closet. She was speechless on stage, if we must know, because an enormous projection of her dead son bore down from the ceiling—a domestic horror on view for all of America to see.

Ghazala survived the Indo-Pakistani War while she was still in high school. This colored her understanding of war irreparably and made her reticent about her own son voluntarily going into a conflict. "You can sacrifice yourself, but you cannot take it that your kids will do this," she wrote. At the time, she begged and pleaded for him to stay.

Watching the video of Khan’s speech, one realizes that its comfort—and what allowed it to travel and be so widely disseminated and attract sanctimony—lies in its vagaries. Missing from it was the texture of the Khans’ backstory; one of the most evocative pieces of reporting is over a decade old. It had not even been a year since Humayun Khan’s death when, in February of 2005, Stephanie McCrummen of the Washington Post wrote a profile of Khizr Khan. McCrummen caught him in a moment when the wound of his son’s death was still gaping. The piece detailed how Khizr and his wife came to Silver Spring, Maryland in 1970 from Pakistan to seek refuge from the constant militaristic strife that the Partition of India had introduced in 1947.

Humayun was their middle child. Midway through his time at the University of Virginia, he declared that he would join the ROTC, all in service of joining the Army upon graduation in 2000. It would be his way of giving back to what ROTC had given him. He completed his four years of service before being deployed to Iraq at the beginning of 2004. In June of that year, four months after arriving, he was killed while trying to stop a suicide bomber. In dying, he earned a Bronze Star Medal and Purple Heart.

What brought the Khans into the purview of the Clinton campaign was a December 2015 profile of Khan, this time by the VC-funded website Vocativ. In it, Khan criticized Trump’s profound intolerance of Muslims. Clinton’s team then recorded a video just days later wherein Clinton called Captain Khan “the best of America.” The campaign then contacted the couple about speaking at the DNC, culminating in a denouement that seemed, for a time, that it would be sewn into history as one of the watershed moments we would use as a document to pinpoint when, exactly, Clinton clenched the presidency.

The Clinton campaign’s use of two parents to a dead military son was pretty rich stuff from a candidate who has played rather large hands in militaristic campaigns in Yemen and Honduras. In deploying the Khans as righteous responses to Trump, it was as if the Clinton campaign had deliberately tiptoed around one of the many sources of public distrust—the presumption that she was a war hawk. Her campaign did little to assuage any fears that she would, if President, wheel this country into a war like the one that killed Humayun Khan.

AS of late, there’s been a fascination with how far ahead Clinton is in the popular vote, operating in ignorance of the rather obvious fact that a truly savvy politician would have gamified their strategy to win the electoral vote that actually matters. Her campaign should have been a cakewalk; she was literally slumming against a reality television mogul. It is the responsibility of a candidate to stoke enthusiasm and to engineer it in pockets of the electorate where it doesn’t yet exist, and Clinton was woefully insufficient on that front. This failure is the Democratic Party’s cross to bear.

Clinton defined herself in opposition to Trump's antagonism rather than sending the electorate a dedicated, cogent message that she would not again vote to authorize the invasion into Iraq that killed this fallen Captain, whose parents she used as pawns. A war like this has done a lot to feed the same fear that bigots now have credence to act upon.

The Khans became collateral damage of the Clinton campaign’s mixed messaging, one that did not sufficiently address Clinton’s own culpability in nurturing the same military state that has increased suspicion against Muslim and brown lives. This is the pulse of an American electorate that Trump spoke to with crude efficiency. With his election, his promise to make the lives of innocent South Asian Muslims, like those of the Khans, materially worse is now a reality.

Last month the Khans recorded a video for the Clintons wherein Khizr recounts his son’s death. His voice trembles, and the camera lingers on him as he becomes visibly more fragile and wordless than he let himself be on stage. The video cuts away just before he begins to cry and instead pans to a photo of Clinton looking proud and defiant, the typeface below her claiming we are “Stronger Together.” The video’s cruel symmetry makes me sick: Humayun Khan risked his life for a lost cause, and now, his parents have done the same.