Rationalized identity construction and the postauthentic data self

In this paper, I want to trace changes in the ideological notion of personal authenticity that have been brought on by widespread social media use. Earlier notions of authenticity were premised on a unique interior self that consumerism would help us express, but social media have made that untenable. In response, authenticity is shifting, describing not fidelity to an inner truth about the self but fidelity to the self posited by the synthesis of data captured in social media — what I here call the data self. This sort of decentered authenticity posits a self entirely enmeshed in algorithmic controls, but it may also be the first step toward postauthenticity, in which identity ceases to be conceived as personal property.

“Becoming oneself” has turned into a crappy job — a compulsory low-paying, low-skill job. The promise of modernity, that we might escape the contingent circumstances of our birth and become who we “really are,” has become an injunction to continually work on the self with no hope of ever fully knowing ourselves or feeling fully recognized. Neoliberal ideology, as Jodi Dean argues in the quote above, effaces boundaries between work and life and requires subjects to continually seek opportunity to prove their creativity and flexibility. Social-media companies have emerged to offer just that, an endless number of opportunities for us to test our creativity and transform everyday life experience into proof of our economic fitness. Social-media profiles may thereby become necessary collateral, mandatory passports to participate in a consumer society gone “social.”

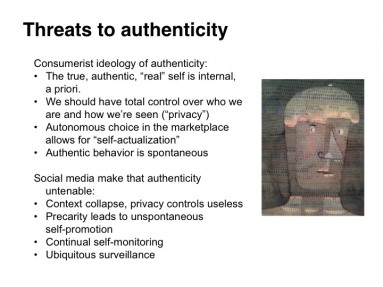

But being oneself was supposed to be joyous self-discovery, not work, not reputation management. Consumerism encouraged the idea that we were born unique individuals and that we could display that uniqueness to the world by buying things. This became the basis of the modern notion of authenticity, one of consumerism’s most successful and desirable products.

The demand for commodified authenticity is an expression of consumers’ nostalgia for a never-existing time when one had total control over the development of one’s identity. That sort of authenticity has always been a fiction, but the very real existence of goods that signify authenticity masked that fact. Consuming authentically could seem to prove fidelity to our “real self.”

Networked sociality threatens that notion. Though social media are sold as means of self-expression that let us articulate our real selves (with our real names!), they are also intrusive, invasive technologies that make surveillance ubiquitous. They dissolve the continuity of personal identity into discontinuous data that can be sold to marketers or recombined to create synthetic truths about us.

Social media are forums where we can test our uniqueness. While this can provide a sense of triumph (congratulations! 20 retweets!), it can also yield paranoia and a constant feeling of self-promoting phoniness as checking one’s reblogs, likes, messages, and comments becomes compulsive.

The calculating self-consciousness cannibalizes authenticity, contravenes spontaneous self-expression. Authenticity starts to merely measure the gap between who we’re trying to be and how we are actually seen rather than stand for some intrinsic essence. And given how social media can decontextualize these authenticity games, we can’t possibly know how large that gap is. It becomes conceivably infinite.

Authenticity as fidelity to an autonomous, unified a priori self becomes untenable. Social media inevitably confront us with our inconsistencies and our poses.

So how does the neoliberal self, in its perpetual state of selling out to maintain economic viability, survive its apparent inauthenticity? How do we regain a feeling of control?

If we maintain a belief in authenticity as fidelity to a static, preconstituted inner truth, we almost have to opt out of social media to salvage our integrity. That’s not an economically viable option, though, so the ideological construct of the “true self” must modulate.

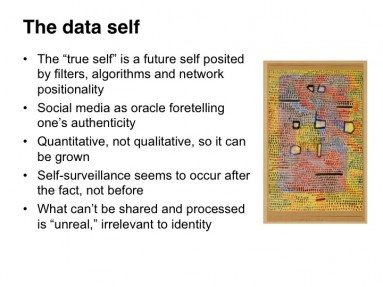

While we can still superficially subscribe to authenticity as an ideal, the exhortation to “be ourselves” has given way to the soft commands to always be measuring ourselves and sharing more information as a means to take that measure. Authenticity is no longer given and proved by unique consumption but established by the volume of one’s productive behavior in social media. We are only what we express and share; what escapes capture is not authentic but irrelevant.

The true self, from this point of view, doesn’t precede the process of being encoded in social media; instead the real self — real in the sense of being influential — emerges through information processing (sharing, being shared, being on a social graph, having recommendations automated, being processed by algorithms, and so on). As information is processed and assimilated to the archive of self, it begins feeding into the algorithmic systems that report back to us the true nature of who we are. (Think: the quantified self, or imagine Pandora, only played out across the entire spectrum of social life.)

So what is real about ourselves depends not some internal ability to think or feel something but the ability to externalize it as processable data. We surrender the prerogative of claiming to be self-created and learn to love the self the data tells us we are. We let Google or Amazon or Facebook tell us what to do next, and then we tweet about it or put it on Tumblr.

The move to a data-self basis for authenticity is a move away from qualitative identity a quantitative one, away from self-surveillance before the fact to self-surveillance after the fact. With the advent of the data self, the self’s basis of reality shifts from the past to the future, where the templates of social media hold the self in place and reveal it as it emerges, giving it coherent form through its searchability and availability to algorithmic processing and collective rating. We don’t even have to act on these recommendations for this self to anchor authenticity. The data self’s existence alone proves our potential. In its quantification, the data self offers a self that appears growable rather than fixed.

The data self no longer seeks meaning through action; it seeks to be processed into meanings. It’s available for audit and pliable to the incentive structures built into social-media platforms. By letting social media capture and process everything, a more reliable, socially authenticated version of the self is produced, better than what our memory can give. Facebook Timeline, for instance, can be seen as an infographic of our personality so compelling that we can comfortably overlook its formulaic nature. Facebook invites us to forget we even had a self before Timeline was there to organize it.

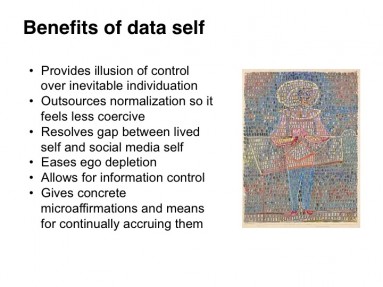

Why would anyone buy in to the data self? First, it fits better with the actual, continual process of individuation we are all always undergoing. No one is as self-contained as the ideology of individualism asserts. Social media seem to afford more control over this interdependent individuation process, making the burden of self-surveillance into a procedure of self-care.

Social media give us a dashboard for reputation management — the smart phone serves as the controller for the real self, while we outsource the finalization of our authentic identity to the machines that report it to us with certitude, filtering what we see and goading us to act along formulized lines. The platforms pre-certify certain courses of action as “authentic." We’re told how we should be under the guise that it’s already what we have been. The data self can be embraced as normative but not coercive. The coercion happens in the algorithms, not interiorly.

Whereas the old Freudian self aspired to normality but remained a unique product of its dysfunctions, the data self can achieve normality relative to a statistical average profile. Just as the “tastes and interests of people who don’t yet exist within systems can be easily predicted based on the patterns of others,” as danah boyd noted, so can our own future selves.

This makes it so we can’t fall short in expressing a true self, solving any need to be loved for “who we really are” by convincing us we are nobody until algorithms tell us how we were loved already. Social media also match us with those people who can best affirm us. The pleasant Pavolovian buzz of seeing someone respond to one of our social media posts is not merely pleasure at having gained some attention but a momentary reassertion of control over identity.

With all of social media’s feedback loops, we get a comprehensive status update from ourselves, allowing us to consume our own personality as novelty. We effectively set a Google alert for our soul.

The data self allows us to view the self as productive along neoliberalist lines, giving a protocol for handling both too much visibility and too much information. It gives us something practical to do with our experience. Social media instigate what Bernard Stiegler has called a “grammatization of the social”: giving standard forms by which everyday-life experience can be captured and processed to imbue it with legible meaning. It makes that experience “real” in the sense that augments our reputation in the data forms neoliberalism demands. It makes memories into curated cultural capital.

As we see that cultural capital build, we strive to document as much as we can within social media, thus mimicking at the personal, micro-level the macro-level aspirations of Facebook to assimilate all of sociality on its “social graph.” From this totalizing system, we can then derive the comfort that everything will be recorded and be factored in — we don’t need to decide in advance what is significant, what to consume or not consume. With social media as a personal content-management system, we get to consume more than ever, free of the supposed guilt that comes from consuming the wrong stuff or showing off.

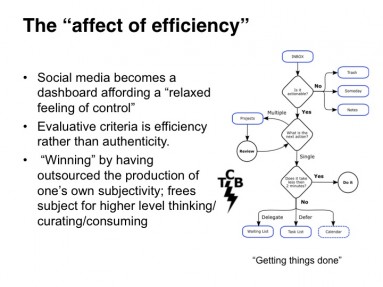

The system conveys what Adrian Mackenzie calls “an affect of efficiency,” which complements neoliberalism’s emphasis on self-directed productivity.

Social media’s sharing rituals and feedback loops give the subject momentum, a sense of control over both the flood of information in and the flood of information out. Their ability to capture everyday life becomes not a threatening form of total surveillance but a giant Getting Things Done flowchart for processing life experience. In this system the evaluative criterion of experience is not exposure or authenticity but efficiency. Can it be disposed of?

The flow of operating social media affords the same “relaxed feeling of control” that Mackenzie claims productivity manuals promise. This is the data self’s consolation prize. Outsourcing identity production and submitting to quantification also begets a feeling of superiority, of winning: As Melissa Gregg argues, “metrics allow the creator-God to be liberated from the fallibility of self and others.”

But in reality, the data self is hardly godlike. If anything, it more closely resembles Deleuze’s concept of the “dividual” — the encoded, premediated subjectivity of the society of control. The data self cannot exist apart from social media and is at the mercy of how they calibrate their filters. The data self may not face the threat of inauthenticity but it’s intensely threatened by the possibility of being disconnected, of having the information flow disrupted. That reflects an underlying terror that there’s something crucial about our lives that can’t actually be expressed — integral things that can’t be processed.

But what the data self may ultimately offer is a bridge to precisely that kind of contentless identity, an identity that doesn’t signify. Rather than being hopelessly trapped in authenticity games, the data self, as an outsourcing of identity, could point toward postauthenticity, in which the momentum of sharing itself is all that needs to be shared, and identity becomes noninterpretable.

The attachment to the unique individual self has been destructive in its defensiveness. That self perceived threats everywhere to the originality that seemed to be the basis of its value. The data self dispenses with originality but retains the need to create value through producing identity and managing reputation. The next move could be to decouple subjectivity from cultural capital and identity, and embrace the idea of identity as ephemeral, with no need of reputation management to qualify for pleasure in the networked society.