The story of focus groups is often popularly imagined as a story of failures. They’ve made our movies boring and our politicians cowardly. They made New Coke. The people who pay for focus groups—the corporate executives and the creatives and the politicians—also hate them for their limited vision of the world. How can one innovate under such conditions, having to listen to people who don’t know what they want? They shouldn’t be trusted. Malcolm Gladwell says so, and he’s a staff writer for the New Yorker. He’s got best-selling books. He wouldn’t have given us New Coke.

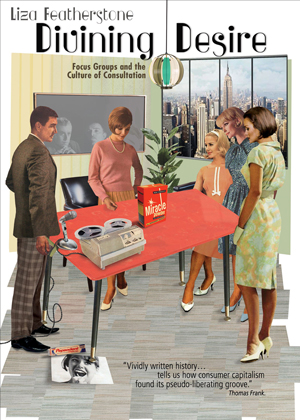

Liza Featherstone, Divining Desire: Focus Groups and the Culture of Consultation. O/R books, 2017. 304 pages.

That story is not the one Liza Featherstone, a columnist for the Nation, activist, and author, tells in Divining Desire: Focus Groups and the Culture of Consultation. Instead, she tells “a story of elite degeneration” that starts with the birth of the focus group, which served no less noble purpose than to defend democracy itself. Or that’s, at least, what the men in charge in the early 20th century would have liked to believe.

In the lead-up to the U.S.’s entrance into World War II, the Office of War Information contracted the Bureau of Applied Social Research at Columbia University, helmed by sociologists and left-leaning democratic socialists like Robert K. Merton and Paul F. Lazarsfeld, to “test propaganda.” The New Deal liberals and social democrats who devised the strategies were seeking “the masses’ consent for bold, ambitious plans” like going to war with Nazi Germany. From there, Featherstone shows, the mechanism of the focus group was born, not to simply record public opinion but to help control it.

In Featherstone’s description, this move stemmed from a deep belief among these elites that the people only needed information framed in the proper way and they would understand that the elites had been right about everything all along. “Leaders were beginning to grasp the gap between themselves and the masses,” Featherstone writes, “yet those same elites had a great faith in the power of persuasion. They knew the people did not always agree with them, but were confident they could be convinced.” The role of the civilian was not to help the government figure out what plan would be inherently popular among the people because it would address their needs but to submit to whatever plan the government had already devised and make it become popular.

The line between persuasion and coercion is blurry, particularly when the force of the state is involved. The New Deal liberals wanted to convince the populace, not manipulate them, but this did not mean their goal was fashioning a more democratic governance. The focus-group techniques of listening and reporting that the academics devised proved effective in prompting citizens to maintain wartime productivity and purchase war bonds. After the war, with their effectiveness now established, these techniques made their way into the advertising industry, whose patronage helped keep the Bureau of Applied Social Research afloat.

Just as in the earlier, more explicitly political use of the Bureau’s focus-group approach, the advertising uses purported to record mass opinion while actually shaping the role of the consumer. In the postwar years, focus groups played an important role not in clarifying what consumers’ desires were but in helping create the political identity of “consumer,” which was held to be necessary to combat what politicians and executives saw as that figure’s opposite: the communist.

In Featherstone’s view, this approach proved to be self-defeating. As focus groups gained prevalence, their very effectiveness seemed to undermine the ideal of consumer autonomy that they were meant to shore up. Sociologists began to be concerned about conformity and other group-oriented behavior, a worry typified by books like David Riesman’s The Lonely Crowd (1950). The anti-communistic function that the role of consumer actually served benefitted a capitalist oligarchy.

The structure of that power dynamic is important to keep in mind when considering high-profile stories about focus groups’ failures, which always involve the powerful shunting blame to the amorphous masses. For example, when the Ford Edsel flopped in 1957, critics claimed that the company had, in Featherstone’s words, “listened too long to the motivation-research people.” The story was then adopted into the pantheon of marketing clichés as proof that listening to focus groups produces inferior products. As one CEO that Featherstone quotes says, “You can’t use focus groups to create an idea . . . a focus group would create an Edsel.”

But as Featherstone shows, this distorts what happened with the Edsel. The name was tested with a group, but they rejected it because it “sounded too much like ‘weasel.’ Executives went with it anyway.” The design of the car, which was widely hated, was produced without consulting focus-group research. This story about the stupidity of the people and warmhearted elites who trusted too much, then, is actually a story about arrogant executives who wasted money on focus groups that they decided to ignore.

The same is true with New Coke, another of anti-focus-groupers’ go-to examples. As Featherstone argues, “The New Coke disaster can more accurately be blamed on the company’s failure to listen to its focus groups, which in fact revealed deep attachment to the Coke brand . . . That’s because focus groups can mirror the group effects that are an important part of the real marketplace. The groups revealed profound opposition to changing Coke, and the ways in which consumers could affect each other’s opinions about such a change.”

Both of these anecdotes reveal not only the bad faith with which the elites engage with the masses when they’re willing to engage at all but how elite skepticism of focus groups can be a self-fulfilling prophecy. Featherstone establishes that what focus groups demonstrate is not the desires of a group of individual autonomous consumers but the way individuals’ desires are shaped by social groups. No consumer (or person) exists in a vacuum; focus groups point to the sociological, political, and economic value in understanding how groups have an impact on people’s actions. Featherstone sees the production of that knowledge, even when it is put to banal corporate ends, as vital.

Featherstone’s book is a fascinating history, but at times it sidelines its concerns with power structures in order to champion focus groups’ progressive potential when not being betrayed by capitalist elites. Her framing occasionally draws on capitalist criteria to establish the way focus groups are misused: It’s clear that executives arrogantly ignored focus groups because their product initiatives failed—profit is held to prove the wisdom of the people, and executives ignore it against their better interests. But when focus groups are convened by politicians and not corporations, it’s not clear by which criteria one should evaluate whether focus groups are being misused or unduly ignored.

“Ordinary people are listened to more than ever, even as they have less and less real power,” Featherstone writes, using as evidence the “Walmart Moms” focus group in 2011, which recruited mothers of children under the age of 18 who had shopped at Walmart in the last month and was conducted in Orlando, Florida; Manchester, New Hampshire; and Des Moines, Iowa. “Only in this sort of political environment could a company notorious for rendering working-class women powerless and exploited then turn around and theatrically display their voices, one in which elites ignore the actual needs of the masses, in this company’s case for living wages, healthcare, and equal treatment.” This example of insincere corporate listening and “caring” is obviously not geared toward any real change: Walmart could improve the lives of a lot of working class people any time they wanted to, and it is indeed absurd that they would put on a Potemkin focus group like this anyway. Still, Featherstone’s choice to focus mainly on that dynamic instead of what the moms in the focus group actually said is telling. She shares that their primary concern is jobs and, by proxy, money but also that they wish Congress would “bicker less and compromise more” and that they “blame themselves and other ordinary Americans like themselves . . . for living beyond their means.” These suggest that the political vision of the masses, or these masses anyway, might not align with a left policy agenda.

Featherstone’s broad diagnoses about the ailments corroding American society are spot on, but her story about the masses and the elites sometimes fails to take into account how the masses actually feel about what’s going on. She tells a compelling story about the ever widening space between politicians seeking high office and the voters who elect them, which created an ever growing need for focus groups, but there’s no accounting of what the masses actually want or the ways they’d held power in the past.

Featherstone points to the disturbing “degeneration” of democracy over the lifespan of the focus group, identifying a delicate dynamic wherein, as inequality grows, elites and the masses become more distant, increasing the need for focus-group-style mediation to allow the masses to feel more “heard,” even as their real power declines—assuming they’d had it in the first place. But this misses the ways in which established power in America from the very beginning of the nation has always worked to constrain democracy. The Constitution’s compromises—slavery, the structure of the legislative bodies, the Electoral College, and others—made the nation possible but also institutionalized systemic inequity. Featherstone correlates the decline in popular power with the rise of the focus group, which began “its ascendance in the mid-1970s,” and that structure is tough to swallow when the Voting Rights Act had only been law since 1965.

A broader interrogation of exactly how democratic the United States of America has ever been would have helped attenuate Featherstone’s examinations of how far its been degraded. Still, she’s clear on how that problem manifests as it relates to the culture of consultation: “This is what we should be mad about: that our democratic institutions can’t be trusted to represent our interests. When a focus group feels more like democracy than the real thing, we need to ask how well the real thing is functioning.”

The book’s final line suggests that these problems can be ameliorated with “organizing, persuading, and challenging.” This is not a bad idea. In fact, it’s a necessary one. It’s also one without a clear goal. It seems to rely on the questionable assumptions that the “masses” are already a unified group that shares enough interests and are just waiting to have the opportunity to speak their truth to the elites.

Featherstone is not alone in hitting this wall. Brooke Gladstone, host of WNYC’s On The Media, reached a similar impasse in her book The Trouble With Reality, released earlier this year. Gladstone focuses on an intractable problem that Featherstone tacitly acknowledges toward the end of her book: It is not just the masses and the elites who are living in different worlds. The masses themselves are fractured into groups with entirely distinct realities, and though this is largely a result of narratives put forward by elites who command large audiences through their control of or access to mass-media channels, it has entirely pervaded society, especially on social media platforms.

In Divining Desire, Featherstone mentions the disturbing phenomenon of watching a member of a televised focus group of undecided voters state with certainty that Barack Obama was a Muslim and seeing the rest of the participants nod in quiet agreement. But she doesn’t point this out to vilify focus groups but to cast herself as the villain, writing that “the hostility to focus groups is a populism of fools—which really looks more like elitism.”

That may be true, but Featherstone’s readiness to defend the practice and its participants misses the more significant problem, which Gladstone identifies, that these views and the certainty with which millions of people hold them in the face of factual evidence is a world-historic issue that has already had catastrophic consequences. Featherstone doesn’t engage with a fractured populace in her conclusion. She writes, “conversation is critical to movements but conversation without clear thought about building institutions and power can be dead end.” She’s right, but this claim rests on the assumption that the “masses” of the United States of America are already close to agreeing about what type of institutions they’d like to build or what type of power they’d like to have. If only that were true.