A review of Out of the Vinyl Deeps by Ellen Willis

Ellen Willis writes, in the opening line of her 1969 article on The Rolling Stones, “The Big Ones,”: “It’s my theory that rock and roll happens between fans and stars, rather than between listeners and musicians—that you have to be a screaming teenager, at least in your heart, to know what’s going on.” This may be the single best description of rock criticism I’ve ever read. To write on this music masterfully, you have to be a screaming teenager—at least in your heart. You have to surrender the critic’s cool detachment and throw your bra at Mick Jagger while yelling his name. Criticism of rock and roll, the musical form most invested in the idea of cool, is itself profoundly uncool.

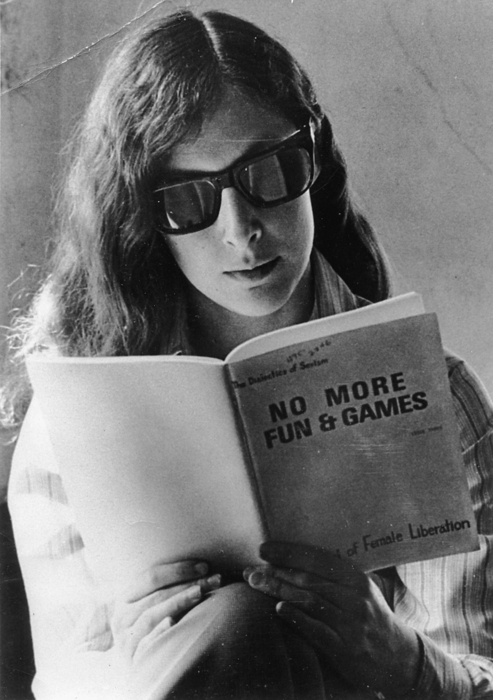

Ellen Willis, however, may actually have been cool. The same essay continues: “I was never much of a screamer.” She explains that when attending Elvis shows as a teenage girl, she would scream, but only “so as not to be conspicuous.” But being a rock fan is all about being conspicuous, and being conspicuous is exactly what makes all rock fans uncool. Until now I had thought of rock writers, especially those from Willis’ era, as the screaming fan in the middle of the silent crowd, the loser who loves the Rolling Stones so much that he doesn’t care if everyone else in the room stares at him and thinks he’s a loser. In fact, maybe he hopes they stare. Maybe that’s why he’s writing about rock and roll.

Out of the Vinyl Deeps: Ellen Willis on Rock Music, edited by Nona Willis Aronowitz and released by University of Minnesota Press, is the first full anthology of Willis’ writings on rock music. The book collects her work both as the first popular music critic for The New Yorker, and in numerous other publications from the early sixties through 2000. In the most obvious way, this anthology is important because Willis has until now escaped proper canonization and compilation. As critic Scott McLemee, in his Inside Higher Education column on Out of The Vinyl Deeps, writes, Willis’ writing is thematically and temporally of a piece with “those rock writers of gigantic stature — Lester Bangs, Robert Christgau, Nick Kent, Greil Marcus, Dave Marsh, Richard Meltzer, and Nick Tosches — [who] thundered across the countercultural landscape, sometimes doing battle, like dinosaurs. (Big, stoned dinosaurs.)” That Willis come into the same prominence as her male colleagues is necessary; that this has not occurred until now is shameful. As has been stated elsewhere, her appearance as a female writer in a male-dominated field almost certainly explains this oversight.

But what is meaningful about Out of the Vinyl Deeps, an anthology whose importance to the genre and sheer virtuosity cannot be overstated, is as much where it breaks from the existing genre of golden-era rock criticism as where it performs dizzying feats of fandom-as-criticism (or criticism-as-fandom) along with the best. It does the things Willis colleagues’ did, but also fills in an existing lack in rock writing. And that addition is intrinsically connected to the fact that Willis, unlike any of her contemporaries, actually seems to have been cool.

Admittedly, I became a fan of Willis only a few years ago, and only after discovering known rock writers from her era. My love affair, not only with rock criticism but with rock itself, began when I read one of Willis’ contemporaneous critics. I came to rock and roll entirely backward, through the sheer, propelling force of Lester Bangs’ critical howl. Bangs is the ultimate fan-as-critic; his criticism is the most perfected form of fanboyism, and in it he basically, if not literally, elevates uncool to the level of poetry. I read Willis, therefore, as I read all rock-criticism: against Bangs’ example. As it turns out, the two could not be more polarized: they take opposite tacks in order to do the same thing. This very sort of irony, this living, productive impossibility, synonymous antonyms, is both the defining theme of Willis’ writing on music, and the quality by which she defines rock and roll. It is also, not incidentally, the very problem of cool.

Out of the Vinyl Deeps does not proceed chronologically but rather is broken into thematic sections, named for different roles that Willis plays as a critic: “The Sixties Child,” “The Adoring Fan,” “The Feminist” and so on. Each of these sections then proceeds chronologically through her essays. The sections repeat the same story again and again, each time through a different filter, focusing on a different theme: the story of Willis’ changing relationship to the music she loves, and the story of a certain strain of popular American culture. The book follows rock music from its emergence in the late ’50s through its repeated rebellions and counter-rebellions. Within each section the same problems are highlighted, the same obsessions emerge. Even as the collection speaks in Willis’ single voice, it takes on a choral plurality, a single musical line repeated from different angles, refracted through new arrangements. In some ways the collection feels like an all-night conversation, as each new topic circles back to the same concerns and opinions, seen through new anecdotal evidences and possibilities.

In her essay on the Velvet Underground, published in Greil Marcus’ “Stranded,” Willis references “the spiritual paradox: to experience grace is to be conscious of it; to be conscious of it is to lose it.” This is, of course, the same paradox that makes cool impossible: The minute one wants to be cool, one is uncool. Cool, in its ideal figuration, is a state of desirelessness. Cool defines rock and roll, despite the fact that rock and roll is itself all about desire, and thus, deeply uncool. To experience rock you have to be a fan, and to be a fan means wanting something very, very badly. It is, logically, impossible to be cool.

Willis locates the Velvets’ genius in exactly this contradiction. “Their irony functions as a metaphor for the spiritual paradox,” she writes, quoting the final lyrics of Reed’s eleven-minute masterpiece “Street Hassle,”: “That’s just a lie, that’s why she tells her friends. ‘Cause the real song—the real song she won’t even admit to herself.” The Velvets sing not the “real song,” but the “lie she tells her friends.” This lyrical irony demonstrates the lie and then the real song twitching to get free beneath it. The Velvets sing songs about deep, complex experiences in flat, detached voices. On “I’m Set Free,” Reed goes from the spiritual grace of “I just want to tell you everything is all right!” to the supreme callousness of “There are problems in these times/but ooh, none of them are mine!” with barely a breath in between. Willis describes the famous track “Heroin,” as “a magnificently heartfelt song about how he doesn’t care.” This kind of “paradox,” this co-habitation of opposites and forced resolution of irresolvable things, is the theme to which Willis returns again and again.

Willis’ female-ness within this group of writers functions with the same kind of irony. In an essay on Janis Joplin, Willis defines “singing as fucking” as “a first principle of rock ‘n’ roll.” The male writers who came to dominate the golden era of rock criticism took that equation one tributary, longing step further: Writing as singing as fucking; writing as rock ‘n’ roll. Willis’ prose, though gorgeous, lacks entirely the manic sexual energy of Bangs or Marcus. Its stunning clarity results from this difference. Willis doesn’t write as an act of rock and roll. Her prose is not an answer to the fact that she doesn’t have a band.

If this makes for beautiful criticism, it also forces a crucial question. Rock music is a male-dominated genre. The more feminism becomes Willis’ primary concern, the more she has problems with the fact, which she is anxious to articulate herself, that this is music by boys, for boys. Women are the point, but they are not included. Its love songs are manipulative, its hate songs cathartic, and both are at women, not for them.

In a 1974 review of a womens’ music festival, Willis says “I didn’t miss Fanny [a group who canceled at the last minute], I did miss rock ‘n’ roll.” The implicit concern is that rock is by definition masculine, and to have a womens’ festival is to have a festival without rock and roll. “Rock and roll is,” she continues, “among other things, a potent means of expressing the active emotions—anger, aggression, lust, the joy of physical exertion—that feed all freedom movements, and it is no accident that that women musicians have been denied access to this power.”

Male fans looked at the Rolling Stones and wanted to be them. There was no real barrier between a male fan’s place in the audience and his idols’ place on the stage. If only he could do something—that unnameable but entirely accessible, just-beyond-the-fingertips something—he would become Mick Jagger. Rock, as a genre that has always defined itself by apparent, if not actual, amateurism, is deceptively welcoming. Lester Bangs comes off as that asshole at the party standing around waiting for a girl to ask if he’s in a band. Willis, however, starts not with identification, but with distance. Her detachment allows her to articulate where rock music’s worth is simultaneous with its difficulties, to define it in its contradictions.

Vinyl Deeps is, as stated in Daphne Carr’s wonderful, moving blog post, “Inheriting Ellen,” important as an inspiration to young women. However, its effect and use is much larger. Out of the Vinyl Deeps is a perfect cultural artifact. The essays not written in the 1960s and 1970s discuss the memory of ’60s and ’70s, the fact, problem, and myth of them. But the past about which Willis writes and of which she is a piece is the legacy that created the present. Today’s struggles, including the question of why the hell something as trivial as rock music should even matter, are the same struggles Willis confronted and documented.

Rock ‘n’ roll matters because it is the story of growing up. Arguably, rock ‘n’ roll is the reason American culture contains the myth of adolescence. In the fifties this allegory was acted out almost literally as rock’s emergence crucially split adolescents from their parents. Loving something your parents couldn’t understand was the first way to leave home. Because rock and roll is the story of growing up, it is necessarily defined by rebellion, and is therefore required over and over again to locate something against which to rebel. In the same way, sex continues to be the material of rock and roll because sex is the figurative act by which we leave our parents’ home.

Rock music remains problematic because it is a form whose material is rebellion, practiced by and marketed to almost exclusively privileged consumers. “As a white exploitation of black music,” Willis writes, “rock ‘n’ roll has always had its built-in ironies, and as the music went further from its origins, the ironies got more acute.” As Willis points, out rock and roll, signified over and over as the music of the working class, is essentially bourgeois. A luxury that feels rugged, a privilege that tells stories about deprivation: these contradictions are the defining characteristic of rock ‘n’ roll, and the successes or failures of its artists is their ability to live within these contradictions.

Willis’ ultimate thesis is contained in the lyric she quotes in her near-unbearably elegiac final piece for Janis Joplin: “Don’t turn your back on love.” Her theme, finally, is vulnerability. This theme is not the simplistic “all you need is love” prattle of the Beatles’ early work. It is rather the aching empty-handedness in Lou Reeds inconclusive conclusion, “and I guess that I just don’t know.” Vulnerability is hard won, awful, and only meaningfully located within breathing contradictions. Our own most vulnerable interactions exist always in the same kind of painful state, where irresolvable things cling together in a desperate attempt to cohere. Irony expresses not cool, but rather its opposite. “The essence of grace,” writes Willis, “is the comprehension that our sophistication is a sham.” From her own seeming cool, Willis exposes human longing, and not its sentimental performance, as the heart of rock music. Numerous fans and critics go to rock’s poses hoping to escape their vulnerability; the greatest musicians and bands make music about that attempt at escape. At its best, rock music offers that unguarded humanity in a pure and celebratory form, and we should, as Janis tells us, get it while we can.