Just when you thought the world was a horrible, boring place full of assholes, Werner Herzog makes a movie in 3D. And not only that: it’s a 3D documentary about cave paintings. The film, Cave of Forgotten Dreams, is about the paintings in the Chauvet- Pont-d’Arc Cave in Ardèche, France, which, at 32,000 years old, are the oldest known paintings in the world. Forgotten Dreams succeeds—to a fault—in delivering all that we expect from a Herzog film: breathtaking images, eccentric locals, deceptive ethnography, grandiloquent voice-over, slipshod metaphysics, and a ridiculous New Age score, all executed with Herzog’s usual mixture of audacity and laziness. Though it is neither a superior entry in Herzog’s catalogue, nor the inaugural film to an era of artistically worthy 3D cinema, Forgotten Dreams is chock full of shot-from-the-hip sublime.

Herzog scored access to the cave, otherwise kept inaccessible to all but a handful of research scientists, thanks to the personal intervention of the French Minister of Culture, Frederic Mitterand. Herzog and a crew of three had a total of twenty-five hours to shoot in the caves, using only hand-held lights and custom-made, portable 3D cameras. Researchers interviewed provide just enough scientific context for the images to whet curiosity, and along the way we encounter the kind of tender, malformed personalities Herzog has made a career of conscripting into his mad visions—a circus performer-turned-archaeologist, an “experimental archaeologist” costumed in Paleolithic garb, and a master perfumer who sniffs out caves with only his nose. At the heart of the film, like at the heart of every Herzog film, is a Mexican showdown between Herzog, his subject, and Being itself.

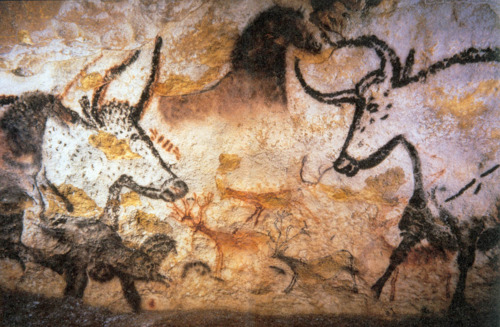

The paintings of the Chauvet Cave are things of astonishing beauty and sophistication. The figures are drawn in long, elegant lines and colored in with blended fields of ruddy pigment. Several animals drawn with multiple, blurred limbs convey a powerful impression of movement, an illusion that would have been compounded by the flickering of torchlight to create, in Herzog’s interpretation, a kind of “proto-cinema.” Thanks to a landslide that sealed off the cave 20,000 years ago, the lines are so crisp and the colors so fresh that, even from the safe distance of the movie theater, we share Herzog’s uncanny feeling that we have interrupted the primitive artists in their work.

Those savage sophisticates are Herzog’s ideal sparring partner. What interests Herzog is the physics part of metaphysics: transcendence, yes, but through action rather than thought, through a practical relation to the primordial substance via scientific experiments, feats of endurance, artisanal labor, and ecstatic visions. His films are populated by athletes, scientists, tradesmen, magicians, madmen, and prophets, but never by intellectuals or artists. Combining all of these roles in their most primitive forms, the Chauvet artisans are the ur-protagonists of every Herzog film. Former research director Jean Clottes speculates that the imagination of the Chauvet artisans may have been governed by two principles foreign to the contemporary mind, although not to Herzog’s cosmology: fluidity—which describes the blurring of ontological boundaries between the animal, vegetable, and mineral—and permeability— which describes the saturation of the material world with an immaterial potency that can be interacted with by material means. Perhaps, in the minds of their creators, the paintings had some power to directly communicate or intervene in the spirit world. For certain, the paintings are, like Herzog’s films, imagistic interfaces through which we commune with and differentiate ourselves from both the natural world and ourselves as a species.

Much is made of the fact that the paintings are among the earliest examples of figurative art—archaeologists privilege the emergence of figuration as a milestone in the development of human cognition. Yet one of the most evocative paintings is decorative, even abstract: a field of red hand-prints made by a single artisan. Considered alone, each handprint indicates the absence of a being with whom we cannot help but identify. Together, the panel of prints conveys pure, abstract intention—the primordial aesthetic impulse to make the things around us more interesting. Something like immortality lies in such abstraction. We may know that handprints are inert, that the hand that made them has long since decomposed, and that we, who apprehend them, are but electrified meat, but they nonetheless engender the illusion of a soul, an illusion which is itself all the transcendence we can ever ask for. If Herzog strives too hard to spell this all out, perhaps it is because, in the pre-historic artisans of the Chauvet cave, he has finally met his match.

Facilitating our appreciation of how the Chauvet artisans used the irregular surfaces of the cave walls to give their paintings a dynamic potency is the most valuable achievement of 3D cinema to date. The artisans used curves in the wall to emphasize the power of the animals’ bodies; ridges are exploited to give actual three-dimensional existence to their shoulders, spines, haunches, and horns. Some of the figures seem to chase each other in and out of crevices and along the slopes of the walls, while others seem to hide themselves away in protective niches. The most populated panels appear as spatialized swarms of spirit-beasts inscribed on intersecting, bending planes. Butterflies drawn on stalactites suggest that these immaterial creatures are not confined to the walls, but also stalk the cave’s vast emptiness.

Yet for all the 3D does to enhance our appreciation of the paintings’ physical properties, the primary effect of the technology is to make the paintings seem less material and more ethereal. This is the crux of the entire film, occurring in part by accident and in part by design, and its consequences are deeply ambivalent. A subtle convexity of the 3D image imposes an unnatural geometry on the images and makes them roil like smoke. The actual dimensions of the paintings, save for one, are never discussed. Their scale is never clearly established visually, in part due to a strong telephoto effect created by the 3D camera that obliterates our ability to discern the actual measurements corresponding to the film’s illusory depths, and in part due to no-doubt deliberate editing decisions. Bereft of any certainty as to their actual size, we simply accept the cave images as they appear to us in their cinematic enormity. They lose their objecthood and become pure image-ideas. The French philosopher Alain Badiou wrote that, looking at the Chauvet paintings, we see not horses and lions but horse-ness and lion-ness. That is certainly the effect of the paintings as seen through Herzog’s film.

For any true lover of art history, this is a serious loss. It is the worst sort of New Age pornography: faux-primitivism obscures the hyperreal relativization of History. Herzog’s use of 3D in Forgotten Dreams is the formalistic culmination of a career-long insistence on decontextualizing images to unlock their “ecstatic truth.” At their best, his films provide simple images of awesome and beautiful things that really do exist, while reminding you that you can not simply trust your eyes or the interpretations you ascribe to what you see. At their worst, they are elaborate mourning rituals for the reality they might have indexed. If Forgotten Dreams proves to be not only the first time anyone was allowed to film the Chauvet Cave paintings, but also the last, will we regard it as the most responsible use of that opportunity?

The efficacy of the preceding criticism is limited by the fact that there is no such thing, not even in the society of spectacle, as a pure image. Images are always accompanied by their contexts, interpretations, and uses. If we cannot hope to ever understand what the Chauvet Cave paintings meant to their creators, then perhaps their very inscrutability can at least awake in us the same feeling of wonder they evoked in the ancients. In the climactic reveries of Forgotten Dreams, Herzog attempts to restore to the paintings at least one of their original use-values: as tools viscerally inducing splendor and awe. The achingly beautiful play of Herzog’s handheld lights over the curves of the cave wall evokes, however distantly, the flickering of torchlight. In lieu of the crackle of wood, we have Ernst Reisejer’s score which, though marred by every terrible convention of contemporary choral writing (neo-Baroque melodies on top of African-sounding gibberish signify sophisticated primitivism), at least succeeds in allowing you to suspend higher cognitive functioning and settle back into trance. At one point, Herzog informs us that a certain panel contains overlapping images painted 5,000 years apart. “We are locked in History,” he says, “and they [the ancients] were not.” Whether the results constitute mere postmodern simulation or the genuine article, Herzog succeeds in breaking us out of History and inducing us to apprehend the paintings according to their untimely temporality.

It is hard to imagine a subject matter more suited to 3D treatment, but to conclude that the painting-contemplating sequences exhaust the potential of 3D filmmaking would reveal a poverty of vision. Even as Herzog takes the technique of simulation to its ambiguous triumph, he toys with more creative possibilities for the medium. Sometimes this involves the apotheosis of the banal in images more surreal than hypperreal: rain drizzling on a car windshield captures our attention just as much as the cave paintings, human bodies become strangely fragmented by their presentation in discrete planes of illusory depth, and saintly, three-dimensional nimbi appear embossed around human silhouettes, artifacts of the brain’s attempt to ignore the non-overlapping sections of stereographic image.

Elsewhere the sense of reality, lost at the level of content, is restored at the level of the means of representation—in the glitchy materiality of the 3D filmmaking process. When objects come too close to Herzog’s two-lensed camera, our ability to integrate the stereoscopic image into the illusion of a three-dimensional whole collapses. Herzog shrewdly deploys this technological defect in the last shot of his expedition to the caves. The camera, attached to a remote-controlled helicopter, slowly glides over the Ardèche River into the open arms of a crewmember. As the camera-copter nears its destination, the serene landscape begins to tear apart and the crewmember’s two outstretched hands divide into four. Our dilated pupils roll in our heads as we attempt to re-integrate the rapidly exploding image. It is physically painful to endure. At the moment of the camera’s arrival, the image becomes incomprehensible and cuts to black. It is an allegory of failure that retroactively colors the entire film.

A playful coda softens the blow of our brutal return to the contemporary world. Nearby to the Chauvet Cave is the Cruas Nuclear Power Station, where heated water from the plant’s cooling systems sustains an artificial tropical biome: a greenhouse populated by imported crocodiles. “Naturally,” says Herzog, “mutant albino crocodiles breed in these waters.” The implication, which both Herzog and the audience know to be false, is that the nuclear-heated waters irradiated the crocodiles, causing the mutation. The non-ecstatic truth is that albinism occurs with a higher frequency in all captive animal populations, as captivity reduces selective pressures against the mutation. The prevalence of albinism in the greenhouse is therefore “natural” enough in terms of the second-nature of this simulation environment.

Herzog has played an elegant prank on whoever runs the greenhouse, a facility no doubt established as a public relations stunt for the power plant. This is no primordial swamp, but the grim future: a post-human world dying of human-induced heat death. What, Herzog asks, will the crocodiles make of the paintings at Chauvet Cave once their swamp encompasses the world? Have we understood any more than they will? These questions seem silly, but behind them is a sinister implication: the way we are heading, there could be no one left to appreciate our oldest and most beautiful works of art except for this doomed race of freakish creatures, themselves our final, most terrible creations.