A Dangerous Method taps the allure of sexual dysfunction

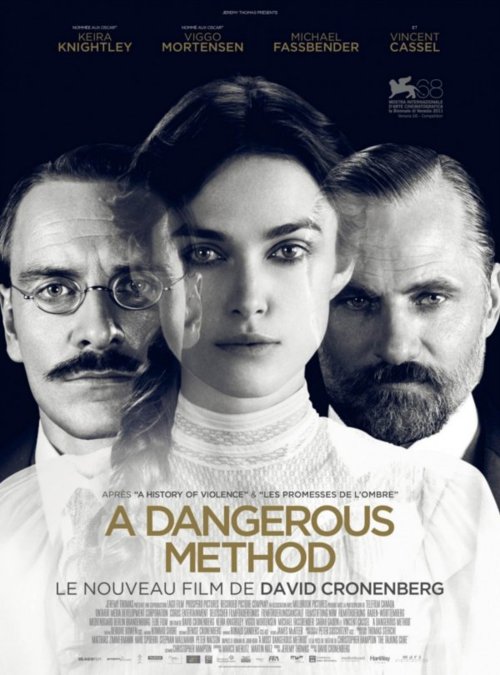

David Cronenberg’s new film A Dangerous Method opens with the ominous notes of a cello, that, leading out of the opening credits, give way to a horn and string crescendo and the disturbing first scene: Sabina Spielrein (Keira Knightley) arrives screaming, restrained by men, in a black carriage drawn by black horses, at the Burgholzli Clinic. And as our stomachs vibrate from the bass and the violence of the scene just past, a calm Carl Jung (Michael Fassbender) greets his new patient in a beige paneled room with dark parquet floors and bounced light. This is Zurich. It is 1904. Sabina suffers from mental hysteria (with spontaneous orgasms provoked by humiliation), and she and Jung eventually begin a sexual relationship.

In these early meetings between Jung and Spielrein, conversation occurs in total silence — that is, without any background atmospheric noise. No cricket or ticking clock gives the stillness form. This is a pure and unnerving silence. Chirping birds add texture to the air, without which the infinity of time and space weighs down upon you so that it is unthinkable to sleep without the whir of a fan. Hyperconsciousness promotes a focus of such stimulating intensity, it quickly becomes erotic, and at the end of the long road of observations that occur in the first moments of a movie, you find yourself contemplating the details of faces and bodies with growing arousal.

You realize that there are three lines decorating the expanse of Fassbender’s forehead. And as you admire the precision of those lines and the glorious precision of his upper body, the precise subtleties of his performance and how each tooth in his head lies precisely against the next tooth, you think increasingly of Keira Knightley and her humiliation upon first unveiling her character on set, not because her performance was weak (it was strong), but because, rather strangely, it is all about her vagina.

Not as glistening pussy, but vagina ungroomed, as anatomical fact.

I’ve never wondered about Knightley’s vagina before. Her characters, though romantic leads, seem vagina-less, and yet watching A Dangerous Method, I was very aware of it. To be quite honest, I was concerned with its scent, which, according to my imagination, is distinct but not unpleasant.

That the scent of Knightley’s vagina would come to mind isn’t completely absurd. In the film, Sabina’s vagina acts of its own accord. Muscles clench, unclench, and clench again despite the wishes of their owner. Neck shortened and shoulders tense and bowed, Sabina exists in anticipation of these orgasms. Like a hero lying on grenade, ready to absorb the impact of the impending explosion.

The vagina is the problem, the great burden. It can’t be controlled. And this is why it is a vagina and not a pussy. This is a raw and unsettling sexuality, raw because it isn’t controlled by intellect. And because it is raw, it is primal, and because it is primal, it is animalistic, it is dirty, and by dirty I mean not sanitized, and because it is not sanitized it has a scent, as all adult vaginas do. Any woman knows that the scent she now produces differs from the one that wafted up on the day she discovered how to masturbate. An adult vagina is a different thing with a different skill set. An adult vagina may be immorally moved to an inconvenient climax, and as heat and moisture build (inside Victorian pantaloons), a gentle scent will betray the secret.

Cronenberg enhances this sexuality — perhaps not consciously, but all the same — through Knightley’s startling unwhitening, taking advantage of the unconscious connections we make between sex and ethnicity.

Keira Knightley is, in most films, the picture of delicate whiteness. Few actresses possess a bone structure that embodies so well the swanlike beauty populating the dreams of Klansmen. But Sabina is Jewish, and here Knightley appears … less white than usual. The great unwhitening of Knightley is achieved by casting Sarah Gadon as Jung’s wife Emma. Gadon’s features are so beautifully delicate and small, she is more like a tracing of her own image than person herself.

When the film cuts to Knightley from Gadon, Knightley appears surprisingly strong. Brown. Masculine even.

This unwhitening allows her sexuality to grow unrestrained, for as the world has long shown us, the further you are from whiteness, the closer you are to libidinous mania.

It is extremely arousing to watch portrayals of sexual dysfunction. There is no joy in watching another person’s suffering, but the rearing of dark secret sexual power reminds of the mysteries of sexuality — the expanse that lies there untapped and, of course, its inherent relation to birth and death. We understand these things instinctively. The chill that overcomes us when seeing something dark, is the rapture of sensing, for a millisecond, that which exists before we are born and continues to exist after we die.