Jeff Jackson’s Destroy All Monsters bills itself as “The Last Rock Novel.” The novel declares rock and the rock ethos dead and invites its readers to pay their respects, but declaring that rock is dead is less a criticism than a celebration on the occasion of its passing. The plot is simple: In a small, nondescript American town called Arcadia, musicians are being murdered at their own concerts. The killings spread. The novel performs the mourning it invites, for a sound and a scene and a subculture that has run its course, officially eradicated now by, what? Technology? Capitalism? The forward march of human history? Jackson seems to want to be, and to want us to be, both the killer and the bereaved, saddened by the loss of this important art form but already tired of its endless reproduction as cheap product. He’s sorry to have to be the one to put rock out of its misery, but he knows it has to be done.

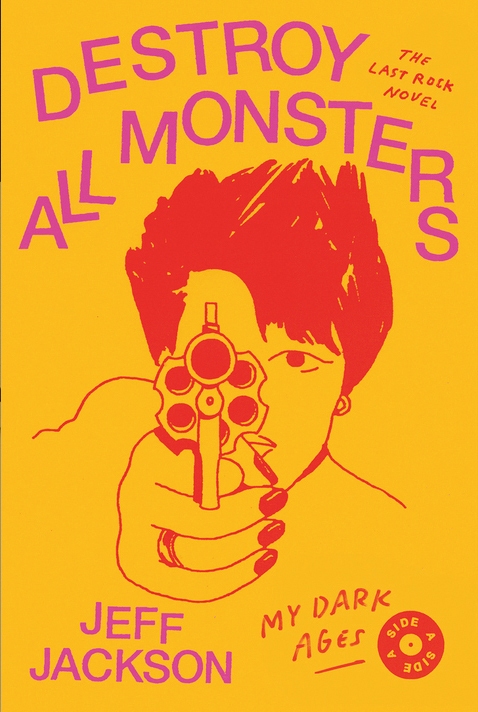

Jeff Jackson, Destroy All Monsters: The Last Rock Novel. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2018. 384 pages.

But if punk and rock have been dead for years, and we’ve all more or less accepted it as for the best, then Jackson isn’t mercy killing, he’s refusing to pull the plug. For a book ostensibly about the exhaustion and death of cliché, stylistically, Destroy All Monsters resorts to cliché startlingly often. The descriptions of the performing musicians, descriptions Jackson should presumably be able to write from some experience, use language that not even the most off-brand music blog would allow. At the height of the action, we find ourselves “watching the guitarist windmill his arm and strangle his microphone stand in time to the spastic beat.” Has any guitarist from any band that plays house shows ever windmilled? Jackson may not even realize how much he reproduces the rock mythos he is supposedly intent on destroying.

The admittedly violent atmosphere of Destroy All Monsters induces neither paranoia nor suspense. It shows its cards from the first page. The uncertainty that normally produces anxiety is replaced with proud certainty and tough posturing. You don’t get the chance to wonder whether anyone might die, or who. This book is hardcore, motherfucker. It’s called Destroy All Monsters, not Avoid Certain People. Everybody dies. Get ready. Jackson forgets that rock was a safe channel for unresolved fantasies of annihilation, not an exercise in creating violence where it doesn’t exist.

Destroy All Monsters was the name of a Godzilla film first, but the title reference is to the band of the same name, which mutated throughout the ’70s from conceptual noise art collective (featuring contemporary multimedia artist Mike Kelley) to underground party-rock outfit steered by ex-Stooge Ron Asheton. Based on the cover, a cheap imitation of the lowbrow flyer aesthetic of Kelley collaborator Raymond Pettibon, the novel is attempting to tap the spirit of Kelley’s incarnation of the group, but it ends up closer to Asheton’s. Pettibon’s captioned india-ink panels have elevated the punk aesthetic to a comprehensive iconography of American distress over the past few decades, and the works of Kelley, Paul McCarthy, and the others of their circle was consistently transgressive, confrontational, and disturbing. Jackson’s novel, by contrast, is slick, fun, and voyeuristic, and this is not a problem of translation between media. The era’s punk literature—Kathy Acker’s plagiarisms, Dennis Cooper’s fantasies of gay teen bloodlust, Richard Hell’s orgies of self-love—were twice as amateurish and twice as provocative, at least.

Jackson attempts to elevate Destroy All Monsters to Kelley and co.’s conceptual plane by experimenting with the novel’s composition, or at least its packaging. The novel is divided into two shorter novels, an A side, called “My Dark Ages,” and a B side, called “Kill City.” The book can be opened from either end and then flipped over, a move likely inspired by Mark Z. Danielewski’s experimental 2006 novel Only Revolutions, but more reminiscent of a special issue of MAD Magazine. “My Dark Ages” follows the friends of a musician named Shaun, who is an early casualty of the shootings. His ex-bandmate Florian and his ex-girlfriend Xenie haunt the scene hoping to find some way to resolve the senseless pain of his loss. “Kill City” is a sort of mirror world, like a Blue Öyster Cult song or Candyman, wherein the victims in “My Dark Ages” mourn for the friends who survived them. After a spooky funeral service for Xenie at which Shaun lobbies solemnly but unsuccessfully for her songs to be played, Shaun has a moody insight: “The evening feels unfinished. His mind keeps returning to the words about Xenie’s trapped spirit. During the past few days, he’s been visited by the uncanny feeling she is still nearby, somewhat slightly beyond his vision, on the flip side of this reality.” The attempt here must be to introduce some thematic play with duality and opposition, life and death. But the gimmick spoils it: On the other side of the book, literally, Xenie is alive and Shaun is dead. A trick like this is too obvious to be cool.

The ephemeral movement dubbed “alt lit” was a generation of writers’ first stab at retrofitting literature for the new millennium. For about five minutes, the “awkward” toxicity of Tao Lin and the babbling of Blake Butler seemed important to some. Jackson’s novel feels arrested at that first stage, or maybe just in Generation X. It’s not true that writing about music is never good; what’s truer is that good writing about music is never really about music. Novels about musicians can tell powerful stories about vice and dysfunction (Rick Moody’s Garden State), and novels about scenes and subcultures can delve fruitfully into politics and social theory (Justin Taylor’s The Gospel of Anarchy). In Destroy All Monsters, though, the violence is for its own sake. We don’t mourn the murdered characters, because we don’t know them. When Xenie and her new lover finally fuck at the end of “My Dark Ages,” the sex registers only as a structural climax, not as an eruption of actual feeling.

In high-school punk scenes, reference is the shorthand that makes it possible to make value judgments instantaneously, and therefore reference is everything. Knowing as much as or more than the next person replaces (in theory) class, talent, or any other variety of merit. In Destroy All Monsters, there are no references. The scenesters say things like, “I heard they’re going to play some punk classic,” or “they’ll play the songs off their first single . . . both the A-side and the B-side,” or “he bought me a single by a beloved soul singer.” Maybe the names are left out to avoid alienating the reader, but alienating people is what punks do. Without that, these kids have no claim to individuality.

Toward the end of “My Dark Ages,” a rationale for the killings emerges. The killers are pissed off that new music is commercial, that they can’t rely on it for potency or power. “The killers wanted music to matter again,” says Xenie. “It’s like they were thinning the herd, putting wounded animals out of their misery.” Xenie reveals that she sympathizes with the killers. She is also offended by the shittiness of contemporary music, and she wants to help with the cleansing. The scene faintly echoes Dennis Cooper’s Frisk, in which a teenage psychopath writes a long letter to his friend detailing his exploits murdering and dismembering innocent young men, and his friend responds approvingly. What makes Jackson’s reimagination of the scene so unconvincing is the suggestion that the rock purist angle affords it any depth. If you’re willing to kill for the integrity of rock music, you’re not offensive or dangerous, you’re a joke. There was a spate of killings on an underground rock scene in Scandinavia in the nineties, when the network of bands and fans that built the black metal community famously began murdering each other and setting churches on fire. The difference between this moment and Jackson’s Arcadia is that the killers on the black metal scene were pathologically antisocial white supremacists obsessed with the primordial violence of Nordic lore. There is nothing fundamentally twisted or threatening about the kids in Jackson’s book, no violence, just banality.

Punk rock, along with all of its exponents, is and always was, by definition and design, stupid. This is not an insult or a judgment but credit where credit is due. Punk was iconoclastic because it forced pop culture, and therefore capitalism, to adjust to meet new, hitherto unrecognized popular demands: nihilism, loathing, violence. This was not an insurrection but a test, and capitalism passed with flying colors. If punk accomplished anything, it was demonstrating that capitalism can sell anything, even its own antitheses. Now, thanks in part to the agitations of punk rock, we understand capitalism better. But putting a moratorium on punk, or rock, at this point isn’t going to accomplish any more or less than making more of it. Which is to say: not much.