The early days of the COVID-19 pandemic sent hospitals scrambling for necessary resources under normal operations: ventilators and other respiratory assistive devices, medications to keep patients on ventilators sedated, and, in some cases, even medical-grade oxygen. As patients of varying levels of sickness piled into emergency rooms, even the ability to be admitted to the hospital became a precious resource. I work as a physician, and I can remember admitting people with pneumonia from the ER in the ”before times,” when an oxygen saturation in the low-90s was worrying enough to potentially warrant a hospital bed. But COVID-19 created an entire new environment, and new standards for what constituted sick enough to qualify for a hospital bed. We started to send much sicker people home, with tanks of oxygen and a plan for a check-in phone call.

In any scenario—whether the chronic problem of determining who receives organ donations or the timely case of an uncontrolled viral pandemic spurred by state neglect—triage presents a brutal ethical dilemma. The criteria at the level of the individual (risk factors, social supports, likelihood of survival) become hard to justify once one centers social causes for illness. When you deny someone a liver because of their alcoholism, is that denial based on the individual’s addiction or the conditions that prompt one to become chemically dependent to cope with socioeconomic disadvantages? When you deny someone a ventilator, does your denial represent a bare fact of availability, despite the manufactured scarcity in hospital systems that prioritize profit over maintaining capacity to meet disasters?

Triage guidelines help assuage the guilt of caregivers faced with impossible decisions. As their patients inevitably die, or when the number of dying people outstrips the availability of life-saving interventions, abstracting decision-making away from healthcare workers can theoretically reduce their mental strain. It can even allow them to intellectualize deaths as a mere matter of scarcity and not something more sinister.

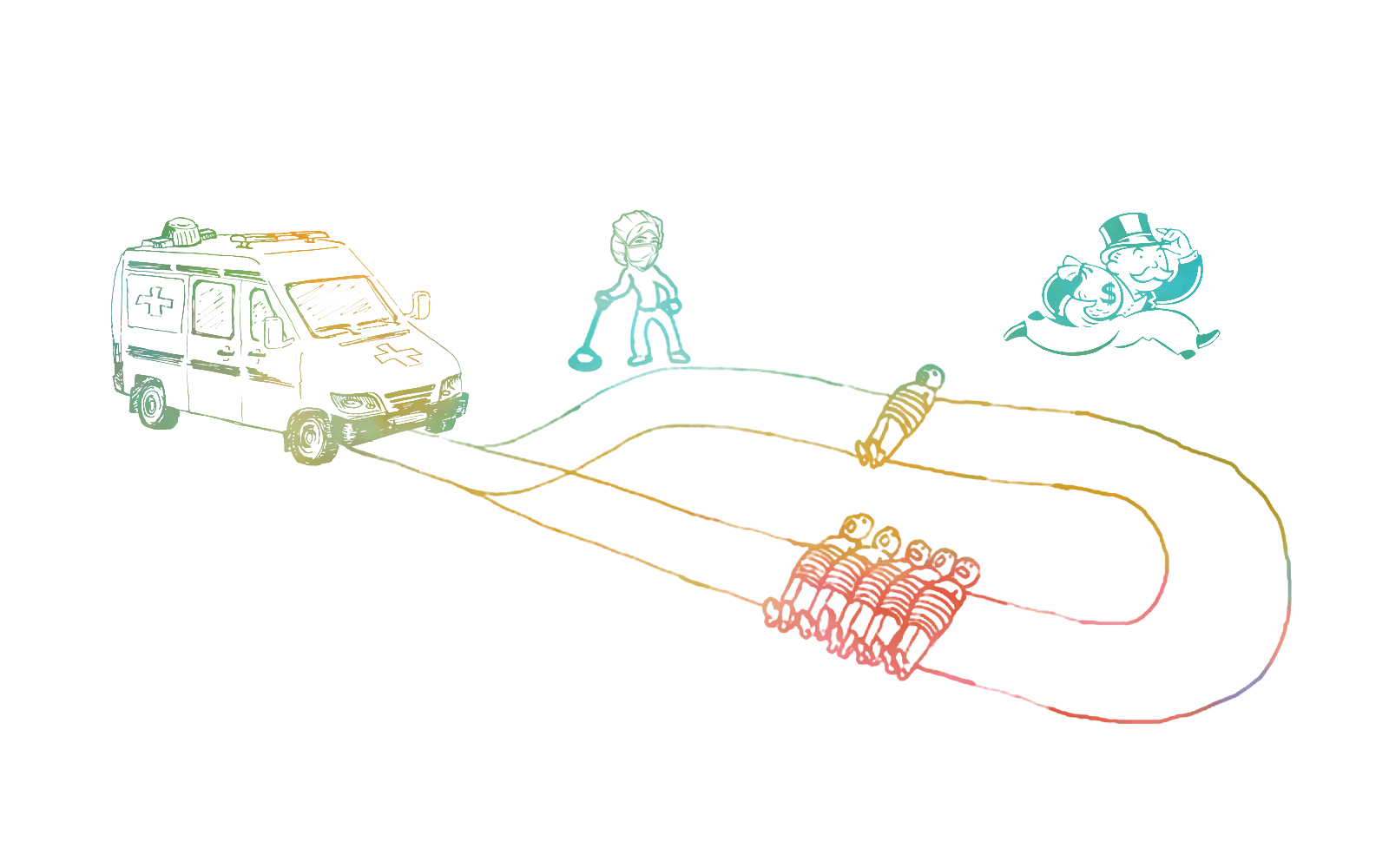

But there are missing pieces to that story, which can make it seem that triage is a “natural” and inevitable result of any crisis. First: resource scarcity is a function of hospital systems’ deliberately deprioritizing the flexibility to allow for crisis standards of care; and second, the number of cases and deaths reflects the impact of state decision-making, especially in the era of the Omicron variant. Faced with a strain capable of evading prior immunity, the Biden administration pushed onward with a vaccine-only strategy to the detriment of all, but especially to those forced into congregate housing or workplaces, to those with conditions that make them more vulnerable to the virus, and to the healthcare workers who confront the consequences.

For hospitals, maintaining a supply stockpile is a question of dollars and space. Respirators, ventilators, and other equipment for emergency life-saving care all require purchasing, storage, upkeep, and careful monitoring. Maintaining the systems that allow for crisis standards runs counter to hospital profiteering, and so those systems have been gradually stripped away. One massive setback early in the COVID response in the U.S. was the discovery that thousands of stored ventilators were nonfunctional. Staffing levels can also be oriented toward protecting a hospital’s relatively thin profit margins: Rather than leave a nurse on shift in case a flood of patients arrives, shifts are canceled or staff are sent home early if the staff-to-patient ratios fall below a certain threshold.

On the national level, public health as a federal priority has been gradually whittled away. While many cite Trump’s attack on Obama-era reforms, the Obama administration itself downplayed the early stages of the swine flu pandemic in 2009, focusing on vaccine development in lieu of containment. Distributing N95 respirators from the national stockpile to confront that crisis created a three-year shortfall, extended by environmental disasters like Hurricane Sandy and other major infectious disease threats like the Ebola and Zika virus outbreaks. Despite this, the administration appears to have not taken steps to speed the restoration of stockpiling.

At my hospital, triage evaluations of the first wave’s COVID patients were made largely through lab values and vitals —high white blood cell counts, very rapid or slow heart rates, and extremely high or low blood pressures could portend a worse outcome. If physicians thought these indicated that a patient was heading down the wrong path and had a slim chance of recovery, the doctors could potentially step in and begin de-escalating the most aggressive measures, like ventilators. Among considerations not strictly based on clinical data, though, was age. Other hospital systems included criteria like terminal illnesses or disabilities considered “life-limiting” in their COVID guidelines.

In some states, like Washington, a state-wide protocol recommended considering a patient’s “baseline functional status” —a vaguely defined term that per the state’s recommendations included “loss of reserves in energy , physical ability, cognition and general health”—in making resource rationing decisions. Disability rights advocates have rightly challenged many such protocols, which often deprioritize the lives of those living with physical or cognitive disabilities. Survey data has shown that physicians tend to rate disabled people’s quality of life as poorer than those people would rate their own quality of life. COVID triage situations that allow physicians to make value judgments about the utility of a patient’s care, like those put forward by Washington’s Department of Health, are not only discriminatory but potentially life-threatening.

I remember sitting in transplant team meetings, watching the staff decide who gets the gift of longer life based on factors that were beyond patients’ control: Do they have family home to help them? Do they have the money to pay for surgery, for medication, for ongoing medical care? If not--a disappointing click of the tongue, moving on, next soul.

Such is triage in a for-profit system, in a country devoid of support for its sick citizens. Such is the abstraction of human lives and the economic circumstances that so often enforce death upon our loved ones, the mandate of scarcity. It is the same mandate that leaves so many struggling for breath in the days of this pandemic, so many dying because some decision-maker far removed has consented to their death for them, through neglect enforced by policy.

However , physicians are not the only party involved in rationing care. Formulating triage guidelines at the hospital or state level involves multidisciplinary working groups. A major player in justifying triage on philosophical grounds has been a new kind of consultant that emerged in the late 20th century: the clinical ethicist. These are academic experts in ethical thinking as applied to dilemmas in health care, and their territory encompasses both writing and consulting on hot-button issues such as abortion, end-of-life, medical technology, and genetic engineering, as well as consultation on day-to-day struggles in hospital systems themselves. As the healthcare system has become an increasingly complex web of consultants, businesspeople, and clinicians, ethicists have become interpreters of personal values, hospital policy, and legal mandates for clinicians and patients struggling with difficult decisions.

While ethics consultants have existed at least since the 1980s, the American Society for Bioethics in the Humanities established core competencies for ethicists performing in-hospital consultations in the late ‘90s, and then set up a formal certification exam, the Healthcare Ethics Consultant Certification (HEC-C), in 2018 with the goal of enforcing minimum standards of knowledge and experience. Job postings for in-house hospital ethicists increasingly expect HEC-C certification or eligibility.

This contemporary brand of ethics consultation in the medical field is distinctly separated from the actual practice of academic ethical writing, where commentary often focuses on the kinds of topical issues like end-of-life care as mentioned above, but in a more theoretical way. A common academically oriented reading in curricula is Judith Jarvis Thompson’s famous “A Defense of Abortion,” where the author argues by a number of analogies, including “people-seeds” drifting into someone’s window and taking root, and the ethical obligation to care for such a person-seed. Much of the field’s teaching centers on theories that are at least morally opposed to profit-seeking as a primary end of health care.

Yet in taking fellowships, certifications, and allying themselves with hospital systems, bioethicists are brought out of the shadows of an academic discipline to become part of a capitalistic hospital structure. Ethics consultation is constrained by a medico-legal framework that strongly limits ethicists’ power to make pronouncements about ethical dilemmas without deferring to a hospital’s policies. Consultants would have a hard time justifying doing something outside this framework that could lead to a hospital or its staff being punished by the legal system, in the event of a decision being found medically negligent. In answering a question such as who deserves to be saved first, ethicists choose the path of least resistance; they deliberately devalue marginalized populations--the disabled, the elderly, the medically “complex” person carrying comorbidities and risk factors for COVID-19. In doing so, they may save resources, but they also implicitly reify thought processes that remove the disabled or the chronically ill from society. The flows of decision-making follow easily worn paths made previously by capital and the intrinsic valuation of those deemed healthy by the medical establishment. The non-productive, the surplus, those who are thought to contribute disproportionately to “healthcare expenditure,” are those who are first on the chopping block.

This is partly due to biases baked into the medical professions: as mentioned before, physicians tend to rate disabled people’s quality of life as worse than disabled people rate it themselves. But as healthcare professionals are increasingly made into a hospital system’s employees, the question of who holds the power, who signs the paychecks, and who crafts the decision-making policy in health care becomes more significant. Disagreeing too loudly with the system, and its suite of corporate leaders, might risk an otherwise secure career. If the hospital says it needs help sorting out resource allocation, and it seems to want a specific group of “risky” people to be deprioritized, it might seem reasonable for employees to go along. And on some level, it seems logical: If a group of people is more likely to die on paper than another group, one might think they should be deprioritized. But in an economic system that emphasizes metrics like “bed turnover rate”--the amount of patients who occupy a given bed in a hospital per year--as a sign of efficiency, can we trust that metrics are purely motivated by patient care goals or by how profits can be reduced by longer lengths of stay?

As the Biden administration waltzes toward a future where the coronavirus is part of a more general condition of permanent precarity, especially for those at society’s margins, Covid triage protocols raise the question of what professionalized bioethics are for. Is a bioethicist who is working in a hospital setting and rubber-stamping a protocol by which hospitals are permitted to allow certain people to die undermining the entire goal of ethical philosophy to interrogate how our lives are organized? Is a bioethicist who says yes to a rationing protocol even doing ethics?

In 1992, bioethicist Albert R. Jonsen warned that “ethics bears most stringently on those who have the ability to dominate and exploit.” Putting that another way, ethics is properly deployed to rein in the use of power. But in becoming intimately involved with the machinations of hospital systems, ethicists have made themselves adjuncts to that power.

Having ethicists among hospital staff may help clinicians with difficult decisions generally, but the ethicists serve a second purpose: protecting hospitals by shrouding their profit-oriented decisions in philosophical language and legitimacy. Once bioethicists become embedded in the politics and decision-making procedures of hospital systems, they run the risk of becoming complicit, reinforcing the economic and political logic by which such systems are allowed to exist. That is, they risk becoming participants in and beneficiaries of capitalist health care rather than potentially its most potent critics.

Certainly, many well-read ethicists may reject capitalist society but still feel that crisis standards for medicine are necessary. The pragmatist would view the development of such guidelines as mandatory. After all, we are short of hospital beds, staff, and ventilators right now. One cannot manage the current reality without crisis standards, and the pragmatic approach would be to simply deal with this reality as it exists. But acknowledging capitalism’s failings in the abstract does not mean ethicists will critique its consequences in practice: the structures that have led to bed crunches and ventilator scarcity, the government that prioritizes “shots in arms” PR campaigns over containment, the deadlier viral strains that stem from uncontrolled spread, the mounting death toll.

The need for justification of policy-based social murder has produced the sort of professional class of ethicist we see in corporate settings, including hospitals. I recall Google firing its head of “Ethical Artificial Intelligence” over a paper she authored about a specific type of AI, the large language model. Once she became critical of Google’s future business models, she became a threat rather than an asset to the company. While ostensibly hired to ensure ethical standards, these consultants exist as a kind of rubber stamp. When a hospital needs to say that their model for denying a certain type of care is just--be it hospital beds or ventilators or organs--they can hire an ethicist to write a policy booklet or cite those policies. In the face of such a system, how can such a thing as an ethical duty of care be achieved?

The question for ethicists with respect to triage--whether it refers to allocating scarce organs for transplant or scarce ventilators in a pandemic--pertains to the entire basis of how it is conceived: Should individual factors and individual health systems’ capacities be prioritized at the expense of the broader issues at play? That is, should triage itself be rejected if it lacks the just delivery of care as a first principle?

The most ethical thing might be not to sit across the table from administrators and form policies and guidelines, to tell people how to best decide who lives and who dies. It might instead be to demand the dignity and freedom of all the living and the dead, to fight the forces insisting untimely death is merely an unfortunate consequence of the overriding requirement to make money. It might be that an ethicist’s place in these times is not in a boardroom or a Zoom call but in the street.