In a grindhouse-grainy cinematic version of my life, I have both the money and know-how to restore muscle cars. I picture myself hopping in a cherry-red Charger, Firebird, or Camaro and sending it rocketing through suburban streets as Heart’s “Barracuda” plays on the stereo. Heedless of the expense or environmental impact of driving such a gas guzzler, I head for the desert, leaving lawns and inflatable pools behind — along with my responsibilities and notions of taste and decency. Among the sagebrush and spiny creatures the lusty wails of Ann Wilson give way to the great sun-glare and silence of desolate nature. I contemplate its vastness, feel it perch me teeteringly on the tip of some existential fulcrum.

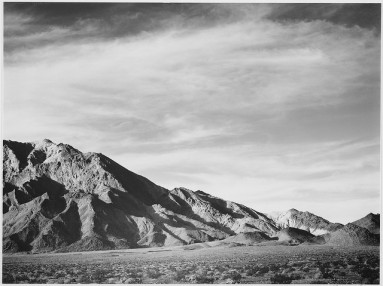

I wonder if Michel Foucault felt a similar impulse in the spring of 1975, when during a visit to California he agreed to drive out to Death Valley for one life-changing evening. There he would be “suspended among the forms hoping for nothing but the wind,” his American host promised. Initially skeptical, Foucault eventually came around to the idea. He perhaps wished also to pirouette upon that fulcrum, in the desolate and unendingly beautiful “Valley of Death,” as he, in his franglais, called it. His phrasing it in the genitive somehow captures the essence of the place: Death oversees the valley, is so clearly master.

***

If you drive down highways where signs warn, “Last Gas for 250 miles,” you realize how dependent your car is, how fragile your body is, how numerous your requirements for life. You remember that “deserts miss the rain,” as a woman misses her lover. Virga, the rain that evaporates before reaching the ground, sweeps and hovers over the desert floor, teasing and flirting with the plant life. Virga is rain unrealized, rain aborted. It’s not anything you can depend on.

If you happen to be tuned to Coast to Coast on the AM band, you might begin to believe that the odds of being abducted by aliens are greater than those of surviving a breakdown.

Originally broadcast from founder Art Bell’s own transmitter from his home-studio stronghold in Pahrump, Nevada, Coast to Coast, a late-night radio show, brings esoterica to truckers, third-shifters, and insomniacs. Numerology, prophecy, cryptids, shadowy cabals, past lives, string theory, rogue planets, ancient astronauts, giants.

His show inspired Crystal Gayle to record “Midnight in the Desert,” which ended up in heavy rotation on the show as bumper music:

Midnight in the desert and we’re listenin’ to you,

Midnight in the desert and there’s wisdom in the air.

I've been looking for the answers.

All my life I've felt you there.

As the world we live in quickens are we heeding all the signs?

Have we lost our intuition? Are we running out of time?

Your well-reasoned skepticism does nothing to ameliorate your vulnerability. If you happen to fiddle with the radio’s dial, you discover that the songs that appeal to you most are those whose lyrics have anticipated your present trials and crises and have stared them down.

This is not only a consequence of the threatening environs. The problem is as much the lack of population as the lack of flora and fauna. You die in the desert because there’s no one around to help you. The outlaw, the ex-con, the go-it-alone libertarian — who makes so bold to dance on the point of the fulcrum for life?

Foucault addresses this question in his 1967 lecture, “Of Other Spaces,” in which he defines and elaborates his concept of “heterotopia,” nonplaces “something like counter-sites,” that “designate, mirror, or reflect” society. These heterotopias are home to “the other,” housed within their designated “Other Spaces": a prison, a brothel, a cemetery. Within a heterotopia’s ambit, threatening and subversive elements and practices can be confined so that normal society may persist unimpeded. Naturally, they nestle themselves snugly into this otherwise unforgiving landscape, which serves as a bidirectional buffer.

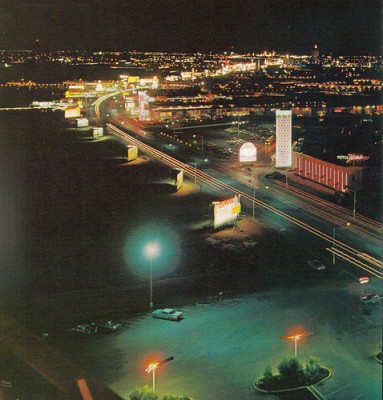

Las Vegas, a glittering oasis of polymorphous excess, exemplifies Foucault’s heterotopia of deviation, the peculiar essence of which is distilled in The Flying Burrito Brothers’ 1969 song, “Sin City”: “This old town’s filled with sin,” insists singer Gram Parsons with his distinctive twang. “It will swallow you in, if you’ve got some money to burn.” Irresistible is the lure of vice. Yet even “on the thirty-first floor” of some majestic casino hotel, “a gold plated door won’t keep out the Lord’s burning rain,” so great will His wrath be from having witnessed the goings-on. The band’s accompanying short promo film for the song juxtaposes images of prostitutes with those of hustling passersby. Intercut with these are shots of the band, sporting the finest in embroidered and fringed nudie suits, posing among Joshua Trees or before signs of flashing neon.

Vegas is both heterotopia and heterochrony, “a sort of perpetual and indefinite accumulation of time in an immobile place,” as Foucault defines it. He applies it to those locations where a “general archive” exists, one that exhibits “all epochs, all forms, all tastes ... outside of time and inaccessible to its ravages.” A museum is a heterochronic place, as is a library. Though not exactly a museum or library, Vegas is no less heterochronic: What happens there stays there, which means that sin after sin accumulates there and will do so indefinitely — or at least as long as sinners continue to visit. As those sinners depart Sin City they enjoy one last chance to see the physical place where their recently committed sins exist, perhaps as yet throbbing invisibly somewhere in the ethereal glow of the city’s never-quite-night night sky, which fades as they return to their nobler ordinary lives without hesitation or regret.

Sheryl Crowe sang about abandoning Vegas once overnight trips to Barstow failed to restore her. “Nowhere is far enough away” to suit her. Bang down any highway long enough, however, and you’re sure to find another heterotopia of deviance. They dot the landscape and come in many varieties.

Some heterotopias “seem to be pure and simple openings,” Foucault writes, “but ... generally hide curious exclusions.” Case in point: “the famous American motel rooms where a man goes with his car and his mistress.” “Cold Desert” by Kings of Leon recounts the solitary vigil of a man who malingers in the desert night waiting for light to shine in his lover’s bedroom window, a signal that she’s alone. The song suggests this waiting is routine — indeed, interminably so. The band’s performance emphasizes the tension within the ritual. They fade into an outro only to bring back the melody return at full volume — persistent, undead, never enough.

***

The desert residents of myth live out predestined lives of murder and brutality and then forgive themselves by mythologizing their feral intensity.

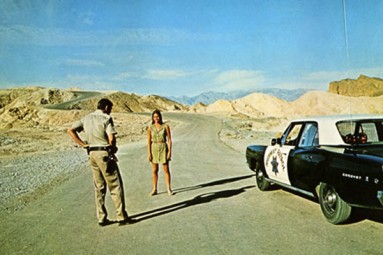

“There’s a killer on the road,” goes a line from the Doors’ “Riders on the Storm.” Popular media has taught us that murderers like to stalk roads less traveled in search of victims. Well outside of Las Vegas, Reno, or Carson City, runs U.S. Route 50, which Life once dubbed “the loneliest road in America.” The far-flung towns that hug it I imagine are full of ex-cons, prison guards, soldiers, veterans — all men who have been at one end of a gun or the other (or perhaps both). Traveling through such towns I’ve observed only men with crew cuts and confident gaits. One woman, so clearly an Other in a land of male Others, a Lilith among the other desert fauna, served me steak and eggs in the town of Beatty and had a name tag affixed to her dusty-rose diner uniform: “Virginia.”

A place just south of Hawthorne, Nevada, is home to an installment of munitions bunkers, neatly arranged like a suburban subdivision. Just southeast of Fallon, the land is pockmarked from years of fighter-pilot training. Pink Floyd’s “Get Your Filthy Hands Off My Desert” begins with an explosion, followed by a few cheerful notes sounded by a string quartet, perhaps celebrating the completion of military exercises bearing such names as “Hood,” “Smoky,” “Galileo” or “Operation Plumbbob.”

***

Joni Mitchell sensed the rich symbolic value of fighter planes. Her song “Amelia,” addressed to the famous aviatrix who disappeared over the Pacific Ocean in 1937, includes the following lines:

I was driving across the burning desert

When I spotted six jet planes

Leaving six white vapor trails across the bleak terrain

It was the hexagram of the heavens

it was the strings of my guitar

Amelia it was just a false alarm

These jets symbolize not war but a mystical hajj or hejira undertaken by one woman, inspiring the title of the 1976 album on which “Amelia” appears. Perpetually on tour at the time, Mitchell became a nonplace herself; always in transit, she was heterotopia made flesh.

The drone of flying engines is a song so wild and blue

It scrambles time and seasons if it gets thru to you

Then your life becomes a travelogue

Of picture post card charms

Amelia it was just a false alarm

I first heard Mitchell’s song in the American southwest, in a camper carrying my family and me to Monument Valley. Burdened with teenage disappointment, I, like Foucault, sought to suspend myself “among the forms” and hope for “nothing but the wind.” The seemingly endless salt flats beyond the camper window rolled by, interrupted only by concrete-walled and barb-wired who-knows-what. Festooning these were signs bearing dire warnings. Subject to felony charges. Up to $15,000 fine. Trespassers will be shot. What would be more confining, these enclosures or the vast empty spaces?

***

Prior to Foucault’s California visit, his host, historian Simeon Wade, sent him a letter in which he urges a trip to Death Valley. As the crux of his appeal Wade cites Antonin Artaud’s book, A Voyage to the Land of the Tarahumara, which details the author’s peyote visions. In the grips of heroin addiction, Artaud sought to cleanse himself of the nasty, tenacious spirits responsible for it. A “tongue of fire” would lick him clean, he had hoped. The suggestion of a ghostly tongue bath was perhaps too much for Foucault to swallow. He would have to think about it.

The exchange between Wade and Foucault leaves you wondering about the need for an invitation to the psychedelic rabbit hole. In “the land of the free,” it ought to be “come as you are.” Everyone is welcome, by definition. Yet many private or public parts of Death Valley and its environs maintain a clear entrance policy; inhabitants must gain access through layered security. Munitions-testing sites feature stern signs. What’s happening inside past the perimeter they leave unequivocal. Area 51, however, bears little signage. Even its buildings appear blurred in Google Maps, assured of anonymity like participants in a sex survey. You can only imagine the whispered passwords and retinal scans needed to gain entry.

“Heterotopias always presuppose a system of opening and closing that both isolates them and makes them penetrable,” Foucault observes.

In general, the heterotopic site is not freely accessible like a public place. Either the entry is compulsory, as in the case of entering a barracks or a prison, or else the individual has to submit to rites and purifications.

Eighteen or 21 are the typical ages at which most U.S. citizens perform such rites, whether they do so in legal brothels, casinos, and prisons or at military bases. Those who move from the civilian world to the compound must endure the training and conditioning that turns a man into a weapon.

So great is this intensity that it persists beyond the grave. The spirit haunting the Mizpah Hotel in Tonopah, Nevada, is a prostitute dressed in red, whose pimp chained her to a radiator once he discovered her pregnancy, then killed both mother and child shortly after the former’s labor pains subsided. Near Stovetop Wells campground wanders the spirit of Joe Simpson, a man lynched for robbing a bank in Skidoo, California (now a ghost town, fittingly enough).

So shaken was Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh by the 1993 FBI-ATF siege of the Branch Davidian compound near Waco, Texas, that he consoled himself by visiting various gun shows. Like the cult’s leader, David Koresh, McVeigh thought that events in the U.S. were moving to a crescendo. The end was nigh, and whether that meant the end of the world or of liberty mattered little to him. In his Waco compound Koresh taught his own brand of Adventist eschatology, which had been revealed to him during a desert sojourn and which he distilled into Voice of Fire, an album of songs released posthumously by Junior Motel Records.

***

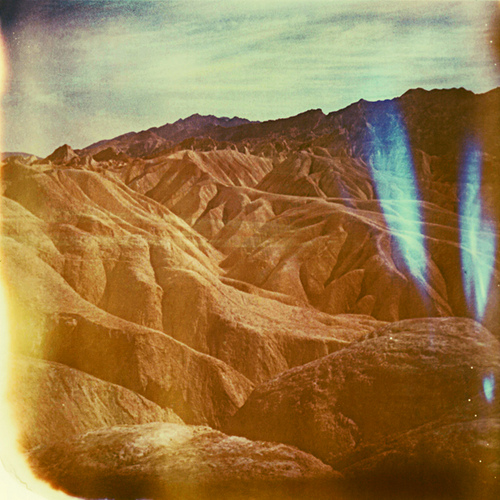

Darkness quickened as Foucault, Wade, and another person raced toward Zabriskie Point one night in May 1975. As Wade later recalled to Foucault’s biographer, James Miller, the bald Frenchman confessed to having never before done acid. He did have a clinical interest in the substance, believing it would advance a critique of “the distinction between the normal and the pathological,” as he claimed in an interview; but, alas, pure LSD was tough to come by in the City of Lights. As Foucault looked out the car window at creosote bushes zipping by, did he wonder what visions his chemically enhanced bit of California dreamin' would impart to him? Was he summoning bravery to face whatever it was he might discover?

As the LSD took hold, Foucault underwent what he called a “limit-experience,” which he defined as the line that separates the reasonable from the mad, the free from a white-padded room, logic from poetry, the cultural “other” from a homogeneous “us”; a line created by the systemic institutional entity familiarly known as “the Man,”, who, along with Plato, would certainly expel all poets from the republic for their counterproductive flights of fancy.

Miller claims that the desert trip inspired Foucault to apply more vigorously the idea of limit-experience. Critics later detected a shift in Foucault’s discourse from 1975 on.

If Foucault’s own psychic hejira reveals anything, it’s that the fulcrum found in the desert is also the fulcrum discovered within the self. The self makes the distinction between what is encouraged and taboo, logical and poetic, real and unreal, sane and mad. The lever, meanwhile, already exists within us, and it is our responsibility to pry open the perimeters, the fences, the grids, and the walls “the Man” has superadded to two-laned nothingness, to boundless, unstable soil. It may be as simple as goosing the gas on a muscle car as you head down some lost highway.