On September 27, TNI co-sponsored the one-day conference "Said is dead. Long live Said!" at City College that marked a decade since Edward Said's passing. Collected here are some of the talks, graciously provided by the speakers and organizers.

***

Ten years ago, the Palestinian intellectual and literary critic Edward Said passed away after enduring a long and difficult battle with chronic illness. Born in Jerusalem in 1935, a time when Palestine was under the British Mandate and there was not yet a State of Israel, Said grew up in colonial Cairo. In 1951, he was expelled from his British high school, just one year before the revolution that would eventually expel the British themselves from Egypt. He was sent to America to finish high school at a college-prep boarding school in Massachusetts, and went from there to Princeton and then to Harvard. Eventually, Said ended up down the street at Columbia University, where he taught for 40 years in the departments of English and Comparative Literature-- a fact that, I think it is fair to say, is one of those rare instances of institutional pride for those of us who currently find Columbia our own academic home.

In the last few weeks, there has been an outpouring of tributes for Said, full of moving reminders of the mark he left in the lives of so many people around us. Said is remembered for his unique combination of groundbreaking scholarship and fierce public engagement, unshakeable charisma and unsparing criticism, and always, and still, for The Question of Palestine. I cannot count the number of conversations I have found myself in over the years where we attempt to come up with a list of public intellectuals that exemplify the kind of engaged thought we need to confront our violent times. Always Said’s name is present, as is our debt to him in his absence. For this reason alone, his cautions to those of us located in the academy bear repeating here: that disciplinary rigour is not the same as exclusivist specialization, that no amount of writing is a substitute for a commitment to one’s students, and that the professionalization of both teaching and scholarship, as if intellectual life was a 9-5 job, leaves all of us poorer.

But the academy is not what it was. It is hard to find a humanities professor with so much style; whose writings have so deeply altered ways of thinking that, even if in disagreement, they are impossible to ignore; and whose principled political stances make him the person you would want as your guest speaker when you organize an antiwar rally. But it is almost just as hard to imagine that the university could sustain and nourish such a figure, rather than attempt to censure and silence them. The current ‘crisis of higher education’ in North America is reflected in many of our own experiences. In this country, education itself is increasingly being privatized, and the university continues to sink to new depths in its profit-seeking exploitation of students, teachers, workers, and entire neighbourhoods. As Thomas Frank has written, the utopia known as the American university, supposedly the finest educational institution in the world, is more like a disaster characterized by predatory capitalism, elitism, branding, and business management theory. It’s worth reminding ourselves that on average three-quarters of teaching at our universities is done by adjuncts, often making less than minimum wage. It is in this sense too, then, that Said is gone. The world that produced him and the conditions that nurtured him, fraught as they were, are not those of our times. But in the words of a former student of his, “remembering Edward Said forces us to think like him, in his place. The question after Said is, “how do we begin, again?”

When we conceived of the idea for this event, it was important that it not be an event about Edward Said himself. We wanted instead to use this opportunity to think about the many places where the spirit of Said lives on, even when he is not named. The thought and practice of Said are present in a huge range of contexts, from the work of street artists and hip-hop musicians to vibrant virtual communities that live in a constant exchange of words, images, songs, political opinions, and passionate debate. Of course, the forms that public-intellectual life take have never been limited to the academy. But I think it is unquestionable that changes in the university system, together with not only the technical developments but also the ethical demands placed on us by this increasingly interconnected world, mean that counter-cultural ideas continue to take new forms. In his 1993 lectures on the role of the intellectual that offered the inspiration for this event, Said says that intellectual representations are about “the activity itself, dependent on a kind of consciousness that is skeptical, engaged, [and] unremittingly devoted to ... investigation and ... judgment." Rather than bring together individuals who are already affiliated with Edward Said, we wanted to push ourselves and you to find in their art, their writing, and their activism a praxis that speaks to the nature of intellectual life in 2013 -- and that might also have something to say to Said’s own work. We are both honoured and excited that they could all join us.

There is a story Said tells in his beautiful memoir, Out of Place. It begins with his family doctor, Dr. Wadie Baz Haddad. Dr. Haddad lived in Shubra, one of Cairo’s poorest neighbourhoods, and is described to us as one of the many unsung heroes of the city’s cultural history. Somehow, Dr. Haddad managed to be both never in one place but always available, his home open to anyone who wanted to see him with no need for appointment, and always free of charge. After he died, his son Farid continued his practice with what Said describes as the same unselfconscious commitment, but one difference: Farid wore his politics in public. A Communist, Farid was later imprisoned for his clandestine work in the 50s, and Said attempts to piece together his story many years later. But this is how Said describes an earlier memory: “When I was about eighteen and a Princeton freshman, oddly combining the appearance of a crew-cut American undergraduate and an upper-bourgeois colonial Arab interested in the Palestinian poor, I recall [Farid’s] pleasant smile when I tried to question him about what his work and political life “meant”. “We must have a cup of coffee together to discuss that,” he said as he headed for the door.”

That cup of coffee is precisely the space that Said opens for us: to come with all our contradictions, histories, and interests to a conversation that struggles with complexity. We hope you enjoy it.

***

Restoring the Blood to Words, Martín Espada

I’ve always had trouble calling myself an intellectual. This reluctance does not spring from humility, as any of my friends or enemies could tell you. Rather, I’ve identified myself as an advocate, in my work both as a poet and tenant lawyer. Yet, advocacy is exactly what Said has in mind when he uses the term “intellectual” in his essay, Representations of the Intellectual.

Once I made the transition from tenant lawyer to professor of English, I was alienated from the “post-modern intellectuals” all around me. They were, as Said says, “admitting their own lazy incapacities,” though they defended that laziness with great fury. Said quotes the sociologist C. Wright Mills: “The independent artist and intellectual are among the few remaining personalities equipped to resist and fight the stereotyping and consequent death of genuinely living beings.” Said goes on to say that we must provide “what Mills calls ‘unmaskings,’ or alternative versions in which to the best of one’s ability the intellectual tries to tell the truth.”

That’s what I try to do as a poet. If phrases like weapons of mass destruction or drone strike bleed language of its meaning, then poets must reconcile language with meaning and restore the blood to words. I belong to the intellectual tradition of Walt Whitman and Pablo Neruda. Whitman speaks for what he calls, “the rights of them the others are down upon.” Neruda, who died forty years ago, says:

Let us sit down soon to eat

with all those who haven't eaten;

let us spread great tablecloths,

put salt in the lakes of the world,

set up planetary bakeries,

tables with strawberries in snow,

and a plate like the moon itself

from which we all can eat.

For now I ask no more

than the justice of eating.

***

Strong People Don't Need Strong Leaders, Robyn C. Spencer

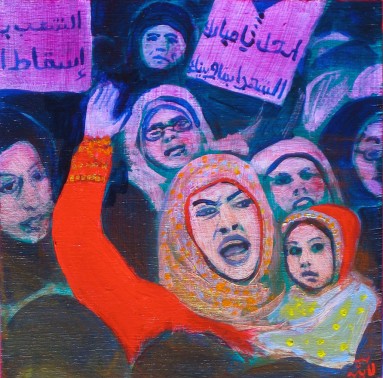

Today when we find ourselves bearing witness to the absolute continuation of ferocious struggle, resistance, the question of the role of intellectuals has never been more urgent. Said's writings are instructive.

The access of people to outlets and mediums to produce or disseminate knowledge, the work of intellectuals, has never been more open--blogs, facebook posts join books, public lectures, twitter and journalism yet there is also a troubling narrowing. Some intellectuals have been subcontracted as professionalized pundits who appear not just often to represent marginalized communities in public discourse but to replace/displace those communities. Serving as silencers even as they purport to amplify. Taking up room, rather than stepping aside. Expertise is a heady drug and comes with a side of privilege. One the one hand, I applaud those who duel in the realm of ideas. On the other hand, I remember Ella Baker simple yet profound wisdom: "Strong people don't need strong leaders."

We must never forget the very function of the academy is displacement, removal, separation and inculcation of values of individualism.

To quote Said:

The intellectuals’ representations–what he or she represents and how those ideas are represented to an audience–are always tied to and ought to remain an organic part of an ongoing experience in society: of the poor, the disadvantaged, the voiceless, the unrepresented, the powerless.

For me that means personally, that I must resist escalating out of the first generation immigrant/first generation college student experience and remain grounded in poor communities if I ever hope to be a legitimate voice for their ongoing concerns. Otherwise, am I not just a rapper who raps about experiences I am no longer viscerally connected to for mass audience/adulation/appeal? So, yes. Send your baby to that public school. Walk the streets where not just stop and frisk, but crime and avoiding victimization, are front and center in ones imagination. Conduct retail through the bullet proof glass and confront the mix of feelings about self and society that engenders. War, checkpoints, displacement and detention will not seem that far off.

Palestine, the struggle of Said's heart, will come into sharper focus along with Chicago and Harlem and East New York. That, to me is the "organic" part of what Said is talking about. How to keep a present tense stake in communities of struggle, even when you have the seductive option to escalate up and out. Said used his position at Columbia University as a platform to the world, facing the many personal and professional sacrifices of a life of activist scholarship. He became a voice for the aspirations of the Palestinian people. He reminds me to use privilege and intellect to not to take up all the air. To sometimes be a mirror. Be a drum that doesn't just beat itself but amplifies other intellectuals who may lack the mainstream credentials but who have more than enough expertise to be spokes peoples. "Be unwilling to accept easy formulas or ready made cliches" and be "actively willing to say so in public." It is a challenge not only to speak truth to power but a personal challenge to "balance the problem of one's selfhood."

I also see Said's words as a reminder. Sites of knowledge can themselves be organic. Try to remix the teacher/student role and amplify the school of everyday life. In a real sense that means supporting community based efforts to not only discuss power and politics but to do something about it. And accepting that in the best traditions of Said that sometimes your "role" may not be to lead but to let others lead.

Said was a humanist. He remained a profound optimist and enamored with the human connection. He not only wrote, for intellectual and public audiences -- I believe my first encounter with him was in the pages of "The Nation" magazine. He organized and built. These face to face human connections and real life political organization today are sometimes undervalued given what seems like the vast possibility of the world wide wonder of the internet. Said was a sharp critic, but always a loving one. He was both drum and mirror, both teacher and student. To quote Tariq Ali, "His voice is irreplaceable, but his legacy will endure. He has many lives ahead of him."

***

The Popularity That Comes With Unpopularity, Daisy Rockwell

In March 2012 an article about my paintings of terrorists was published on a blog on CNN’s website. The article quickly drew hundreds of mostly extremely negative comments. The comments were less in reaction to the content of the article than to the title: “Norman Rockwell’s granddaughter paints terrorists.” The commenters saw me as a terrorist sympathizer, which is bad enough, but also as an ungrateful granddaughter desecrating the legacy of her grandfather.

This legacy is of course a symbolic one, built over decades by the Republican Party and social conservatives, and bears little resemblance to the actual paintings of my grandfather, who strove to maintain an apolitical stance in his work, but showed clear sympathies toward the policies of the New Deal. My first reaction to these comments, which I tried not to read, was revulsion. I felt invaded and unsafe. But quickly those feelings were altered by the overwhelmingly positive responses I received via email and social media. I was invited to give a number of talks about my terrorism series at universities. In the end, the result of all those venomous comments was an increased popularity for my work.

I share this anecdote because I thought of it when reading Said’s discussion of the work and nature of the intellectual. He returns to the notion of unpopularity several times in the piece, and even closes his essay with the phrase “...but you may not be popular.” At first I found this preoccupation with unpopularity disingenuous coming from a man who changed the field of literary criticism, held a prestigious post at Columbia University and is spoken of in the most reverent of tones on campuses across the world. But of course there is another side: there is Said’s active and vocal support for the cause of Palestine, a cause that he perhaps more than any other public figure has brought into the spotlight of international attention. His popularity and his credibility as a distinguished university professor helped to make the Palestinian struggle a cause célèbre with activists around the world. Both this advocacy and his critical readings of Orientalist literature have been double-edged swords. They helped him earn immense adulation, but also vehement hatred from those who opposed his views.

Clearly it was this hatred that bothered Said and that he recognized as the burden he had to bear in order to continue to speak and write about the issues that animated him. At the same time, as my own experiences have taught me on a very small scale, it is inspiring and motivating for others to watch the fight between someone whom they feel speaks an important but subversive truth and those who feel angered by that truth. What Said does not acknowledge in his essay is that that unpopularity, which, in the case of a public figure, will manifest as a public battle, or even a war, is what lends the intellectual his credibility and allows him to strengthen his message for his audience. For me, the danger in this is allowing one’s self to be seduced by the popularity that comes with unpopularity. In art, at least, one must constantly strive to avoid allowing one’s work to become a facsimile of itself. Too much fame can lead to schtick, and this is why Said remarks in his essay that one should think of the intellectual vocation as “maintaining a state of constant alertness, of a perpetual willingness not to let half-truths and received ideas steer one along.” That state of constant alertness is one of the most essential skills in the work of the public intellectual. It is a state from which one can easily be seduced by adulation and complacency.

***

Returning History to the News, Anjali Kamat

Re-reading Edward Said’s Reith Lectures on the tenth anniversary of his passing, I’m struck by the heightened relevance of his blistering critique of the professional intellectual: a master in the art of “political trimming” – the “technique of not taking a clear position but surviving handsomely” – and of never rocking the boat. In a media landscape defined by mediocrity and where news coverage routinely involves willful simplification, the professional intellectual is a familiar creature. They dominate the airwaves – and large parts of the Internet – and show little outrage over the rolling back of rights and freedoms in this country, let alone US complicity in repression anywhere else.

I’ve always identified with Said’s notion of the intellectual as exile, occupying a contrarian if lonely position on the margins, not really fitting in with the mainstream, refusing to simply conform to what is practical or acceptable to those in power, and pushing back against what he called a “gregarious tolerance” for the way things are. But in the twenty years since Said’s Reith lectures, in some ways, New York has become a less lonely place for undomesticated intellectuals. Despite the bloated security state and the proliferation of the professional intellectual, the appetite for challenging authority has also grown apace. I’ve been personally lucky to find a home in Amy Goodman’s Democracy Now! and more recently, Fault Lines, where the emphasis is on telling stories from the perspective of the marginalized, returning history to the news, and, in their own small way, speaking truth to power.

But we do live in a moment when, for example, what happens in Cairo reverberates in New York and around the world. The old certainties about the longevity of American empire are changing, and the initial excitement and hope of the Arab spring have been harshly tempered. Speaking truth to power in this context of crisis and emergency can come at very great personal cost – whether you’re a whistleblower in the United States, or an outspoken activist in North Africa. It also necessarily involves challenging a few different gods at once, whose alliances with each other are not always clear, and constantly shifting. In this confusing time I’ve found comfort in the internationalism of Said’s vision, his injunction against looking to any orthodoxy for unwavering guidance, and keeping space open for doubt “without hardening into a kind of automaton acting at the behest of a system or method.” Perhaps all we can do then is commit ourselves to struggles beyond the categories of location or identity, and try to represent the truth to the best of our ability without being subservient to any authority.

***

Unpacking Empire Again, Esmat Elhalaby

First, a joke:

In The Bridge: The Life and Rise of Barack Obama, David Remnick, editor of the The New Yorker (and early supporter of the 2003 invasion of Iraq, as a Liberal does) wrote: Obama’s academic emphasis was on political science — particularly foreign policy, social issues, political theory, and American history — but he also took a course in modern fiction with Edward Said. Best known for his advocacy of the Palestinian cause, and his academic excoriation of the Eurocentric “Orientalism” practiced by Western authors and scholars, Said had done important work in literary criticism and theory. And yet, Said’s theoretical approach in the course left Obama cold. “My whole thing, and Barack had a similar view, was that we would rather read Shakespeare’s plays than the criticism,” [Obama’s friend Phil] Boerner said. “Said was more interested in the literary theory, which didn’t appeal to Barack or me.” Obama referred to Said as a “flake.”

I.

“As we don’t know the difference between a mosque and a university, because they are both from the same root in Arabic, why do we need the state, since states pass just as surely as time.”

— Mahmoud Darwish, “From now on you are somebody else”

Edward Wadie Said, for everyone except for Commentary magazine and its loyal readers, was born in Jerusalem, spent his childhood in Cairo, and moved to the United States as a teen. The United States was where Edward Said lived for most of his life. The racist, imperialist, genocidal United States was where Edward Said lived for most of his life. “When I say ‘my country’ to some Haitians,” Edwidge Danticat writes in the The Immigrant Artist at Work, “they think I mean the United States. When I say ‘my country’ to some Americans, they think I mean Haiti.”

II.

"To be a human being is the main thing, above all else."

— Rosa Luxemburg in a letter to Mathilde Wurm, December 28, 1916

At the 1986 meeting of Middle East Studies Association, Edward Said and Bernard Lewis,

Another joke:

In 1994, Ernest Gellner wrote a critical review of Said’s Culture and Imperialism for the Times Literary Supplement. Gellner, a noted anthropologist, orientalist, and apologist for empire, ended the review, which mischaracterized not only Said’s book but also Frantz Fanon’s role in the FLN (which Eqbal Ahmad would later correct in a letter to the TLS), by writing “The problem of power and culture, and their turbulent relations during the great metamorphosis of our social world, is too important to be left to lit crit.”

III.

In an interview with Elias Sanbar in the May 8-9, 1982 edition of Libération,

IV.

“I was tryna be a novelist / but who fuckin reads books? Be honest.”

— Kool A.D. “Exotische Kunst”

Thuggee Cult was never supposed to happen. Thuggee Cult was forced to happen when 5 friends, mostly the sons of immigrants, spent the summer of 2012 in close quarters in a wealthy part of Los Angeles, California. A university had brought them there. 2012

Thuggee Cult was never supposed to happen. Thuggee Cult would have never happened if it wasn't for the writings or the countless Youtube clips of Edward Said. Thuggee Cult would have never happened if we weren’t convinced that going to school and going about your business and not causing any trouble wasn’t just tragic, but unacceptable.

***

Lineages of the Possible, Shahnaz Rouse

I would like to bracket my remarks on Edward Said’s legacy today, with a narration of personal encounters with Said, which have left an indelible mark. The first was reading Said’s Orientalism soon after its publication. It made me deeply aware of what is now commonplace in critical circles, that is, that knowledge produces its object. For me, it raised questions about how knowledge is produced, what interests it serves and about disciplinary separations within the academy. I realized that to leave unexamined the premises of our own disciplinary training is to produce certain ‘realities’ which numb even critical thought. In the social sciences in particular, disciplines serve to alienate us from seeing our modes of classification and categorization as limited, being themselves the product of particular histories.

While this is central to Said’s analysis in Orientalism, his work too at moments fails to sustain this critique and reifies the very categories of East and West that are the object of his critique. In our intellectual and political projects this awareness demands of us both vigilance and humility. This cautionary note notwithstanding, Orientalism, and the connection it traces between representation and actual violence that attaches to it, resonates even more powerfully in a post 9/11 world, where the binaries that were productive of the Orient, and which Said so brilliantly elucidated, constitute the grounds on which violence is justified by state actors especially the U.S. and Israel. It is the objectification and dehumanization of ‘the other’ that serves as alibi for both military (ad)ventures and the neoliberal project, whereby both rely on tropes of freedom, democracy, choice. In a ‘world turned upside down’, representations that are the opposite of what they purport to be, invite us to accept the logic of market and military interventions, producing an ever more polarized world.

A more intimate encounter with Said for me occurred at a meeting organized by the Pakistan Committee for Democracy and Justice in New York City, where Said was the keynote speaker. It coincided with the Sabra and Shatila massacres in Beirut. Noticeably pained, Said lucidly analyzed the alternatives open to Palestinians, and in a very prescient analysis foretold the ‘first’ intifada. Years later, post-Oslo, I attended a talk by Said at the American University in Cairo, in which he critiqued not only the Oslo accords but also the PLO leadership, explained his resignation from the PNC, and argued that a one-state solution was the only option for both Israelis and Palestinians. That this was anathema to some Arab nationalists in the audience did not deter him. Taken together these two talks signify Said’s ability to imagine a different universe and a different politics, to enunciate alternative possibilities beyond those popularly conceived as possible. This is what made these encounters especially powerful.

In our unipolar world, where dissent is under assault in the name of ‘security’, where the privatization of the academy and further professional specialization is being imposed in the academic market place, spaces for critical thinking are increasingly constricted. Commitment to a critical practice, and the courage to construct alternatives to those presented by/in the present, is ever more essential. This is the task of the public intellectual today, whether within or outside the academy: to resist what is, what is given to us, and to use the venues of the word, the image, the technologies available to us to collaborate in the fashioning of a world that resists our disciplining and allows us to escape the confines of what’s seen as both real and possible.

The Gift is in the Wound, Chee Malabar

I don’t consider myself an intellectual in the strict sense of the word. Intellect suggests an engagement with oneself and the world from the neck up, and says nothing about the heart and gut—those deep places of spirit and lived experience. In an essay, Said says,

“Politics is everywhere; there can be no escape into the realms of pure art and thought or, for that matter, into the realm of disinterested objectivity or transcendental theory."

This quote rhymes with my experience as a youth worker in juvenile prisons and as an artist. My western education has emphasized the cultivation of the mind and has paid little attention to the cultivation of my heart and emotion. In my early years of doing this work, I’d enter spaces armed with the former, but quickly realized, while hearing stories of deep abuse, violence, and trauma, that I hadn’t done much soul work, that thing that moves beyond language and strikes at something richer; more alive. I was forced to listen with my heart and also work through my own trauma. I have since realized that in my art and community work, my mind has to serve my heart. This begins with creating spaces where one can tell their own stories without judgment.

Stories are the fabric that cross cut and weave us together--when we are unable to tell our stories or don't feel like we have permission to tell them, we suffer. In my work, I'm less interested in the political dialogues happening about laws, incarceration rates, etc. Not that they are not important, but numbers are impersonal. The incarceration numbers are gaudy and it becomes easy to be overwhelmed by them and set it aside out of its sheer size and breadth, but, when we are in spaces where we allow ourselves to hear and share stories, we become mirrors for each other and also witnesses to each other's lives. This has, I’ve found, a deeper impact on how we relate to each other whether we are within or apart from the dominant culture.

The gift is in the wound. If we begin to make our way toward the pain and trauma, we can discover our true gifts, that thing that we are meant to do and be in the world. This was true I think for Edward Said, who explored his own personal wounds of exile and pain, and in doing so was able to open a gateway to the cultural trauma of many marginalized societies around the world. His gift was his ability to give us a prism through which to view our shared global wounds. Edward Said taught us that we all must be vigilant and continue to heal ourselves if we are to be mirrors for one another and co-create the type of world where we want to live.

***

Fifth Columnists in the Academy, Snehal Shingavi

In 2000, when the second Intifada was starting up, I only knew of the Edward Said of Culture and Imperialism and Orientalism—two books I had encountered as a part of my undergraduate education, but had become common in my graduate English classes, too. At the time, a number of us at Berkeley were getting together to organize the Students for Justice in Palestine and to talk about how best to organize solidarity with the second Intifada and the aspirations of Palestinians for an end to the fifty-plus years of the Occupation. Many of us had been remarking how strange it was that students were having to learn the history and the politics of the middle East from scratch, given that our activist vocabularies and training had been drawn primarily from the anti-globalization movement. But we were also wondering how it came to be that the politics of third world solidarity which had been so central to campus life in the 1960s and 1970s had disappeared more or less altogether by 2000.

It was in that context that we rediscovered Edward Said, or rather, we discovered the other Edward Said, the one who had so brilliantly married political engagement with philological critical practice. This was the Edward Said of The Question of Palestine, The End of the Peace Process, and The Politics of Dispossession. It was also the Edward Said who was one of the first critics of Islamophobia in his marvelous reading of media practices in Covering Islam. It was the Edward Said who was ruthlessly criticized in the press for the harmlessly symbolic act of throwing a stone at an Israeli tank in solidarity with the young men and boys who became famous for their audacity to do the same. At a time when academics had mostly retreated from activist engagement, it was astonishing to find a scholar who had managed to work his scholarship out of his commitment to a deep politics of solidarity.

It was also a time when the assault on any academic who did not tow the pro-Israeli line of the American establishment was made to pay a price professionally and personally. And those of us who had the temerity to teach about Palestine or put Edward Said on our syllabi were branded fifth columnists in the academy. Hamid Dabashi, Joseph Massad, John Esposito, Juan Cole, and I were among the original group of academics who were placed on Daniel Pipes’ Campus Watch website for teaching material that was critical of American and Israeli policies in the Middle East. I do not believe that I would have been able to withstand both the political and the personal toll that such a shrinking of the mental and political horizons that happened between 2000 and 2001 without the political and the academic contributions of someone like Edward Said. Despite its many (and my own) flaws, I was proud to have taught the Politics and Poetics of Palestinian Resistance as a course at UC Berkeley.

***

Afterward, Conor Tomás Reed

The first time I set foot on the City College of New York campus was for a protest. During the Spring of 2005, four students and a staff member held a peaceful picket in front of a military recruiters’ table at a campus career fair. As a result, they were brutally assaulted by CUNY security. One had his face smashed into a concrete wall. Another – all five-feet one-inch of her – was pinned to the ground by several guards and handcuffed. At this assembly a few days later, speakers connected the occupations in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Palestine abroad with repression at home. Many alluded to a long radical history of CUNY that involved poor people of color taking direct action to shape their institution and communities. The favored chant – “Free CUNY!” – has resounded in my ears ever since as both a demand and a promise.

As a student here between 2006 and 2010, I began to learn about the histories nestled around this campus. In the 1930s, European immigrant students, who brought vibrant political traditions with them to New York, would chain themselves to the flagpole in the quad over there and deliver anti-fascist speeches. The cafeteria was electrified with daily debates on strategies of world revolution, anti-racism, eviction defense, community relief work. During the Spanish Civil War in the late 1930s, at least 60 students and faculty joined the Abraham Lincoln Brigades, including a student body president. You’ll find a small plaque honoring those who died in the North Academic Center rotunda. Look for the Guernica lantern being held aloft.

Over the next few decades, the school became a predominantly white middle-class moderate campus. By the late 1960s, this school right in the middle of the intensely dynamized community of Harlem had only 9% Black and Puerto Rican students, many of whom admitted through a visionary college preparedness program called SEEK. However, within a few turbulent years, SEEK became a nucleus for counteracting the inequalities entrenched in City College’s admissions, curricula, value systems, and relationship to the neighborhood. Through the work of Mina Shaughnessy, Adrienne Rich, June Jordan, Toni Cade Bambara, Audre Lorde, David Henderson, and others, the practice of socially engaged writing with these students of color created a space for radical experimental collaboration. This localized, decolonial, pedagogical process would soon transform CUNY and composition studies nationwide.

The 1969 Black and Puerto Rican student takeover of 17 campus buildings—modeled on methods used in the Algerian war of independence—created Harlem University for two weeks, animating five demands that included the creation of a school of Third World Studies, an anti-colonial freshman orientation program, and that the racial composition of all entering classes reflect the Black, Puerto Rican, and Asian population of the New York City high schools. While the CUNY administration dragged its heels on welcoming this new curricula, it moved to swiftly and unsustainably create “Open Admissions”—allowing every New York City high school graduate a place in one of CUNY's two- or four-year colleges by Fall 1970. This post-strike educational policy long considered to be a hallmark of CUNY's radical successes was, I'd argue, in fact a calculated form of institutional reform-as-sabotage. The entire campus, and the SEEK program in particular, became inundated, embattled, and under-resourced right at the point when they were providing an exceptional new model for what engaged writing and campus/community life could look like.

I briefly lay out these few periods for you tonight to show that the project of theoretical, historical, and applied decolonization to which Edward Said dedicated so much of his life is also right here… and unfinished: in our classrooms, our schools, our communities, and our relations to each other. With the teaching appointment of General David Petraeus, the return of ROTC, weapons research on our campuses, surveillance of Muslim students, and the continual repression of peaceful dissent, we have much work to do. So may our dialogue tonight both honor and continue Said's legacy to highlight why and how “education is a practice of freedom,” in the words of another City College teacher, bell hooks. Welcome to Harlem University. Long live Said!