I have never seen Franko B perform in person. I have never beheld any objects he has made. But I think I love him.

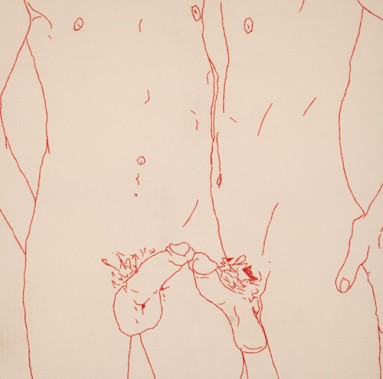

I love the way he looks. I love his pot belly, which has swollen out shamelessly over the course of his career; I love his dangling uncircumcised penis; I love the red cross tattooed on his forehead; I love the way his gold teeth hang out of his mouth; I love the sound of his gravelly lisping voice.

After all, we don’t talk much about love in contemporary art. Love is reserved for other genres — pop songs, movies, novels, poetry — but not art, certainly not conceptual art of the chin-scratching variety. But Franko B is unabashedly sentimental in his gestures. He twists slogans like ‘My heart is yours, do you want it?’ into red neon; he nuzzles puppy dogs and polar bears; he stitches flowers in full bloom onto canvas in red thread. Working equally in performance, painting, photography, collage, and installation, Franko B reminds the art world of the stickiness and ickiness of love.

I think of Franko B as something of an ambassador for love — or rather, its aftermath. When love gathers its things and goes, what does it leave behind? What are your symptoms? A bruised ego, perhaps. Regret, loneliness, self-indulgence, nostalgia: His work reckons with these ghost pains, gives them their due, and asks us to consider what might be productive about nursing a broken heart.

***

Franko B’s best-known piece is a performance entitled "I miss you," which he mounted in the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall in 2003. In it, he marches up and down a brilliantly lit catwalk, naked body painted head to toe in gleaming white, his veins opened up and leaking blood. As the performance progresses, the twin canvases of body and catwalk gradually run red. The whole thing is exhibitionistic, melodramatic and kind of tacky — just like the teenage girl who “accidentally” lets you see the fresh cuts on her arm while you try to eat your cafeteria lunch.

Unlike the cafeteria girl, Franko B gets away with “going there.” Maybe it’s because of his appearance — those teeth, those tattoos, that bulldog jowl. Even though his work is decidedly queer (with beautiful, dick-sucking boys making regular appearances), Franko B’s own physicality exudes a brutish, straight masculinity. It’s disarming to see a dude this coarse get so touchy-feely. As a man, Franko B’s expressions read as universal, rather than relegated to the ghetto of all that mushy girl stuff. But here’s the thing that I think Franko B, the cafeteria girl, and I all recognize: The aftermath of love is embarrassing.

I fell in love with someone recently. I probably shouldn’t talk about this either. My lover was tall and tender, with a rangy torso, jaggedy knees, and enormous hands that palmed me like a basketball. When it began, I told myself this-this-this was it. All the others who’d come before him were poseurs. Luv lite. And then, about a year in, it came to a screeching halt, with a spectacular shouting match in a park. Well, I did most of the shouting.

After my lover and I broke up, I did a lot of public crying. My favorite place to cry was on the New York City subway. It’d come over me like a bad meal — oh shit — and with nowhere to go, I’d just sit back and let the tears come. Sometimes I’d hold my hand over my mouth, in the hopes that this gesture might shield me from view. Sometimes I’d look to see who was looking at me. Sometimes I’d measure the tears so they’d trickle delicately over my cheeks. I’d leave them there, like a well-earned war wound.

I wonder why I did this. I don’t know if I wanted these strangers to fuck off or touch me.

In this scab-picking state, dealing with others is dicey. Sometimes, they offer us comfort; all too often, they pull us down deeper into the muck. In his performances, Franko B sometimes confronts the audience as if issuing a challenge. He stands there, gazing steadily. Do you feel my loss? Do you pity me? Do you relate? Do you want to help? Do you want to look away? In these moments, he seems to be reminding us that we’d do best not to pine alone. In a painting from a series entitled I’ll help u with the pain, Franko B gives us a pair of crude stick figures holding hands. Animals provide company too. In his performance Because of love (2012), he digs up a pile of severed fox heads and holds them tenderly in his arms. A 2010 installation, Love in times of pain, fills a room with a menagerie of blackened animals, familiars of the grieving heart.

***

After my lover left, one of my familiars arrived in the shape Anne Carson’s long-form poem, “The Glass Essay.” The poem enacts the reckoning that accompanies every breakup. What the hell happened? What was I thinking? Our reactions are unexpected and virulent. Resentment simmers, then boils. (One of Franko B’s neons flashes with the doth-protest-too-much petulance of the scorned lover: “I exist despite you,” it reads.)

In love’s aftermath, our memories quicken and thicken. They surface, envelop, stop us in our tracks. Carson knows this:

Perhaps the hardest thing about losing a lover is

to watch the year repeat its days.

It is as if I could dip my hand downinto time and scoop up

blue and green lozenges of April heat

a year ago in another country.I can feel that other day running underneath this one

like an old videotape—here we go fast around the last corner

up the hill to his house, shadowsof limes and roses blowing in the car window

and music spraying from the radio and him

singing and touching my left hand to his lips.

Carson reminds me of the sudden lurch of memory (That meal! That fight! That smell!) that jostles every broken heart. In the work of getting over it — work that, unavoidably, takes time — the ticker-tape of the relationship replays itself ad nauseum. Inevitable as they may be, these backward glances must be managed, lest they get too unwieldy and overcome us. So we develop little rituals to tend the pain, we give the grief a structure in which to play itself out. The comforts we seek might seem strange, or even irrational.

I, for one, watched this video dozens of times.

Throughout his work, Franko B shuttles back and forth between wounding and healing. He bleeds, and he nurses. The red cross that’s tattooed on his body clues us in. It shows up everywhere. It’s stitched onto canvas, it’s affixed to a pair of bright white nurse booties, it’s emblazoned on his website. There are ambulances, too—a veritable fleet of them, zooming across paintings. His most recent performance, Because of love (2012), has several moments that are particularly therapeutic. At one point, he hauls a heavy medical table onto the stage, then lies on it, clutching a hot water bottle to his chest. Suddenly, he heaves himself off the table, landing on the floor beneath with a smack. He rolls under the table and curls into a fetal position. Then he hoists himself back on the table, and as soon as he’s restored, he heaves himself off again. And again. And again. It’s disconcerting, this kind of self-inflicted pain. But the more he does it, the more oddly soothing it becomes. It’s a gesture that enacts the strange affinities between suffering and recovery.

***

Franko B doesn’t just trade in breakups; he deals with love in all its stages. Falling in, being in, falling out — all are fair game (one neon gushes, “you make my heart go boom-boom”). If anything, his work reminds us that love always operates via a necessary dose of longing, loss, and fantasy. Love idealizes. Love is also about faith — or rather, it’s driven by it.

In her book Eros the Bittersweet, Anne Carson writes that when we fall in love, we feel “more ourselves” than ever before. We arrive at that truest understanding of self by elevating the loved one, by making him shine: “Greatest certainty is felt about the beloved as a necessary complement to you. Your powers of imagination connive at this vision, calling up possibilities from beyond the actual.” In the beginning, my lover and I were perfect. A “gust of godliness,” as Carson puts it, passed through us both. The world existed in superlatives.

We frequently express this initial phase of love in terms of understanding. In a world full of strangers, haters and phonies, there appears a person who finally, thank Christ, “gets” it. It’s a heady thing, to be gotten. But here’s the thing about “getting.” To “get” implies catching someone up, possessing him, holding him prisoner in our own need for understanding. The problem, Carson tells us, is that understanding actually destroys the desire that fuels our love in the first place, for “That which is known, attained, possessed, cannot be an object of desire.” The paradox is that, while love makes us think that we can finally rest easy, in actuality romantic desire reasserts the edge of the self, that unbridgeable, interstitial space between us. To love, then, is to indulge in an impossibility.

A few months ago, I spent several hours falling in love with Franko B via his website. I told myself, I think I get it. I decided I wanted to write this essay as a kind of love letter, in the hopes that Franko B might read it and say, “yes. This is the text I’ve been waiting for all my life.” Flush with excitement, I emailed my lover. I wrote:

franko b inspires me to think about love. about being bound, about risk, about loss (of blood, of intimacy, of self), about wanting to connect and be intimate, but not always knowing how... i don't know if you will like his work, or be interested in it, but i am...

and this is part of intimacy... daring to share what we love with the one we love... so i share it with you.

He didn’t respond as I expected him to. He wrote:

yes please share and explain why this inspires you... IT IS MOST DEFINITELY NOT obvious to me in the least bit...

I don’t think he got Franko B. I certainly don’t think that he loved him.

This is why I love Franko B. Because he reminds me that love is as much about misunderstanding as connection. That I can miss you, even when you are standing in front of me. Even when you are in my bed. Even when you are making me dinner, or listening to me go on about an artist I admire. I may bleed out, but if I do, it’ll be for a good cause.