In January, I waited outside the Grand Palais in Paris for two hours in near-freezing temperatures to see a Claude Monet show, the first in nearly two decades in France.

As it was for everyone I knew who went to the show, waiting for Monet was part of the experience of seeing Monet. Three lines fed into the lobby entrance, elevated above the crowd by a marble staircase. I was in the line for people without reserved tickets, and, every so often, the guards would let a dozen or so of us in. It moved at a hand- and foot-numbing pace. After 30 or 40 minutes, the couple in front of me gave up. I started wondering why I was standing in the cold, waiting for art.

After a while, a group of patrons near the front started shouting, “À nous! À nous!” (“Now us! Now us!”) It was a defiant attempt to get the guards to open the line again. And often, it worked. At one point, a middle-aged woman in a purple jacket who had just made it up the marble stairs stood on the balcony, arms outstretched, and started to chant, “À nous! À nous!” encouraging us all to join in. “Bon courage!” she shouted, making a fist and shaking it in the air. It felt like a political rally, as sometimes happens in Paris, when a casual incident takes on an energy akin to a revolution in the making. But all I wanted was to get out of the cold and gray and see Impressionist paintings.

Inside, there were no chants but instead a shoving match. My feet numb and tingling, I pushed through pockets of German tourists, old Parisians anchored to cushioned benches, and American college students, looking for a comfortable place to see the canvases. But the crowds were too strong; people were pushing this way and that, handbags jabbing my arm or my back, sometimes rudely. I was too exhausted from the two-hour wait to try to see Monet. If the wait felt like a political rally, the exhibition felt like the revolution’s aftermath, and we all wandered around thinking that there must be more to this, that the wait in the cold should have led to something less chaotic.

Outside the museum, the newspapers and magazines at the kiosk were filled with news of protests and revolution in Tunisia. The protests began in December when in the small city of Sidi Bouzid an unemployed, university-educated man named Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire after police confiscated his fruit stand, which was his only source of income. Days of protests followed, and then another man from the same city climbed an electrical pole and reportedly shouted, “No for misery, no for unemployment,” and grabbed the wires, electrocuting himself. By January, protests against the Tunisian president had spread across the country. Looking at the headlines, my mind echoed with the chants of à nous! à nous!

Six months later, I remembered that cold January day as I waited in line to seeManet: The Inventor of the Modern at the Musée d’Orsay. I thought Manet’s work would be more appropriate to chants and protests, for threats of charging the guards at the curtained doorway, but this line was much calmer. Then again, we weren’t freezing in the damp Paris winter.

“Inventor of the Modern” was a big title to live up to, and critics were not kind to the show. Michael Kimmelman complained in the New York Times, “I can’t recall a major retrospective more clumsily devised. It’s a loveless exercise in curatorial pedantry, occupying a maze of cramped galleries larded with works by second-rank figures.” Julian Barnes noted in the Guardian that the show demonstrated “what a restless, as well as what an uneven, painter Manet was.”

If the artist was the inventor of the modern, I wondered what was the nature of this modern? Manet was constantly rejected by the salon judges and was rarely accepted by the critics of his day. Partly this was because he created canvases that shocked his contemporaries with overtly sexual subject matter. His famousLuncheon on the Grass (1863) depicts a nude female who smiles at the viewer as she sits casually with ordinary (and clothed) Parisian men. His bold Olympia(1863) confronts us with a courtesan lounging naked in her boudoir, gazing directly at us as if to invite us to keep looking.

But his work also unsettled critics because he created canvases that focused on everyday moments of Parisian life, played out in parks and concert halls, in the dance halls of Montmartre or in cafés. For example, The Waitress (1879) is a simple but striking canvas that captures a moment in a dance hall. The perspective is from behind the spectators looking toward a stage. We don’t know what is on stage really, for all Manet gives us is just the hint of a woman’s body in a white dress illuminated by stage lighting. What we focus on is the standing waitress, between a man smoking a pipe in front of her and a man wearing a top hat behind her. She is turned and staring at us.

The canvas raises questions about itself, the scene, and the true center of the painting. The best of Manet’s paintings work at this play on seeing and not seeing. But in our post-post art world of contemporary shock it is hard to grasp how a painter like Manet was revolutionary. To our more conditioned eyes, this painting—cropped and arranged more like a photograph—may not look so innovative or threatening. If Manet was the “inventor” of the modern, he was also the destroyer of art’s past, the rebel of tradition, and the creator of new ways of seeing.

As radical as his canvases were, we often forget that Manet’s creativity was deeply shadowed by a bloody siege of Paris and the subsequent violent social protests that followed. Throughout the winter of 1871, Prussians troops bombarded and blockaded Paris, destroying large parts of the city and plunging its citizens into starvation. During this period, as historian Mary McAuliffe relates in Dawn of the Belle Époque, most of the city’s trees were chopped down for firewood, and residents became more creative with French cuisine, making do with rat pâtés or dishes of antelope, bear, and stag, courtesy of the zoo in the Jardin des Plantes.

By the spring, after the Prussians had relented and the French agreed to a surrender, the postwar chaos provoked protests by those who suffered the most—the poor and working class. Their revolt against the blunders of the Second Empire and the policies of the conservative government that followed led to the Paris Commune and its bloody denouement. The Communards built a bastion on the hills of Montmartre, hauling dozens of cannons up the narrow streets to resist government forces. The ensuing violence destroyed more of the city, leaving large swaths a burned-out ruin. It ended in late May 1871, when thousands of Communards were executed in a standoff in Père Lachaise Cemetery. Hundreds of others were imprisoned or sent into exile on the South Pacific island of New Caledonia. Manet was deeply affected by these events. While he escaped the city before the siege and Commune, he was an ardent supporter of a liberal, democratic France. To consider this inventor of the modern, we also need to understand the violence and social protests that haunt his work.

* * *

In the Musée d’Orsay bookshop, among coffee mugs and calendars, I came across a recently published lecture Michel Foucault gave in Tunis in the spring of 1971 entitled “Manet and the Object of Painting.” In it Foucault argues that what “Manet made possible was all the painting after Impressionism, is all the painting in the 20th century.” Painting before Manet, so goes Foucault’s argument, was intent on tricking us with images that were meant to be true to life—engaging us with the pleasures of illusion and perspective. The canvas, in this tradition, was more a window than a flat surface. But Manet “ruptures” this illusion and confronts us with distortions and encounters that make us aware that we are looking at a canvas, at paint, and at a reality completely constructed and fabricated in two dimensions.

Take Foucault’s comments on Saint–Lazare Station (1872-3), which presents a woman seated along the fence of the station, dressed in a blue coat and holding an open book and a small sleeping dog. She stares directly at us, her torso bent a bit forward as if trying to catch our attention. Next to her, a girl of maybe nine or 10 stands with her back toward us, her left hand embracing the metal bar of the fence. Beyond her we glimpse the steam of the trains that abstracts and hides the entire scene the girl is looking at.

Foucault concludes his discussion of the painting, arguing:

It is this game of invisibility assured by the surface of the canvas which Manet sets in play inside the picture in a manner that, as you see, one could say is all the same vicious, malicious and cruel, since it is the first time painting has presented itself as something invisible that we watch. The gazes are there to indicate to us that there is something to see, something that is by definition, and by the very nature of the canvas, necessarily invisible.

The pleasures of Foucault’s interpretations are that they make us realize how the art transfixes the viewer. What is so dramatic and revolutionary about Manet’s canvases is that they make us aware of ourselves looking.

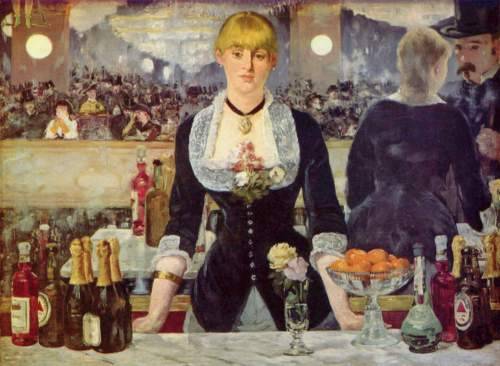

In the last part of the lecture, Foucault draws together his claims about the technical qualities of Manet’s canvases through an interpretation of the famous A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1881-2). The painting depicts a young woman standing in front of a marble bar staring at the viewer; behind her a large mirror illuminates a crowd we can only see in a hazy reflection. Just to the side of the mirror we see a well-dressed man facing the woman, but we see him only in the reflection. Clearly he should be in the way of our view of the woman, but he is not, and the experience of looking at the painting begins to be distorted.

This optical confusion between image and reflection illuminates the best of Manet’s revolution. “Manet did not invent nonrepresentational painting because everything in Manet is representative,” Foucault concluded his lecture, “but he made a representational play on the fundamental material elements of the canvas. He was therefore inventing, if you like, the ‘picture-object,’ the ‘picture-painting.’”

If Manet invented the painting-object, he also invented a new viewer who is aware of herself looking at paint on a canvas—at an image constructed. What is more intriguing for me about Manet is that he invented the modern viewer.

I was intrigued as much by what Foucault was saying in this lecture as where he was saying it. Tunis in the early 1970s was struggling under an economic and political crisis. That led to student protests against the increasingly authoritative regime of President Habib Bourguiba, who, since independence from France in 1956, tried to create a secular state based on philosophical ideas he learned in his studies at the Sorbonne in Paris. Tunisia had lived with French ideas for decades. France had moved into the region in the 1870s after its defeat by the Prussians. Indeed, France’s expansion into Tunisia was a point of debate in the post-Commune politics of Paris, where the conservative government stressed the importance of establishing a stronger hold in North Africa. Defeated in its eastward expansion, France turned southward, building an empire that would slowly erode about 100 years after Manet began painting.

But there, in Tunis in 1971, the French philosopher was discussing the vertical and horizontal axis and use of light in Manet’s paintings, details that illuminate the way his paintings ruptured the traditions of Western art. While there is nothing overtly political in Foucault’s lecture, you quickly realize that everything in the lecture was about political and social consciousness—about a realization of our place in a world of illusions.

We often talk about revolutionary art as that which shocks, that which radically changes what art is or can be. But Manet’s revolutionary art does more to the viewer than to the form. We tend to forget that often revolutions depend on new ways of seeing all that has been made invisible, forcing us to rethink the realities around us. This is where revolutionary art and social protest intersect, in that space where what is visible turns into a façade, and a new reality can emerge. Invisibility can be a powerful force in politics and art. The Communards knew this. Manet knew this. And those two desperate young men in Sidi Bouzid in Tunisia in December 2010 knew this as well. À nous! À nous!